A Nightmare and its Consequences – (2)

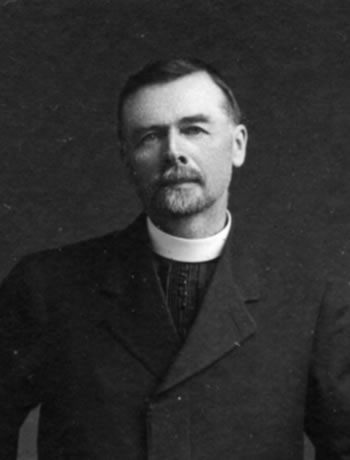

Fr Delachienne sm, also known as Pā Hohepa and as Fr Delach

From the Golden Jubilee Speech of Fr Delach

The second part of Fr Delach's address to the students at the Institution Saint-Vincent at Senlis, Oise, which is about 40 km north of Paris, translated by Elizabeth Charlton, NZ Province Archivist.

By defeating the spell placed on bim by the tohunga, the witch doctors, Fr Delach broke their influence. According to one of the chiefs, this 'proves ... that there is neither god nor devil above the God of the Christians.'

This story of this victory over evil spirits had a great effect in the area and spread like a prairie wildfire to the surrounding villages. As superstition then played a preponderant role in daily life, I suddenly became an important person in their eyes, so much so that some of the elderly went as far as to say that I was a super witch doctor who could become dangerous and would need monitoring.

What would they have said, if they had seen me speak to them through an object like this (the microphone)? But the Catholics triumphed. They were proud. The witch doctors could do nothing to their priest. He was thus stronger than them and would protect them in the future from devilry and spells. They resolved to make use of me for this purpose, but without my knowledge obviously, because to disclose the existence of witchcraft, was equivalent to desecrating the supernatural and promised to the indiscreet the worst punishments from the Māori devils.

Here is an example. One time I had baptised all the inhabitants of a small Māori village, about 20 or 25 people. Among them was a charming young man – but all young people are charming. He was 16 or 17 years old and named René. As our district was immense, there were a certain number of villages that we saw only once every three months, others every six months, and a few, once a year, as was the case of this one.

One day as I was returning from a Catholic meeting, accompanied by a few Māori, our train passing a few kilometres from this place, the idea suddenly came to me to make the most of the occasion to visit. An inconceivable idea, as in the Māori world, it is not permitted for a leader to leave his companions during the journey. But this idea soon became an obsession. I spoke about it to the Māori, who saw the supernatural straight away, and encouraged me to fulfil this idea; it was 10 am.

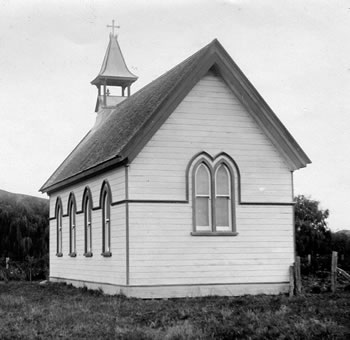

The Immaculate Conception Church, Pakipaki, Hawke's Bay, the parish to which Fr Delach was first appointed when he arrived in NZ.

The train stopped at a small station, about 4 or 5 kilometres from the village. I got off and started to walk. I had been walking for about 15 minutes when I saw two women in the distance who appeared to come toward me, but as soon as they recognised me, they turned back. An ominous sign, I thought to myself, but on mission one has to be ready for anything. I continued my journey. I had been seen and the message passed on. However, the children did not come to meet me as was their wont. I entered the village – no one in sight. I started to get cold in the back. I went straight to the chieftainess’ house. She opened the door, shook my hand silently and then said quietly, “My son, René, is in agony. Come in. He’s waiting for you.”

I went in. René, the young man who I had baptised and whom I had thought I would make a catechist, was there lying on a mattress on the ground, carried away by some fever. There were no doctors hereabouts. He saw me. Smiling and putting out his hand, he said, “I’ve been waiting for you. I’m going to confess. Then you will give me the extreme unction, there’s just enough time.” He confessed, I gave him the extreme unction. As I was closing my book to give him a last blessing, he smiled at me. His mother looked at me, frightened. René had entered into his eternity.

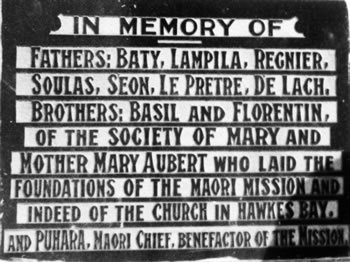

A plaque at Pakipaki on which Fr Delach's name, among others, is recorded

Women came to cry as is the custom. When they started to wash the body, the chieftainess took me aside and spoke to me. “My son, René, had been sick for a few days, an intense fever undermined him – they say typhoid. This morning about 10 o’clock, he said, 'Prepare dinner for Father. I’m telling you he’ll arrive in a little while.' We believed it was the delirium of death and we all felt very sad. Seeing that no one moved, he insisted, 'Prepare dinner for Father. I’m telling you he’ll arrive in a little while. I can see him. He’s rushing, and you know he is sick.' So to make him happy, I had the meal prepared. On the off chance, I sent two women to meet you. But when they saw you they came back, overwhelmed with grief, for they had concluded that your arrival coincided with the child’s death.” She paused and said, with every syllable strangling her, “Come and eat what René had had prepared for you. He’s the one inviting you.” The food was tapu. That means under bad spells. She served me with fear and trembling. You will find out a bit more later.

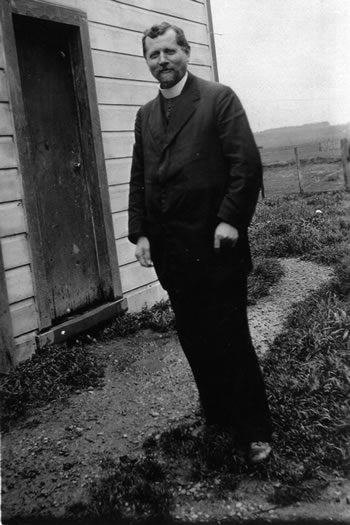

Fr François Melu sm with a group of parishioners at Pukekaraka, Ōtaki, in May 1914. Fr Delach is seated to the right

Allow me, gentlemen, to bring your attention for a moment to this little fact which is not unique in my missionary life. An obsessive idea came to me on the train around 10 in the morning. To fulfil it, I had to change my itinerary, break Māori protocol, and perhaps to start an adventure in order to visit the village. At the same time, and in this same village, a dying young man announces my arrival and asks that a meal be prepared for me. He is not believed and he insists. He sees me. I am hurrying. I am sick. I arrive in the village, the dying lad says to me, “I was waiting for you, I am going to confess. You will give me the extreme unction. There is just enough time.” He dies as soon as the rites are completed. Explain that by intuition, suggestion, telepathy or whatever other ways you wish, but I believe that here we have to accept the great waves of divine intervention. When Māori convert, they have a simple but strong and comforting faith; faith that the good God loves and that he always rewards even in this world. But let us return to our story.

I have seen the real tapu since, and up close. We could perhaps define it as a system of penal law forming an integral part of Māori religion and based on the fear of their gods and of their tohunga.

Fr François Delachienne sm, possibly in Ōtaki, year unknown

The word, tapu, has as its first meaning 'holy, sacred,' what we should not touch, such as the Sanctity of the Mass, for Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord, one says, Tapu, Tapu, Tapu te Ariki. All that is tapu in Māori religion was under the immediate and effective custody of their gods, which were only evil spirits. Woe to whoever touched. A sudden death was usually the manifestation of their vengeance, and all those who contravened the laws of tapu ordinarily suffered the same fate. On the other hand, the tohunga could declare anything tapu, for example, a pile of potatoes in times of scarcity. Everyone in the village would die of hunger rather than to expose themselves to the vengeance of the bad spirits by taking them. Only he who had placed a tapu on something could use it.

There were different types of tapu. But there was one which was the nightmare of the Māori -- the one which could be contracted in certain circumstances through contact, voluntary or not, with death, or something from beyond the grave. So I saw the great Pacific Ocean declared tapu over an area of about 50 kilometres long by 15 kilometres wide, because a Māori had died in the area. Over the year that the tapu lasted, not one Māori person, big or small, went near the shore, fearing they too would become tapu. Needless to say, the Māori would not have been surprised if the Normandie1 had sunk with all hands in the same location.

To be continued

1 The Normandie was a transatlantic ocean liner (1932-1946), the largest and fastest vessel afloat when entering service in 1935

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)