Fr Delphin Moreau sm – ‘A man for all seasons’

Fr Neil Vaney sm

One could say of Jean Claude Colin, the founder of the Society of Mary, that his vision was one of a mission without frontiers. By that, I mean he came to conceive of a spirituality, an ethos, even a methodology, like a fragrant oil that could be poured into a huge diversity of jars. Unlike other congregations, Marists were not to be limited to a particular place or ministry, but rather, shaped according to a particular embodiment of Mary’s personality that could be expressed in a myriad of different contexts. We see that played out in the first groups of missionaries sent to Aotearoa New Zealand. Think of Garin, educator, parish priest, artisan; or Leterrier, seminary lecturer and headmaster; or Yardin, missioner, procurator, vicar provincial, parish priest.

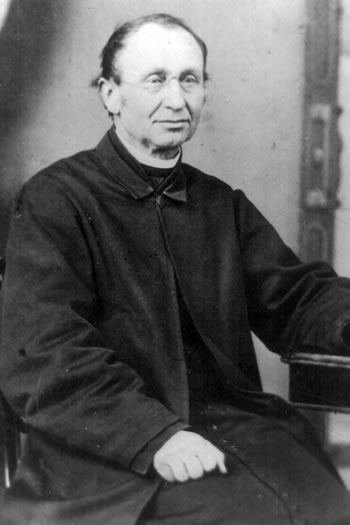

Fr Delphin Moreau sm

The multi-talented Moreau

Delphin Moreau was cast in the same mould. Many would know of his labours for a decade in gold-boom Otago, but in fact his talents and labours were far more diverse. First, he was a fine educator. Arriving in Nelson in 1851, he spent eight years teaching French, Latin and Mathematics in Fr Garin’s acclaimed school. Among his pupils was Francis Redwood, just twelve years old. Twenty-four years later, Redwood, now bishop of the vast central diocese, all of New Zealand except Auckland and Otago, came to bless his old teacher’s newly-built church in Palmerston North, and to praise what he had accomplished.

The apostle to the Māori

Before being a gifted teacher, Moreau had been an able student. On his arrival in Auckland in 1843 he was dispatched to the Bay of Islands to learn Māori, spending four years gaining mastery of te reo. He was very successful. We witness this during his next spell in the Bay of Plenty, preaching and catechising in Opotiki, Whakatāne, Rotorua, Maketu and Taupō. With little support and meagre finances he built up a flock of 300 Catholics in Opotoki, erecting a chapel and a school for seventy children. After the collapse of the Marist presence in Auckland, he was moved to areas where there were few Māori: Nelson and Otago. Yet even in the Presbyterian stronghold of Dunedin, during his last three years, he was a devoted preacher and comforter of the Māori who had been exiled far from Parihaka for attempting to resist colonial land-grabs, visiting and celebrating with them every Sunday that he was home in the city.

When he left Nelson, Moreau spent several years based in Wellington, where much of his energy was poured into the flourishing Māori community in Ōtaki. Returning there after his long stint in the Otago goldfields, he hoped to pick up where he had left off in 1859. But the New Zealand wars, land confiscations, and apparent desertion by the missionaries, had turned many Māori away from Christianity. So Moreau’s energy turned more towards the growing settlements of the Manawatu: Ashurst, Fielding and Palmerston North. Old and worn out when he finally departed Palmerston North, it seems that he may have volunteered to return to live with the people of the Whanganui river, working from a base in Jerusalem. A bare seven months later he was forced to go back to Whanganui, soon to die.

St Joseph’s Church, Dunedin, build under

Fr Moreau’s direction in 1862

The builder of churches

When the newly consecrated bishop of Dunedin, Patrick Moran, arrived in February 1871, it was not long before he expressed dissatisfaction with the temporal state of his diocese -- few and poor churches, a paucity of vestments, liturgical books and altar vessels. He could not believe that such a gold-boom district could appear so threadbare and poor.

In his defence, it is sometimes said that Moreau was, like St Paul, an itinerant missionary always on the road, without the luxury of time or money to build churches. This is probably too simple a picture. We need first to understand the extraordinary character of the Otago region.

Fr Delphin Moreau sm

in later years

On his first trip to Dunedin in 1859, Moreau celebrated Mass at the home of Neil McGregor, to a congregation of twelve of whom eight were Catholics. There were probably about 80-90 Catholics in the entire region. By 1862 there were 184, whereas Poupinel, the official Marist visitor from France, estimated that by 1864 that number had risen to 15,000 – 20,000 as the result of gold discoveries.

This vast influx, mainly Irish miners coming across from Australia, were notorious wastrels, famous for carousing and womanising. Despite this, Moreau was able to raise the £1,250 that served to open the new chapel of St Joseph in Dunedin in July 1862, and within the next few years had managed to put up two temporary chapels out in the gold diggings.

Before coming to Dunedin he had already built churches in Opotoki and Rotorua. Back in the North Island, he later had a hand in churches in Otaki, Fielding, Halcombe, Foxton, and Palmerston North. He may have been a wandering missionary but he was clearly a good administrator and planner as well.

The gift of adaptability

One of the most striking features of Moreau’s personality was his remarkable ability to adapt to very different milieux and demands. He came to convert Māori and spent years ministering to wayward Irish. His churches were dance halls, hotels, court rooms and miners’ tents in the bush.

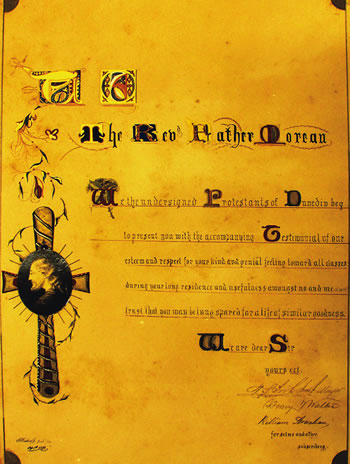

A Frenchman of heavy accent, he won the sympathy and admiration of the staunch Scots of Dunedin, who offered glowing testaments, an illuminated address, and a purse full of guineas on his departure in 1871.

When polemic and invective between Catholic and Protestant were not uncommon, and were to flourish under Bishop Moran, he bridged faith-divides. He had taught Catholics and Protestants in Nelson, and offered Mass for both on the goldfields. His gift of embracing whatever ministry, in whatever milieu to which he was called, is not common. It was the fruit of a deep faith, flourishing in an equable and humble disposition.

The scroll reads:

To the Revd Fr Moreau

We the undersigned Protestants of Dunedin beg to present you with the accompanying Testimonial of our esteem and respect for your kind and genial feeling toward all classes during your long residence and usefulness amongst us and we trust that you may be long spared for a life of similar goodness.

We are dear Sir

Yours ect (sic)

(signatures)

for selves and other subscribers

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)