A School for Prayer (4)

The Way of Beginnings

By Fr Craig Larkin sm, 1943 - 2015

From the Church Fathers

The Fathers of the Church have left us some descriptions of how Christians prayed in the first centuries of the Church.

St John Chrysostom: all take it for granted that every Christian would pray night and morning

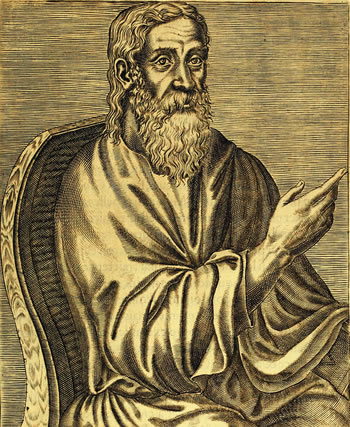

Clement of Alexandria, by André Thévet, 1584

Clement of Alexandria: there were fixed times assigned to prayer, for example the third, sixth and ninth hours

The Didache: it was presumed that Christians prayed three times a day

Clement of Alexandria: prayer contained ‘canticles of praise and Scripture readings before meals and before retiring to rest’

Clement of Alexandria and Origen: people prayed ‘with uplifted hands and eyes raised to heaven’

Origen: the Lord’s prayer is always part of prayer

Tertullian: one’s hands need not be washed every time one prays: they are already clean as a result of baptism, and so can be raised to God, but moderately so

Tertullian: at the start of morning prayer at least, as well as on fast days, one should kneel for prayer

Four Basic Attitudes

Four basic attitudes underpinned all the practice of prayer in the early Church:

1 Desire for God: Remembrance of God

A first characteristic of early Christian prayer was the Remembrance of God (Mneme tou theou). It was the practice of keeping God and the thought of God constantly in mind: not saying particular prayers, but keeping the thought of God alive, as a lover keeps the thought of the beloved always in mind. It flows from another characteristic of Christian prayer – the desire for God.

St Basil spends much time in his Rule for Monks on this point. Union with God, he says, is made up of submission of the will to the wishes of the Lord, and constant remembrance of the Lord himself. He says that the goal of remembrance of God is to be able always to recognize the will of God.

2 Union with God through Martyrdom

Passion and desire characterize the great men and women of the early Church.

Both before and after his conversion, St Paul is a man passionately committed to God. The difference was in how he understood fidelity to God. Before his conversion, his desire was to keep the Law. After his conversion, his passion was to know Christ. Relationship with Christ and with people is all-important. The surest sign of this union with Christ was seen in martyrdom, which was the summit to which every Christian aspired. Ignatius of Antioch is an outstanding example of this attitude: Let fire and the cross; let the crowds of wild beasts; let tearings, breakings, and dislocations of the bones; let cutting off of members; let shatterings of the whole body; and let all the dreadful torments of the devil come upon me: only let me attain to Jesus Christ.

Pray for me that I may have both inward and outward strength, that I may not only speak words, but that I will be a man of deeds; that I may not only be called a Christian, but that I really will be one.

Christianity is not a thing of silence, but also of greatness in actions.’

When martyrdom, the shedding of one’s blood, no longer became such a strong possibility, virginity for the sake of Christ became the way of professing one’s desire for Christ. Virginity was known as ‘white martyrdom.’

3 Fraternal love in the Church

Christian spirituality is following Christ. Christ established a Church, a communion, in which his followers would find the Way to follow him. Christian spirituality cannot be lived outside the communion of the Church, because it is in the Church community that we can be one in fraternity, as Jesus prayed (John 17).

Union of brothers and sisters in the Lord and communion in the Lord with the bishop of the Church is the sign of Christ’s presence. Ignatius of Antioch and Clement of Rome both insist on unity within the Church as a foundation for Christian spirituality.

4 Celebration of the Eucharist

St Justin Martyr gives evidence that very early in the Church’s existence the celebration of the Eucharist was not only common, but also clearly established and structured. He writes:

On Sunday we have a common assembly of all our members, whether they live in the city or the outlying districts. The recollections of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as there is time. When the reader has finished, the president of the assembly speaks to us; he urges everyone to imitate the examples of virtue we have heard in the readings. Then we all stand up together and pray.

On the conclusion of our prayer, bread and wine and water are brought forward. The president offers prayers and gives thanks to the best of his ability, and the people give assent by saying, “Amen.” The Eucharist is distributed, everyone present communicates, and the deacons take it to those who are absent.

The wealthy, if they wish, may make a contribution, and they themselves decide the amount. The collection is placed in the custody of the president, who uses it to help the orphans and widows and all who for any reason are in distress, whether because they are sick, in prison, or away from home. In a word, he takes care of all who are in need.

We hold our common assembly on Sunday because it is the day our saviour Jesus Christ rose from the dead.

Father Giltus Mathias, Sunday Eucharist at St Mary's, Blenheim

No one may share the Eucharist with us unless he believes that what we teach is true, unless he is washed in the regenerating waters of baptism for the remission of his sins, and unless he lives in accordance with the principles given us by Christ.

The prayer life of the early Church, though it had definite shapes to it, was characterised more particularly by internal attitudes, best described as:

Union with God

in Christ

through the Church.

To be continued

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)