Marie Françoise Perroton

Part 2 of 2

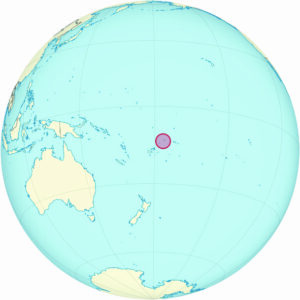

175 years ago, at the age of 49, Marie Françoise Perroton set out from Lyon to follow a missionary call to the Pacific. After a voyage of eleven months the ship finally arrived in Wallis.

Reception in Wallis

They were two days on board at Wallis before a suitable wind enabled the Arche d’Alliance to pass through the narrow reef opening to the lagoon.

The priests and brothers were given a very warm welcome. But, what deception! Marie Françoise Perroton “was received in a very cold manner,” wrote the resident priest, Father François Junillon. Bishop Bataillon, who together with Father Viard had co-signed the letter from the Christians in Wallis requesting women to come, refused to allow Marie Françoise to leave the ship to be an ‘auxiliary’ in the mission. Was it because he did not want to add fuel to the hostile gossip of the Protestants of nearby islands by having a European woman who was single on the mission station?

The King, Lavelua, however, readily welcomed Marie Françoise. He took her under his protection and gave several young girls, including his daughter, to be her companions. A hut by the sea was built for them in Matautu.

Two months later the Bishop would write that “Mademoiselle Perroton seems to have what it takes to succeed.”

Challenges were many. Among them, adaptation to the food, climate, the island way of life, and the language, which she never really mastered. Marie Françoise taught catechism, prayed with the girls, and made use of her sewing skills. She trained the girls to take care of the church, how to sew and iron, and how to write.

By 1850 she was teaching about 100 girls. In spite of all these young lively companions, this generous woman admitted the dreariness she felt in living alone: Will I tell you ... all the suffering my isolation causes me? I am resigned to God's will, but I would prefer that his will was more in accordance with my own. Although she longed for some European companions, she did not want anybody to join her unless the circumstances were different.

Although the priests appreciated the contribution she was making; they also felt for her because of her solitude. Occasionally there would be visitors: the mission boat on its rounds, American whaling boats in the lagoon, French naval battleships, and priests and some Catholics from Rotuma who had to flee their island because of harassment by the Protestants.

Marie Françoise reached the point when she felt she could no longer continue. With Bishop Bataillon, Fr Junillon, and two of her girls she left on a ship heading for Sydney.

Futuna

During a stop-over in Futuna, Marie Françoise visited Poi where Peter Chanel had been killed thirteen years previously. Without informing the passengers, the ship departed. So the Bishop sent her to Kolopelu, a rocky plateau above the coast, where Marie Françoise settled down. She considered this “most charming site - a real earthly paradise”... even if water had to be carried up the steep path from the coast! The language, different from Wallisian, continued to be a challenge.

Concerned for her morale in the lonely situation, after several years, one of the priests wrote that the time had come to send religious women from France to these islands that had been converted.

Then – what a surprise! One evening the Marist mission procurator, Fr Victor Poupinel, and three women arrived, accompanied by numerous Futunians, guiding them with flaming torches along the hazardous slippery path. Marie Françoise did not know what was uppermost in her feelings. She wrote to the Superior General of the Society of Mary, Fr Julien Favre: joy, surprise, or gratitude to God, the Blessed Virgin and you, Reverend Father, who have had pity on my isolation.

The Missionary Sisters of the Society of Mary consider these four women as the first community of our eleven pioneer sisters.

Next morning, 31 May 1858, this sixty-two-year-old was received as a novice in the Third Order of Mary for the Missions of Oceania. She took the name of Sister Marie du Mont Carmel.

To Fr Favre, Marie Françoise wrote her song of praise:

Blessed be God, blessed be our Immaculate Mother who have inspired you to send me help, or rather successors, and at the same time supply Sisters of the Third Order for several other parts of the vicariate. May they multiply and produce all the fruit that your paternal zeal expects from them. I am happy and proud to have launched the movement; my thirteen years of trial will be counted among the best times of my life. I would never have dared to hope for such happiness for I had resigned myself to die here alone; and now the good Lord has willed that I become a Tertiary of Mary, notwithstanding my unworthiness.

Marie Françoise’s work continued along the same lines as in Wallis, but now she had others to help her – well, for three months anyway. Wallis was crying out for sisters, so in August 1858 the Bishop sent two of her companions there.

Always struggling for resources to run the mission, Bishop Bataillon soon closed the school in Wallis run by the Sisters. He wanted them to make the mission farm productive. Two or three times he broached this possibility for Futuna with Marie Françoise. She wrote: ... as you may well imagine, the tough old Sister du Mont Carmel was far from weakening on the aims she proposed to herself when she left her country; poultry, cows or pigs never entered into her plans and will never do so, except as a sideline or to fill some urgent need. ... I was absolutely astounded at this proposal.

Throughout the next 15 years until her death in 1873, Marie Françoise was often alone on the rock of Kolopelu with some girls. Occasionally she had a Sister companion. But her compelling missionary vision remained, sustained by her certainty that she was where God wanted her.

Throughout the next 15 years until her death in 1873, Marie Françoise was often alone on the rock of Kolopelu with some girls. Occasionally she had a Sister companion. But her compelling missionary vision remained, sustained by her certainty that she was where God wanted her.

Her hidden life bore visible fruit even during her lifetime. When she left Wallis in 1854, her former pupils continued the work she had begun, establishing communities in two different villages to teach reading and catechism to little girls and to take care of the churches. Marie Françoise was called by God to open new pathways in the Pacific not only for the women of Wallis and Futuna, but also for those who followed her in missionary endeavour both from her native France and many other countries.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)