Disciple of Her Son: Mary in the Life of the Church

The Society of Mary

Part 1 of 2

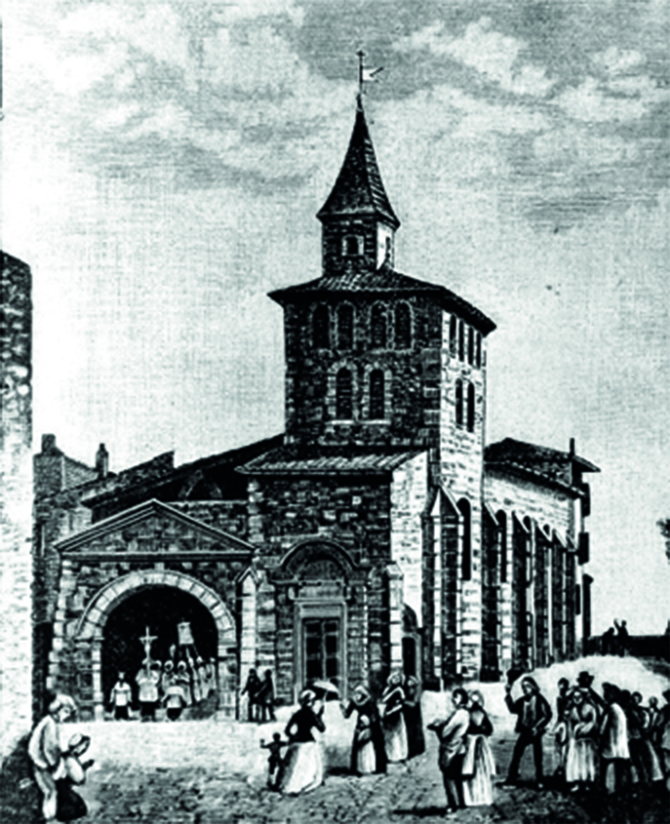

In the early morning hours of 23 July 1816, twelve young men made their way on foot from the diocesan seminary of St Irenaeus across the Saône River and up the Montée Saint-Barthélemy to the top of the hill of Fourvière which overlooks the city of Lyon, France, and into the small chapel of Our Lady of Fourvière. Some of them had been ordained priests the day before; the rest of them would be ordained within the year. They had come so that the leader of the group, Fr. Jean-Claude Courveille, could celebrate his first Mass, assisted by the others, and so that they could all sign a pledge and place it under the corporal on the altar during the Mass. It was a pledge to work for the foundation of a new religious congregation, the Society of Mary, whose members would call themselves Marists.

They mounted the hill in darkness that morning, but dawn was breaking upon them. So also was dawn breaking on the times they were living through. The French Revolution with its reign of terror, its persecution of the Church, the split in the Church between those loyal to the Pope and those who threw their lot in with the Revolution, the dissolution of the religious orders, and the Napoleonic dictatorship, had all come to an end during the previous months. There was hope for the restoration of a French monarchy friendly to the Church, and a restoration of the Church itself to its former position of influence.

How much hope the twelve young men placed in these political prospects we do not know, although they expressed in their pledge the expectation that their project would come to fruition in a political atmosphere that was friendlier to religion than the Revolution and Napoleon had been. Nevertheless, their hopes that morning were grounded in a more secure foundation: some years before, Jean-Claude Courveille had heard in his heart what he took as a message from Mary, the mother of Jesus, asking for the foundation of a religious congregation that would bear her name, the Society of Mary, and that its purpose would be to serve the Church during those difficult times.

Convinced that this was what Mary was calling them to do, they had no doubt that the project would succeed, and that through them Mary would bring peace, reconciliation, and consolation to God’s suffering people. Their hope was grounded entirely in Christ in whom we can do all things (see Philippians 4:13), and in Mary, who was calling them to this work.

It would take twenty years for their project to come to fruition with papal approval for the Society of Mary in 1836. During those twenty years, all but four of the twelve abandoned the project, including even Fr Courveille, who proved unsuited for the leadership of such an undertaking.

But many others joined the project, and a new leader emerged, one of the original twelve who had climbed the hill of Fourvière in 1816: Fr Jean-Claude Colin. He seems to have been particularly graced and inspired with insights into the spirit that must characterise the new Society, the spirit of Mary herself. Already in 1816, in the town of Cerdon in France, where he was assigned as assistant to his older brother Fr Pierre Colin, the pastor of the parish, Jean- Claude Colin began to jot down some ideas for a Rule for the group. He also worked with Courveille in the first attempts to seek approval for the project from the Pope. Eventually, after Courveille had left the project, Colin was chosen to lead the group and to spearhead the efforts to obtain papal approbation. In 1836, when Pope Gregory XVI finally gave approval to the Society, Colin was elected Superior General.

It was Jean-Claude Colin, then, who shaped the Society of Mary, and who communicated to the Society its spirit, its spirituality, and an approach to ministry inspired by the example of Mary.

Colin could see quite clearly that it was not possible to turn back the clock. There was no going back to the way things were before the Revolution. A new world was coming into being, and it required a new approach to ministry. In fact, Colin perceived that the condition of the Church during the nineteenth century was in many ways similar to that of the earliest days of the Church.

After seventeen hundred years during which the Church had held a position of power in the world, it now found itself once again living in a world hostile to the faith. Atheism and radical secularisation were in the ascendancy. But far from bemoaning the situation, Colin saw it as an opportunity to give the Church a fresh new start.

But what was to guide the Marists in their endeavours to help the Church make this new start? Colin looked to the early Church and to Mary’s presence there. He said that it had been revealed that the Marists should take the early Church as their only model.

Fourvière chapel

When he looked to the early Church, especially as depicted in the Acts of the Apostles, Colin was impressed by the fresh, vibrant faith of the first believers. He noted that those first Christians were of one mind and heart (Acts 4:32). He saw much collaboration and little competition or conflict. He observed that the apostles were poor men who neither sought wealth for themselves nor hoped to impress people with the wealth and prestige of the Church, which unfortunately came to characterise the Church in later centuries.

Thus, Marists were to reject every form of greed and ostentation. When possible, they were to work without recompense. They were to collaborate with other religious, and with lay people, and were so to cooperate with the bishops that the latter might consider the Marists as “their own”.

This article first appeared in Forum Novum

www.maristsm.org/en/forum-novum.aspx

It is used with the permission of the editor, Fr Alois Greiler SM who notes, For a long time, Fr Keel worked on a manuscript combining his work with Scriptures and his expertise in Marist studies. This is Chapter 14 of the manuscript, a work intended for a general audience.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)