Talking about Spirituality Today: What’s Happening

1.‘Spiritual but not religious’? - What’s happening?

In 1997, Michael Downey cites a USA Gallup survey. It forecast that between 1987 and 2010, the largest sales in non-fiction books would be in the category of religion and spirituality. In 2003 in Australia, David Tacey spoke of the ‘spirituality revolution.’ He sees this as a movement of the ‘spirit’, a concern for health and well- being in a society that is ‘running on empty.’

If we go into a mainstream bookshop, we will certainly find a section with ‘Spiritualty’ or perhaps ‘Wellness.’ Titles will reflect concerns such as ‘exploring the New Age’, ‘finding the inner self’, ‘the power of crystals and numbers’, ‘meditation and health’ or ‘ naturopathy and well-being’, ‘Gaia and the power of the universe.’

It would be unusual if the word ‘God’ appears, let alone Jesus. Some aspects may seem odd, even bizarre, to be called ‘spirituality.’ Some trends and practices give cause to hope, some for caution.

But can they be easily dismissed? What is it all saying?

Symptoms of a Thirst

Downey points out that these are symptoms of spiritual thirst and hunger. They reflect the enduring restlessness in the human spirit, a desire of something more. When these deepest yearnings are ignored, they can take extreme, even bizarre forms. As the old adage goes, ‘nature abhors a vacuum.’

They become more urgent in times of crisis, of pain, loss, death. Even with the widespread decline in Church attendance and Christian allegiance, at such moments recourse to Christian ritual, language and symbols is often the ‘default’ position. This was apparent in the aftermath of the death of Princess Diana. It was also the case more recently with the earthquakes in Christchurch, floods in Queensland and the fires in Victoria. Again, a generation ago, who would have thought that the British College of Psychiatrists today would have a link in its website ‘Spirituality.’?

Four Themes

Downey cites Editor Phyllis Tickle’s four valuable insights into the growing literature on ‘spirituality’ that can be instructive about trends beyond North America.

First, people believe in the sacred and that it is possible to come into contact with it. Further, that the sacred is searching for us, trying the make contact. This is evident in the writings on near-death experiences, angels, miracles and prophecies.

Second, there is a search for ways of wisdom that have been tested by time and human experience. It is a return to tap the sources of the past, as in the spiritual heritage of the East. There is a growing appreciation of indigenous religious traditions concerning, for instance, of the centrality of the land for Aboriginal peoples in Australia and Maori in New Zealand.

Third, there is the belief that people must take responsibility for their lives. This is evident in the range of self-help movements modelled on the twelve steps of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Fourth, there is the appeal of stories offering plain, straightforward messages. This may take the form of TV ‘soapies’, human interest programmes, searching for family roots. Or it may be stories such as Joseph Girzone’s Joshua.

A Fifth Theme?

But perhaps there is a fifth theme that could be added here. It is captured in a commonly- heard phrase - “I’m spiritual but not religious.’”

This is no doubt as to why so many people are increasingly disillusioned with, even angry towards, all institutions whether political or governmental. Churches (including the Catholic Church) are certainly no exception.

Perhaps it also highlights some value in the distinctions implied by Tickle. ‘Spirituality’ is more subjective, centred on a personal attitude and choices about the sacred. ‘Religion’ is objective, less personal and offers a framework from a wider tradition for find meaning in life and of the world. Blending them together is the ‘sacred’ – common to all men and women, a ‘given’, part of the very structure of our being.

However we understand these words, Downey sums up a ‘tidal wave of interest’ in spirituality where people ‘…seem to be grappling with the deepest yearnings of the human heart, a desire for more than meets the eye- for the sacred.’

Hard-wired for the sacred

Tickle’s comments converge with the research projects initiated in the United Kingdom in the 1950s by the biologist Alistair Hardy. These surveys confirm the experience of ‘a power beyond oneself (whether they called it God or not)’ amongst thousands of ordinary ‘non-religious’ people.

Later, extensive work was conducted on the spiritual development of children by David Hay and Rebecca Nye. Hay’s most recent study is on the biological roots of human spiritualty (Something There: The Biology of the Human Spirit).

In 2011 in the USA, Robert Bellah completed an extensive study of the biological foundations of the religious sense in human beings in Religion and Human Evolution. Despite today’s protests of Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens and the atheists’ conventions, these and other scientific studies confirm that human beings are ‘hard-wired’ towards the sacred - to be spiritual and religious beings.

Why This Surge in ‘spirituality’?

There seem to be a number of factors at work. Perhaps most important is the experience of the 20th century and the horror of evil. It is estimated at least 100 million people died as the result of wars, genocide, the Shoah and social / economic ‘engineering’ (as in China, and Russia). This led to questions about God’s silence in the face of such malevolent and destructive human agency.

This aggravated the distrust of ‘meta-narratives’ or all- embracing, universal explanations of life and the world. This extended to the institutions associated with them – for instance Churches and political systems such as Communism. More broadly, there is disaffection with traditions from the past. There is also the impact of the Twin Towers of 9/11 and rise of Fundamentalisms.

In a world where people have lost their moorings, how does one make sense of life? People are thrown back more on their own resources. There emerges an understandable concern for self and personal health and well-being. This is combined with the desire to choose from a smorgasbord of offerings in shaping a personal ‘spirituality.’ The measure is ‘does it make me happy?’ or ‘does it work for me?’

In recent times, there are the effects of Internet and the increasing role of social networks and phenomena such as Facebook. While there is connection, is there the mutuality and vulnerability of relationships with human beings who are flesh and blood?

Final Considerations

We are mainly talking about the western developed world. We have to keep in mind the global picture. There is the growth of Christianity in China. There is the rapid expanse of Pentecostal Churches on the African continent and in Latin America. The centre of gravity of Christianity is moving ‘south.’ For instance, on present figures, by 2050, the number of Christians in Africa will double to over a billion.

Second, we should be careful of understanding ‘spirituality’ too narrowly. God’s Spirit can work in many ways. Consider the extraordinary response of ordinary people to the needs of others (often complete strangers) in the natural disasters in Christchurch, Japan, Queensland and Victoria in recent years. The concern, even love, was so apparent. The words of Matthew’s Gospel quickly come to mind - ‘whenever you did this to the least of my brothers (and sisters) you did it to me.’

Finally, when we consider the New Age phenomenon and its impact on young people, it is worth keeping in mind this story.

In a recent CathBlog, journalist Elizabeth McKenzie writes of a conversation with a young mother who, with her husband, were ‘cradle-catholics.’ They were raised in practising households, educated in Catholic schools.But for this young woman, while ‘The Church’ is totally irrelevant, spirituality ranks high on her list of priorities.

She has discovered the modern New Thought movement and writers such a Deepak Chopra. McKenzie sums it up.

She finds the themes of the movement – the presence of an infinite cosmic Divinity, the universality of spirituality, that there is a divinity inherent in each individual, the emphasis on positive thinking – very attractive. In the past, she was drawn to Buddhism, so she also likes the acceptance of other faiths’ prophets and teachings, and the emphasis on prayer and contemplation.

‘What’s not to like?’ asks McKenzie.

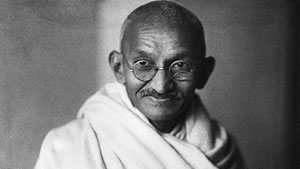

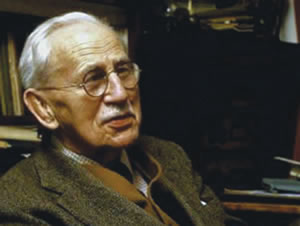

One of the positives for my young mum of these teachings is that it is totally OK to accept Jesus. Not just as a respected but also as a revered prophet in a pantheon of prophets from Moses to Gandhi (including Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Mother Teresa.) For her, this is very comforting. Her religious gripe is with the institutional Church, not with the teachings and influence of Jesus.

One of the positives for my young mum of these teachings is that it is totally OK to accept Jesus. Not just as a respected but also as a revered prophet in a pantheon of prophets from Moses to Gandhi (including Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Mother Teresa.) For her, this is very comforting. Her religious gripe is with the institutional Church, not with the teachings and influence of Jesus.

Perhaps this wise advice helps keep things in perspective. It also points to the next article in this series.

Next Month: What do we mean by ‘Spirituality’?

Sources: Michael Downey, Understanding Christian Spirituality

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)