Hidden Christians

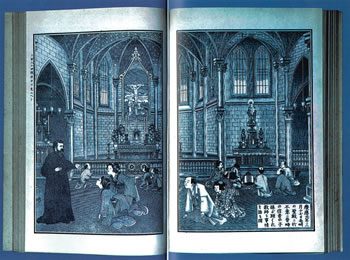

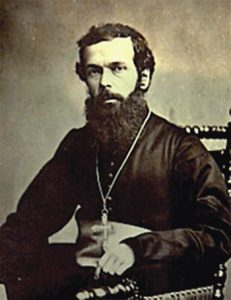

A picture, sent by Bishop Joseph Takami Mitsuaki,* shows the meeting, on Friday March 17, 1865, in the newly built church at Oura, of a group of clandestine Christians from the Urakami* valley (today part of the urban area of Nagasaki ) and the missionary Bernard Petitjean MEP (1829 – 1884). It’s hard to know how accurate it is – the engraving did not appear till 1925, in a re-edition of a book by Fr Aime Villion: The story of the Martyrs of Japan - not published in French. It illustrates, sixty years after the event, the story related to it, a story told many times over, and known by every Christian in Japan and beyond. When the engraving was published, the church had been altered more than fifty years earlier. It had been designed and built between February 1863 and December 1864.

A picture, sent by Bishop Joseph Takami Mitsuaki,* shows the meeting, on Friday March 17, 1865, in the newly built church at Oura, of a group of clandestine Christians from the Urakami* valley (today part of the urban area of Nagasaki ) and the missionary Bernard Petitjean MEP (1829 – 1884). It’s hard to know how accurate it is – the engraving did not appear till 1925, in a re-edition of a book by Fr Aime Villion: The story of the Martyrs of Japan - not published in French. It illustrates, sixty years after the event, the story related to it, a story told many times over, and known by every Christian in Japan and beyond. When the engraving was published, the church had been altered more than fifty years earlier. It had been designed and built between February 1863 and December 1864.

In January 1863 the missionary Louis Furet MEP (1816 – 1900) arrived in Nagasaki. He had to quickly find a place to house missionaries and build a church. The church would be a modest building, erected according to preconceived plans that were to be found in even the most distant Catholic missions at the time of their rapid development from the middle of the nineteenth century. Thanks to these plans, and making some changes according to the nature of the soil, the climate, the money available and the skills of the local workers, the building could be carried out at the least cost and time. Furet had chosen a piece of land overlooking the international concession and the harbour, he had started up a collection among the foreign residents, found patrons – one of whom was Eugenie, Empress of the French – her husband was Emperor Napoleon III.

Bernard Petitjean and Fr Joseph Laucaigne arrived in Nagasaki one after the other in 1864. Furet went away. The church was completed. It could be seen from a distance – a real attraction for the Japanese. They went up to it in groups, kids drew its outline on the ground. But was it all only to attract gawkers?

Bernard Petitjean and Fr Joseph Laucaigne arrived in Nagasaki one after the other in 1864. Furet went away. The church was completed. It could be seen from a distance – a real attraction for the Japanese. They went up to it in groups, kids drew its outline on the ground. But was it all only to attract gawkers?

The missionaries were expecting other visitors. Already they had identified the places related to the persecutions of 1587 and 1614, and even the sites of three churches, now disappeared. They were wondering if the persecuted Christians had any descendants. The ban on Christianity was still in force: here and there threatening notices could be seen, to remind people of the fact. At whom could they have been directed? The building of the church at Oura partly was to give a sign to any of those descendants. When the church was completed in 1864, the visits of the Japanese – no doubt warned by the police – stopped immediately.

The blessing and opening of the church, dedicated to the twenty-six martyrs of Nagasaki, on January 19, 1865, was quite an event.The church was filled with foreigners, a variety of uniforms, the event was saluted by cannon-shots in the harbour. But there were no crowds of Japanese: the officials who were invited had themselves been represented by underlings. The ceremony was fitting, but the missionaries were disappointed....

On March 17, 1865, shortly after midday, a little group of peasants stood near the closed doors of the church. Petitjean noticed them: their reserve, their reticence; they didn’t seem to be the usual sight-seers. The missionary made haste to join them, went ahead without saying a word, opened the church door, went in and left it open behind him. He went towards the altar, knelt down with a beating heart, perhaps these were the people so much hoped for? He asked God to give him words that would be appropriate. They stood behind him. Some women came and knelt beside him: one of them whispered in his ear: The hearts of all of us here are the same as yours.

According to Petitjean, the March 17th visitors numbered fourteen or fifteen, men, women and children. The picture has them in three groups. The most numerous are seven, kneeling in front of the altar of the Blessed Virgin and the statue. The artist has represented them as showing gratitude rather than as praying: “Oh, that’s right: that’s Maria-sama and that’s her divine son!” They are thinking of Christmas in seeing the Mother and the Child; they have preserved the use of the Christian calendar and observe the cycle of feasts which they celebrate secretly in their homes. But for these Christians deprived of the Eucharist for generations, the stature of Christ had been reduced to the proportions of a baby entrusted to its mother. Their devotion to Mary, guardian of a Child and of their hope, was really strong. The smallest group is in front of the main altar, the centre of the church. For these new-comers, this was the place most difficult to recognise: they didn’t know what it was used for. The return to the sacraments of which they had been deprived came progressively; it was only in 1866, at Christmas, that some dozens of them would make their first communion. Meanwhile, Bernard Petitjean became their bishop (in October). A third group, of four people, in the foreground of the picture (on the two sheets that make it up), has begun a conversation with Fr Petitjean. One of the women is turning around and making a gesture, perhaps to point out the ones behind her: The hearts of all of us here... The missionary is standing near the left edge of the picture, the witness, the necessary intermediary and in the foreground, so has stood aside to allow the Japanese to settle into their home, their church.

The visitors of March 17th 1865 had begun a movement of gratitude which would be sustained until June. Other Christians from the surrounding countryside and islands near Nagasaki came to see the church and the missionaries: “Some of them had come 20 or 30 leagues (80 or 120 km) in boats or on foot.” On some days, Petitjean and Laucaigne were overwhelmed, people crowded round them even into their house. They demanded that the missionaries remember their names. They asked for crosses and medals, and made them promise that they would soon return their visit.”They showed a confidence greatly different from the usual reserve of Japanese people.” This confidence, and that heart like theirs were the missionaries’ greatest discoveries of the Japanese soul.

On May 15th, speaking to the leader and the catechist of a group of visitors, the missionaries learned from them that the formula used for baptism was the same as theirs. These two men, for their part, made their own verifications of the identity of the missionaries: they wanted to know the name of the great leader of the kingdom of Rome. Petitjean named Pius IX and assured them that he would be happy to learn the good news that they would send... One further question was asked, with excuses: Do you not have any children? When the missionaries said that they were celibate, the visitors bowed to the ground and exclaimed “They are virgins! Thank you, thank you!” Prudence demanded the greatest discretion of the priests. The ban on Christianity being still in force, the Christians risked reprisals. Petitjean had heard of recent persecutions, in 1856. Eighty Christians had been arrested; about thirty of them had been imprisoned. Ten had died there, the others had been let go the next year, but eight had died shortly after, as a result of the bad treatment they had received.

In 1866 a newspaper published in the European concession revealed that Christians had been discovered. Inspection of a barque loaded with villagers showed that they had come from their island to Nagasaki to see the church: they were imprisoned to make them disclose exactly where they lived. In several villages Christians refused Buddhist funeral rites for their dead, ceremonies which up till then had been compulsory; they drew attention to their community and had to explain before the authorities.

During the night of July 14 -15, 1867, about sixty Christian were arrested. It was the beginning of a renewal of the persecution: imprisonment, rough treatment followed by exile, and confiscation of the exiles’ property.

The persecution would only end on March 31, 1873, with the edict of tolerance. Some of the exiles – not all- would come back to Nagasaki.

Footnotes:

*Bishop Mitsuaki - Archbishop of Nagasaki, an honorary member of the MEP.

* Urakami valley – later the site of the Urakami cathedral, destroyed in the atomic blast of August 9, 1945.

(Abbreviated) in “Missions Etrangeres de Paris,” April 2015

Translated by Fr Brian Quin sm.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)