Story of a Story

By Stephen Sparrow

St Thérèse of The Infant Jesus would almost certainly have remained unknown to the world at large had it not been for her elder sister Pauline, who, in 1895, was Prioress of the Lisieux Carmel where Thérèse lived. In passing we should also note that of Thérèse’s four sisters, three of them were also at that time living with her under the same convent roof. One winter evening as the community was gathered at recreation, Thérèse was sitting close to the fireplace and relating to those around her some childhood memories. Her sister, Mother Agnes, was listening and in almost jocular fashion ordered Thérèse to commence writing a record of her life from childhood through to the present time.

Even though Pauline was her blood sister, Thérèse was obliged by her vow of obedience to act on this almost casual order. In passing we should note that most of us have heard criticism of religious for their complete subservience to the will of those in authority; but in defence of this compliance, we should be aware that for Religious, be they priests, monks or nuns, acceptance of this authority is first and foremost an act of their own will – i.e. it takes an act of one’s will to agree to submit one’s will. So although Thérèse was not given any special time to complete the task, she set to it, using the quietness and privacy of her own cell, seated at a little desk and writing into a small school exercise book by the light of primitive lamp. Thérèse finished writing what later became known as Manuscript A on January 20 1896 and dutifully and silently handed it to Mother Agnes who accepted it without comment. Two months later an election for Prioress was held. The vote was close and Mother Agnes lost to the austere, tough minded, Mother Gonzague.

The Martin sisters, who all became Carmelites

Because of the tension surrounding the election, Mother Agnes was afraid that the new prioress would simply burn Thérèse’s document when she got hold of it and it was several months before she summoned the courage to tell Mother Gonzague of its existence. However, Mother Agnes cleverly skirted the problem by describing the manuscript to the new prioress as something useful for the time when Thérèse’s obituary would have to be written. Fortunately, Mother Gonzague liked it and at Mother Agnes’s suggestion, she ordered Thérèse to continue writing, with the emphasis now on her spiritual thinking and her life in Carmel. Thérèse commenced Manuscript C on June 3, 1897 and, because of deteriorating health, she was allowed the luxury of time specifically to write. She ceased writing on July 8, 1897, when she became too ill to continue.

Between the completion of Manuscripts A and C, Thérèse received a written request from another older blood sister, Marie (Sister Genevieve), who sensing her younger sister’s sanctity, insisted on knowing more about this “little way” she lived by. The nearly five thousand word reply she received is the incomparable Manuscript B, written in Thérèse’s scant spare time inside just five days.

St Thérèse of Lisieux - Photo Wikipedia

Sister Thérèse died from tuberculosis on September 30th 1897. A short time later, Church authorities granted permission for the combined manuscripts to be published and distributed under the title Story of a Soul. Before her death Thérèse had given her sister (Pauline) Mother Agnes, editorial freedom to make the writing suitable for publication – to ‘dress it up a little’ if necessary – always Thérèse envisaged her writing as being intended only for family and maybe close friends. Irrespective of that, Mother Agnes took to her task with diligence and enthusiasm and almost exactly a year after Thérèse died the first printing of 2000 copies was ready for sale and distribution. What was not known until more than fifty years later was the extent to which Mother Agnes had altered Thérèse’s writing. When in the early 1950s the original manuscripts were examined by experts, infra red technology was used to sort Thérèse’s text from what had been erased and/or overwritten. It was calculated that the total number of changes executed by Mother Agnes numbered at least 7000. Most were small, many involving only a single word, but then there were the others; passages where Thérèse’s meaning was diluted or distorted, and in some cases her intended meaning vanished as Mother Agnes made changes that fitted with her own spiritual comprehension. The remarkable thing is that Story of a Soul, even in its dilute form had an enormous impact on all who read it. The corrected editions only became available in 1956. It was almost as if the restoration of the original manuscript rhymed with the changes in the Catholic Church emanating from Vatican II in the early 1960s.

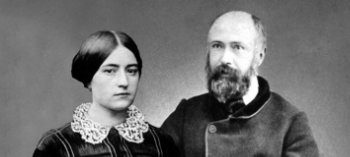

St Thérèse’s parents, Sts. Zelie and Louis Martin

Today the various translations of Thérèse’s autobiography exceed sixty with probably at least forty different languages involved, and in readership terms the numbers must be colossal. From the moment of its first appearance, the book generated both enthusiasm and controversy, quickly starting an avalanche in the writing and publishing world. Books in many languages devoted to some aspect of Thérèse’s life and spirituality began appearing at the rate of nearly one per month for the next 100 years. A few were nothing other than hatchet jobs, written by embittered atheists and agnostics determined to deliver verdicts of mental illness to explain Thérèse, but in spite of their exertions, her genius continued to shine and attract an enthusiastic readership well beyond Catholic circles.

If all that were not enough, in the early years much work was done retouching photos and producing sugary holy cards to confect a particular image of the saint. American Catholic author Flannery O’Connor, writing to a friend, told how she read and enjoyed Fr Etienne Robo’s Two Portraits of St Thérèse of Lisieux, which in part exposed this effort. O’Connor said the book, which was disliked by the Lisieux Carmel, greatly increased her devotion to Thérèse. Fr Vernon Johnson, who converted from being an Anglican Friar to Catholicism in the 1920s, encountered Thérèse’s autobiography before his conversion. It was recommended to him by an Anglican nun in a retreat house. The first few chapters appalled Fr Johnson with what he saw as mawkishness but as he read further, he found it impossible to lay the book aside and his devotion to Thérèse took root and flourished. After his conversion he made numerous pilgrimages to Lisieux. Let’s face it, the initial encounter with Story of a Soul can have the same effect on us, but, if we stay on the case we will, like Vernon Johnson, discover many fine passages of deep profundity as well as the sharp insights into human nature the story is strewn with. In the final analysis, Thérèse’s story grips on account of its white-hot witness.

Looking back, we can see so many factors that each by themselves could easily have derailed publication of Story of a Soul. That nothing got in the way can only point to Divine Will ensuring the survival of what is, without any doubt, the greatest modern work of spirituality. That seemingly chance directive to Thérèse from her elder sister in 1896 resulted in her being lauded as easily the Church’s greatest modern saint as well as being only the third woman to be declared a Doctor of the Church.

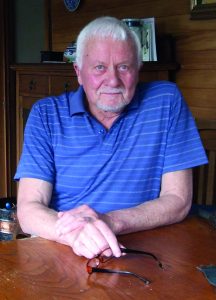

Stephen Sparrow is retired, and reads and writes for pleasure. He has a strong interest in ornithology, botany, NZ outdoors and conservation matters.

He is the author of Rahnuk, available via Amazon.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)