The Beginnings of the Catholic Church in Tonga

Based on the writings of Fr Joseph Deihl SM, adapted by Fr Kevin Head SM

Part 4

Fake News!

Towards the end of 1851 and in early 1852, rumours circulated in Tonga about the downfall of the monarchy in France. In fact, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, later Napoleon III, had staged a coup d'état on 2 December 1851 so that he could remain in power. The monarchy had fallen as long ago as 1793, with the execution of Louis XVI. Rumour had it that the king of France and the pope had fled to England, had become Protestants, and that Catholicism survived now only on small islands like Wallis and Futuna!

Such rumours did great damage to the prestige of the Catholic missionaries, and the situation of Catholics in Tonga became increasingly testing and hazardous. Fr Deihl wrote, “the followers of Methodism, becoming unconstrained, in many places brought pressure upon Catholics to renounce their religion.”

The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries,

by Jacques-Louis David, 1812

Frs Chevron and Calinon attempted without success to trace the sources of the fake news, as they realised that the ill-feeling between the religions could easily lead to war. They spoke with the Methodist missionaries and with King George Tupou in an effort to bring about better relations with them. The fact of the matter was that it suited the king to encourage anti-Catholic sentiment so that he could justify himself when the time came to go to war.

At the beginning of 1852, a forged document stated that a high chief from Pea and Fr Calinon had written to the French government to invade Tonga. King George had “perpetrated the forgery - it was the wanted spark to light.”

The Fires of War

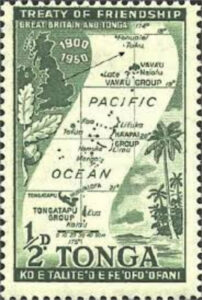

War drums sounded on the night of 1 March 1852. The Methodists went to King George Tupou’s headquarters in Nukualofa; the Catholics, along with those of no religious affiliation, fled to the fortified villages of Pea and Houma, where they were able to withstand the attacks of the Protestant forces which had been reinforced with warriors from Ha’apai and Vava’u.

Having arrived again in Tonga, Bishop Bataillon tried to meet with Tupou to plead for peace, but Tupou wanted war and intensified his assault on Pea, the Catholic stronghold. According to the rumour mill, the bishop had brought weapons for the Catholics, and had sailed off to ask France for protection.

The situation was so desperate that Fr Calinon, along with Frs Charles Nivelleau (1823-1852) and Louis Piéplu (1818-1857), who had arrived in Tonga in 1841, asked Fr Chevron to appeal for help from the French navy in Tahiti. Fr Calinon set out for Tahiti on 17 June. His efforts bore no fruit.

The village of Houma surrendered in July, and the villagers saved their lives by giving up their faith. Pea, “the cradle of Catholicism and the bulwark of its progress,” also fell, after resisting the attacks of its enemies for fifty years. Fr Chevron wrote, “May the Lord be blessed! In the midst of tribulation, we are neither less calm nor less content than if everything had succeeded according to our desires: is it not the will of God?”

British Interference

British Interference

Fr Deihl wrote, “In 1852, with George Tupou riding high in the saddle, the recognised master of Ha’apai and Vava’u, … it was quite possible for a passing observer to confound issues and to see only rebellion at Pea and to adjudge the Catholic priests who laboured there the arch supporters of that rebellion. Captain Home of H.M.S. Calliope reached Tonga in August of that year. The interest of humanity demanded of him that he take some step to bring peace to distraught Tonga, but in a very curt interview with Father Chevron he left no doubt as to his political views and his intended line of action; he was astonished that two missionaries (Father Piéplu and Father Nivelleau) encouraged rebellion at Pea by their presence; he would write to them to leave at once for he was prepared, by all possible means, to aid George Tupou to remove this hot bed of civil war.

No one realised more than the two Fathers how fraught with personal danger was their position at Pea (Father Piéplu had only the day before been wounded) 1 and yet they elected to reply to Captain Home through Father Chevron that it would be unworthy of their character as Catholic priests to desert their posts when so many of their faithful were exposed to danger and they reminded Captain Home that even were it granted that the Peans were rebels, yet were there many women, children and sick who demanded their care.

HMS Calliope

Uncivil as he had been at the first interview, Captain Home could not hide his admiration, and together with his officers, he cordially shook hands with Father Chevron. Basil Thompson remarks, “the courage they showed in braving the dangers of a siege by a stronger party with the prospects of a savage victory at the close, compares favourably with the conduct of their rivals who fled the island in 1840 and deserves something better than the sneers that have been heaped upon them by the Wesleyan missionaries.”2

Captain Home attempted to bring about peace. On 18 August negotiations between the warring factions took place in Nukualofa. The next morning, warriors from Tupou’s forces approached Pea unarmed, calling out in friendly fashion to the defenders. The gates of Pea were opened to admit the visitors; and then, warriors from Vava’u came from the rear. Pea’s leaders were still in Nukualofa. Leaderless and outnumbered, the defenders fled.

Fr Deihl: “Pillage and destruction followed: Fr Nivelleau hastened to the church and consumed the Sacred Species to prevent profanation and then calmly sat himself on the chest in which were the chalices and sacred vestments, whence neither threats nor menaces could move him; Father Piéplu stood at the door of his dwelling, thus protecting two chiefs whose heads had been demanded, while before him milled the warriors of George, eager for blood and plunder. The news of the attack upon Pea soon reached Nukualofa, some four miles distant, and with all possible speed Captain Home and Tupou raced to the scene. The church of Pea was already in flames but under the command of Tupou what could be saved was snatched from the burning building.”

Fr Charles Nivelleau SM

Fr Philippe Calinon SM

Pea was no more

The village of Pea was completely destroyed. In a letter on 27 August, Fr Chevron wrote, “From that moment rosaries were snatched from the neophytes and broken in contempt, and the same was done with medals and crosses. Some of the faithful were struck with the butts of guns until they were unable to rise. To crown the work, all the people of Pea were dispersed or lead into slavery, especially those who were known for their attachment to the faith. Only those who are apostatised received any consideration. Many were deported either to Ha’apai or to Vava’u, where it was hoped far from our influence, their resistance would more easily be overcome” To quote again Basil Thompson, “Lavaka, Ma’afu and Tupouleva were pardoned and they forthwith renounced both heathenism and the Christianity of the Roman church, which the Protestant chronicler naively classes together. Thus ended the second Wesleyan crusade, and Protestantism, sustained by the musket and the club, was again triumphant”3.

Father Calinon’s efforts to secure protection from the French navy came to nothing.

Fr Piéplu was wounded in the stomach …Providence willed that two hedges and a wire screen stood in the bullet’s way.

The blow knocked him down but did not wound him. A sore then developed which prevents him from working. 1

Fr Deihl: “It is by such trials as these that God is wont, sometimes, to test the souls of his servants. Out of the wreckage and destruction of his ten years of labour Father Chevron calmly set himself to salvage the remnants.”

Pea was destroyed but Mua stood. Lavaka and other chiefs apostatised, but the Tui-tonga, baptised in 1851, remained faithful. It was at Mua that the Catholic religion flourished. Fr Deihl: “Mua became Catholicity’s capital, the residence of its missionaries and the centre whence radiated hope and a new life. One by one they returned, his weak children, who had cowered before the storm, to throw themselves at the feet of Fr Chevron and to declare unto him their readiness to suffer all the consequences of hate and persecution rather than apostatise a second time. The beautiful ceremonies of the Church and her feasts were celebrated with a greater solemnity and with more marked fervour than ever before. Through the years ahead, adult baptisms constantly increased and out and beyond at Ha’apai and Vava’u, exiles were awaiting and earnestly praying for the day when they too would be able to share in the fullness of joy of the new resurrection.”

Pea was destroyed but Mua stood. Lavaka and other chiefs apostatised, but the Tui-tonga, baptised in 1851, remained faithful. It was at Mua that the Catholic religion flourished. Fr Deihl: “Mua became Catholicity’s capital, the residence of its missionaries and the centre whence radiated hope and a new life. One by one they returned, his weak children, who had cowered before the storm, to throw themselves at the feet of Fr Chevron and to declare unto him their readiness to suffer all the consequences of hate and persecution rather than apostatise a second time. The beautiful ceremonies of the Church and her feasts were celebrated with a greater solemnity and with more marked fervour than ever before. Through the years ahead, adult baptisms constantly increased and out and beyond at Ha’apai and Vava’u, exiles were awaiting and earnestly praying for the day when they too would be able to share in the fullness of joy of the new resurrection.”

In January 1855, His Excellency M Du Bouzet, governor of the French colony of Tahiti, arrived in Tonga. An agreement between Tupou, king of the Tonga Islands and M Du Bouzet, in the name of His Majesty Napoleon III, was drawn up in the two languages and signed by Tupou and Du Bouzet on 9 January 1855.

Under Article II, the Catholic religion was declared free in all the islands under the king of Tonga and its members were to have all the privileges accorded to Protestants. Under Article III, all natives of the Tonga Islands banished and deprived of their property on account of religion, were to be at liberty to return to their homes and to have their lands restored to them.

In the very darkest times, Fr Chevron had written, “Let us hope that the Blessed Virgin will not abandon Tonga.” His confident trust in the Queen of Oceania was not misplaced.

[1] Letter of Fr Chevron to Fr Colin, Letters of French Catholic Missionaries in the Pacific 1836-1854 ed Fr C Girard SM

[2] “Diversions of a Prime Minister” page 358

[3] ibid page 360

Sources:

MM March, April 1934

Letters of French Catholic Missionaries in the Pacific 1836-1854, ed Fr C Girard SM

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)