Talking about spirituality today: 3

Spirituality and the Christian Message

1911 was a landmark in the spiritual tradition– certainly in the English speaking world. The Anglican writer and spiritual guide, Evelyn Underhill, published a significant book Mysticism: a study in the nature and development of Man’s spiritual consciousness. Since then, the study has gone through at least 12 editions.

Between 1911 and 1936 when Underhill published The Spiritual Life (originally four talks on the BBC), we can trace the shifts in her thought. This development highlights, for our purposes, FOUR foundational areas in spirituality and, here, Christian spirituality.

Foundations

First, the spiritual quest is not an escape from the world but a journey into the world where God is present and revealed.

Second, rather than a spiritual search for a pantheistic God identified with creation, the quest is built on the human need for a personal relationship with a personal God that leads to responsibility for the world.

Third, the spiritual quest is not just for the ‘mystic’ – a special person having special experiences – but for everyone. It is a journey for all humanity in the setting of ordinary life. Underhill moved from using ‘mysticism’ to the term ‘spiritual life.’

Finally (and most importantly), the spiritual quest does not reach its goal by the inevitable movement of the evolutionary process. It is not a human achievement. It is less our search for God and more God’s search for us. It starts with the divine gift of love, with God’s grace embodied in Jesus, rather than ends with it. It is a journey of being transformed by the divine Other in love.

Perhaps the key insight of Underhill is this – and this is central in this series. If mysticism is understood as personally engaging the divine mystery, then it cannot be separated from moral responsibility. The experience of the love of God (God for us, us for God) entails both a personal response and personal responsibility – to God, to others, to our world.

What, then, can we say about the divine mystery as the foundation of Christian spirituality?

What is the core of Christian Spirituality?

It is the person of Jesus Christ who embodies God’s answer to the human thirst for meaning and happiness. Jesus is God’s Word spoken from the depths of the divine silence.

Jesus is the definitive revelation of God and the definitive human response to God. He embodies in his humanity, as Paul says, the “fullness of the divinity” and calls us to share the life of the Trinity through him.

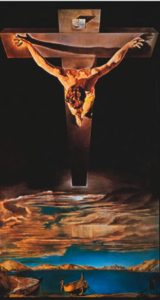

Jesus is the gift of God’s Shalom – the peace and harmony of being in right relationships – with God, self, others and the world/creation. It is in the crucified and risen Lord that we are transformed by love. What does God’s Word have to offer on this?

Jesus in the Gospels uses many images and metaphors to tell us about himself and the inner life of God. One image is particularly appropriate for Christian Spirituality. It is summed up here:

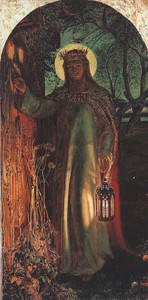

“Look, I am standing at the door knocking. If one of you hears me calling and opens the door, I will come in to share his meal, side by side with him” Revelation. 3: 20-23).

It is the divine offer of friendship. But this depends on our willingness to respond. Love cannot be forced. It can only be freely given and freely received. Holman Hunt’s famous painting captures this. There is no handle on the outside of the door.

Let’s probe this further in the Scriptures.

A God faithful to Promises

In the discourse between Jesus and the Pharisees in John 8, the Pharisees’ central question is ‘Who are you?’(8:25). Jesus responds by saying, in various ways, that everything he is as Son is from the Father –‘what the Father has taught me is what I preach’ (8:28). The climax of his reply provokes the ire of his listeners. They pick up stones to stone him for blasphemy.

‘I tell you most solemnly, before Abraham ever was, I Am.’ (John 8:58).

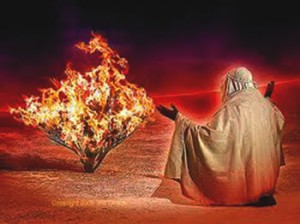

Clearly, the Pharisees did not miss the allusion. ‘I Am’ is the Ego Emi used in the response to Moses’ question ‘but if they ask me what his (God’s) name is, what am I to tell them?’ The Lord God’s reply is that ‘I Am has sent you.’

This is made more specific – this is the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. This is the God who has always been there, present in the events and history of their lives. The God revealed to Moses is discerned in action, in being there for and with his people.

The Jesuit theologian, John Courtenay Murray (significant in drafting the Declaration on Religions Freedom of Vatican II), once suggested that Ego Emi could be translated as ‘I shall be there as who I am shall be there.’ This is the God of the Covenant – who will always be here for us, who is always faithful, who has carved our names on the palm of His hand.

The Jesuit theologian, John Courtenay Murray (significant in drafting the Declaration on Religions Freedom of Vatican II), once suggested that Ego Emi could be translated as ‘I shall be there as who I am shall be there.’ This is the God of the Covenant – who will always be here for us, who is always faithful, who has carved our names on the palm of His hand.

God of the Promises at Work

We are helped here by Pope Benedict XVI in his Jesus of Nazareth. “Humankind, in every age, tries to answer the question of our origins – where do we come from? But more important is the preoccupation with the hidden future – where are we going? Why are we here? All religions and cultures display the yearning to tear away the curtain, to lift the veil of the future, to penetrate mystery (my = ‘hidden’ in Sanskrit). Deuteronomy 18:9-12, through Moses, speaks of different methods used by cultures surrounding Israel to open a window on, and seize control of, the future – through human sacrifice, divination, soothsaying, sorcery, wizardry, mediums. Such methods are an ‘abomination to the Lord.’

By contrast, as Benedict points out, the way of Israel is that of faith, one that takes the form of a promise.

Yahweh your God will raise up a prophet like myself from among you…to him you must listen.’(18:15).

At first sight, this appears to indicate a prophetic office that will interpret present and future. But experience showed that this lapsed into the false forms of prophecy at odds with the way of faith.

At the conclusion of Deuteronomy (34:10) the form of this promise is made clearer. In pointing to a new Moses it takes a surprising twist, one which gives the role of the prophet its true meaning.

Since then, never has there been a prophet in Israel like Moses- the man Yahweh knew face to face.

Moses is so important since his ‘unique and essential quality’ as a prophet was that he conversed with God ‘as a man speaks with his friend’ (Exodus 33:11). This is the way of faith concerning the future and the veil of mystery.

The distinguishing aspect of the new Moses will be a face-to-face relationship with God through which God’s ‘will and word’ are communicated ‘firsthand and unadulterated.’ That is how we are called to walk towards the future - ‘the saving intervention which Israel – indeed the whole of humanity- is waiting for.’

Jesus, as the New Moses, sees himself precisely in these terms.

‘No one has ever seen God: it is the only Son, who is nearest to the Father’s heart, who has made him known’ (John 1: 18).

And this immediate and personal relationship is something to be shared with us.

‘I call you friends because I have made known to you everything I have learnt from my Father’ (John 15:15).

And so?

What is spirituality in relation to the Christian mystery?

It is a deepening friendship – with the Father, through the Son, in the Spirit. The spiritual quest is one driven by God’s gift of himself, the desire to make a ‘home’ in us. Jesus wants to ‘share his joy…to the full’ (John 17: 13) and exhorts us to ask and you shall receive so that your joy may be complete’ (John 16: 24).

If God wants to take up a dwelling place in us, it is as three persons – the Trinity of Father, Son and Spirit. That will be the concern of the next article.

Next Month:

Christian Spirituality and the Trinity.

Sources:

Michael Downey, Understanding Christian Spirituality

Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth Vol. 1.

Tagged as: Christian Message, Christian Spirituality, Evelyn Underhill, John Courtenay Murray sj, joy, spirituality

Comments are closed.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)