The Mission Changed the Missionary

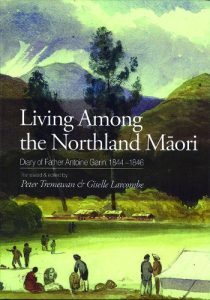

The following is the text of a speech given by Fr Mervyn Duffy SM at the launch of the book by Peter Tremewan and Giselle Larcombe, entitled Living Among the Northland Māori: Diary of Father Antoine Garin, 1844-1846 (600 pages, Canterbury University Press).

The following is the text of a speech given by Fr Mervyn Duffy SM at the launch of the book by Peter Tremewan and Giselle Larcombe, entitled Living Among the Northland Māori: Diary of Father Antoine Garin, 1844-1846 (600 pages, Canterbury University Press).

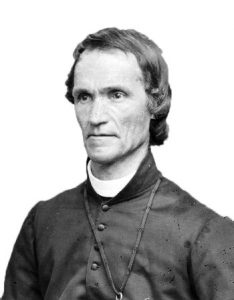

As a child, I was a parishioner of St Mary’s Church, Nelson. A source of pride for that Parish was that it had been founded by a saintly missionary – Father Antoine Garin. He died on this day one hundred and thirty years ago, but the impact of his life was such that he has not been forgotten in the community where he spent the last thirty-nine years of his ministry.

Fr Antoine Garin was the founder of Nelson Catholic Parish, the first resident Priest in the South Island. Before that, he was the founding Priest of Howick and Panmure parishes in Auckland. Before that, he worked as a missionary to the tribes of the Tai Tokerau, from a base near Tangiteroria; about halfway between Whangarei and Dargaville.

Garin, a Frenchman, worked among Māori in Northland, with Irish Fencibles in Auckland and with English settlers in Nelson. In each of these communities, despite being an outsider, he made a significant impact and had a high public profile well beyond his Catholic congregations.

His own talents obviously contributed to this – he was charming, intelligent, musical, good with languages, an excellent communicator, and he cared deeply for the people he worked with. However, on the basis of reading this book, I want to suggest another reason for Garin’s ability to have an impact on the society of his time.

A missionary, by definition, is someone sent by one country or faith community to bring about change in another people. To bring them the good news of Jesus Christ, to offer them a new religion.

That Garin was a change-agent in the Northland area is evident from his diary. A recurring theme running through his notes of his daily activities is a deliberate and conscious attack by him on the tapu system. He taught that Christian baptism freed believers from having to fear Satan or “the Māori god” – if they breached tapu they would not fall ill. That was a change which he sought to achieve. His presence also had consequences that he did not intend. He traded large quantities of tobacco with local Māori for services, thereby contributing to a new addiction and health hazard.

However, I claim that the diary also makes evident the impact that Kaipara, Mangakāhia and Whangarei Māori were having on Antoine Garin. The Mission also changed the Missionary.

I was fascinated to read of how mobile the Northland tribes were and just how much travel and interaction was being done along the rivers and round the coast of the Northland, and how the chiefs with whom Garin dealt were careful to maintain their mana through very public encounters. It was largely an oral culture and public perception was much influenced by story and rumour. Symbolic actions played a huge part in the interactions between tribes. The gift of a case of ammunition to a chief was an invitation to join with another tribe in making war. Solemnly throwing that ammunition in the river before many witnesses was an eloquent refusal to participate.

Garin witnessed mock battles, haka challenges, and individuals being roughed up over insults to the honour of a chief or his mother. All very public, much of it involving ritual behaviour and posturing; the careful maintenance of status.

Garin experienced his own mana as a church leader being diminished by some of his converts being widely known to have committed adultery.

Garin learnt the importance of utu, gift-exchange, the value of being known as an honourable man and a man of peace. He acted as translator between Māori and Pakeha, translating not just the words but also explaining the ethics and ways of the one to the other.

I contend that from the chiefs; Tirarau, Rako, Wetekia and Hoane Papita, and from his young Māori companions, Kaperiere and Matiu, Garin the foreigner, learnt how to conduct himself as a high-profile public figure in Northland. He learnt the value of listening to local advisers, he learnt how to maintain his own mana, how to gather people together, how to celebrate, how to mediate, how to tell a good story, and how to act in a newsworthy fashion.

His four years in the Northland were when Garin honed many of the skills which were to serve him well as a public figure throughout the next 43 years; the rest of his life and work in New Zealand.

I recommend this book to you for the insights it gives into the education and development of a great man and of the world he experienced. Living among the Northland Māori involved learning from and about the Northland Māori. This book gives us a chance to look over Garin’s shoulder, to see what he considered worthy of note across the time when he had privileged access to the culture that was dominant in 1840s Aotearoa, before it was impacted by the most negative effects of colonisation.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)