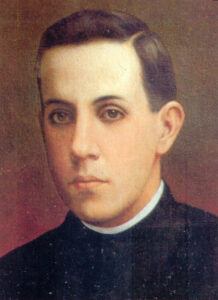

Blessed Miguel Pro SJ

By Tricia O’Donnell

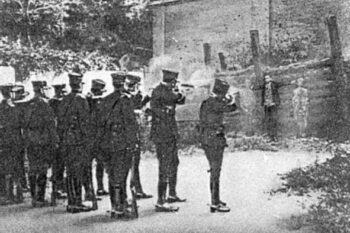

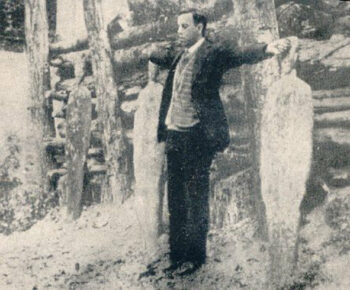

On the 23 November 1927, a young Mexican Jesuit priest stood before a firing squad. He was guilty of no crime, had faced no trial, but arms outstretched in cruciform, a rosary in one hand and a crucifix in the other, Padre Miguel Pro went to his death.

Mexico at the time was in the grip of a revolution which had begun decades earlier. Economic and industrial issues created instability and revolutionary movements, resulting in the 1924 election which brought to power President Plutarco Elias Calles. Viciously anti clerical and particularly anti Catholic, Calles ruled with an iron fist, doing everything in his power to undermine the Faith in a country predominantly Catholic. Anti-clerical laws had been building steadily over many years but Calles Law, as it became known, took it to a whole new level. Celebrating Mass in public was outlawed, priests were not allowed to wear their clerical dress in public, church property was confiscated and monasteries, convents and religious education centres closed. Imprisonment or worse awaited those who disobeyed.

This then, was the culmination of events that began in 1911 when the Mexican

Our Lady of Guadalupe

President Porfirio Diaz was ousted. That same year twenty-year-old Miguel Pro entered the Jesuit novitiate in Mexico. Miguel had been born to a devoutly Catholic family in Guadalupe. One of eleven children, four of whom had died in infancy, his parents were naturally distraught when he too succumbed to a serious illness while still very young. He was close to death for several days before recovering, but he remained far from well, appearing to have brain damage and suffering from convulsions. A year on, he was still seriously ill and was once again near death when his father held him before an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe and cried out, “Mother give me back my son!” Finally, he began to improve and his first words were to ask his mother for a ‘cocol,’ a sweet bread roll. From then on, he became known as Cocol to his family, a name which stayed with him throughout his life. It would not be the last time he would suffer serious ill-health.

Miguel’s childhood was a normal one. Though devoted to his Faith, he had a mischievous nature which often got him into trouble, and an ‘exquisite wit,’ according to one of his friends. That same friend said there were two Pros, the playful Pro and the prayerful Pro! He would need both his humour and his devotion for what he would have to go through in the years that followed.

Three years after joining the seminary, Miguel, along with all the other Jesuits, was forced into exile as anti-Catholicism raged through the country. After a brief spell in Texas and California, Miguel travelled to Spain, Nicaragua and finally completed his theological studies in Belgium, where he was ordained on 31 August 1925. He wrote later that he “could not hold back the tears on the day of my ordination, above all at the moment I pronounced, together with the bishop, the words of the consecration.”

A few months later, Miguel’s health began to fail and he underwent at least three operations. It is not clear what the illness was, but it is believed to be an abdominal one, possibly ulcers. The following year he arrived back in Mexico, in July 1926. The signs had been there when he’d been forced to flee twelve years earlier, but he could hardly have been prepared for the total radicalisation he encountered on his return.

The 1917 Constitution of Mexico had changed the political landscape dramatically and the years following had been an ongoing process of lessening the influence of the Catholic Church. Shortly after Miguel’s arrival, President Calles issued further restrictions and penalties for disobedience which forced the bishops to abandon efforts to maintain the churches that remained and encouraged priests to leave. Some states, Tabasco for instance, had already shut all their churches and banned priests from celebrating Mass. Many priests were killed, though some survived to celebrate ‘underground.’

"Long live Christ the King"

Miguel and other priests in his area of Mexico used the time before abandonment to hear confessions and perform baptisms and weddings. His frail health was a constant source of worry and it is said that he spent so much time hearing confessions that he would often faint and needed to be carried out. Eventually, the priests dispersed, though a few, including Miguel, continued to work in secret. He was arrested on one occasion, and although released the following day, was under the watchful eye of the authorities.

In the midst of the turbulence of these times in Mexico, there existed a militant group called the Cristeros – Soldiers of Christ – Christians who fought against the anti-Catholicism by targetting the politicians who made the rules. When an assassination attempt on the life of former President Alvaro Obregon failed, the government’s investigations discovered that Miguel’s two brothers, Roberto and Humberto, were members of the organisation, which was reason enough for the authorities to implicate the priest. All three were arrested and despite another member of the group swearing that the brothers were not involved, they were sentenced to death without a trial.

President Calles was determined to use these men as an example to other Cristeros of the consequences of further militancy by publishing photos of Miguel’s execution in newspapers throughout the country. The president’s efforts were counter-productive. Not only did his action give impetus to the rebels’ cause, but Calles must have been dismayed at the multitudes of mourners who came out to farewell their beloved padre. About 40,000 people lined the streets for his funeral procession and 20,000 stood at the cemetery as his father prayed for his son in the absence of a priest.

Miguel Pro was 36 when he died. Without bitterness, he blessed the soldiers, then knelt and prayed before standing, preparing to die. He refused a blindfold and spreading his arms cross-like, he cried out “Viva Cristo Rey” – “Long live Christ the King.” The firing squad failed to kill him. That was left to one of the soldiers, who shot him in the head as he lay on the ground.

On 25 September 1988, on beatifying Miguel Pro, Pope John Paul II said:

Neither suffering nor illness, nor the ministerial activity, frequently carried out in difficult and dangerous circumstances, could stifle the radiating and contagious joy which he brought to his life for Christ and which nothing could take away. Indeed, the deepest root of self-sacrificing surrender for the lowly was his passionate love for Jesus Christ and his ardent desire to be conformed to him, even to death.

His feast day is on 23 November. Blessed Miguel, pray for us.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)

Thanks for publishing this on Bl. Miguel Pro SJ

He is a great example for Priests and of not being afraid to speak and live the Truth of our Catholic Faith.

We may not have to live under the threat or a dictator like President Plutarco Elias Calles: but we

certainly face the dictatorship of an aggressive secularism which states in every way that there is no longer

room for God let alone Catholicism...! Society in general accepts this philosophy and (sadly,) so do many ex- Catholics. We are either unprepared and/ or don't know how to answer the questions when society and our young people ask about the existence of God, our Faith and just why we believe in this ''Bronze Age Mythology" in the 21st. Century!? In general, Catholicism has become very bland and the beauty and richness which the Council intended to amplify and showcase to the secular world, has not been realized, because of a poor reading of what the Council really was about. We need to reclaim and get serious about knowing the Truth in all its richness and colour which Catholicism is and then give it to the world in love and humility. We need to be evangelized as Catholics and then to evangelize.

Bl. Miguel Pro loved God passionately, knew his Faith and worked selflessly with good humour and humility. ''Viva Cristo Rey!" (Long live Christ the King!) were his last words. May he and his example light a fire in us, open our eyes, hearts and minds to be the saints we are individually called to be.