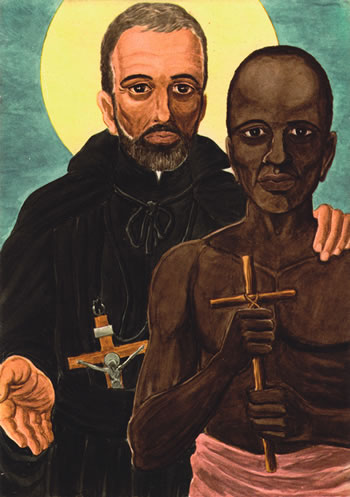

St Peter Claver

by Tricia O'Donnell

This year marks the 210th anniversary of the Act to abolish slavery in Britain and the United States. William Wilberforce, of course, is well known for the part he played in bringing about the abolition of slavery, but less familiar is the man who influenced him, later to become a saint.

Peter Claver’s work among the slaves of 17th century South America made an enormous impression on Wilberforce, who would quote him on occasion during his years of political campaigning. The man who would eventually become the patron saint of slaves and seafarers, daily practised the ethos of Christianity in the love he gave to all he met. Little wonder he became known as the ‘Slave of the Slaves.’

Peter was born in 1580 into a prosperous farming family in the Catalan village of Verdu, some 87 kilometres from Barcelona. His strict Catholic upbringing shaped him throughout his childhood, so it was no surprise to those who knew him that he would join the Society of Jesus as soon as his university studies were over. He had long had a calling to go to the Spanish colonies, and in 1610, at the age of 30, he was sent to the port city of Cartagena in the Kingdom of the New Granada, now known as Colombia, in South America. Peter was eventually ordained there, but in the years before his ordination, the slave trade was to have a huge impact on him.

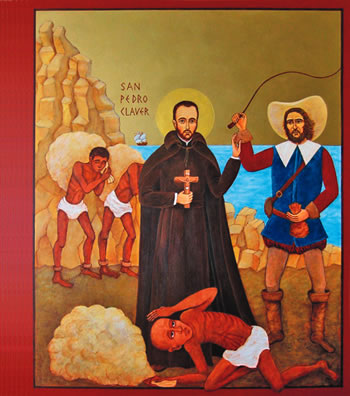

Cartagena was known as the ‘Treasure Port’ of the Americas. Around 10,000 slaves arrived there every year from Angola and the Congo; those who died en route – and it’s believed about one third did so – were thrown into the sea, as were those considered unfit to be sold for whatever reason. Dead or alive, they were treated like animals, and for those who survived to reach shore, the nightmare continued long after they were publicly sold, as often they were cruelly treated by the people who bought them.

Cartagena was known as the ‘Treasure Port’ of the Americas. Around 10,000 slaves arrived there every year from Angola and the Congo; those who died en route – and it’s believed about one third did so – were thrown into the sea, as were those considered unfit to be sold for whatever reason. Dead or alive, they were treated like animals, and for those who survived to reach shore, the nightmare continued long after they were publicly sold, as often they were cruelly treated by the people who bought them.

Long before Peter Claver arrived on the scene, another priest had made it his life’s work to help the slaves arriving in the port. In the 40 years that Father Alonso de Sandoval, S.J. had been ministering to the Africans, he had learnt their customs and their language in order to communicate better with them. He became Peter’s mentor, and by the time the young priest was ordained he was determined to carry on with Fr Alonso’s work and devote his life to helping these unfortunate souls.

Peter took a hands-on approach from the start. As soon as a slave ship docked at the port, he would be waiting to board, usually carrying food, water and medicines. The holds were crammed tight with bodies, the sick, the dying, the hungry and the frightened – the young priest tended to as many as he was able. Whether embracing lepers or physically cleaning the men’s ulcerated bodies, Peter never flinched from what he felt he was called to do. His philosophy was: ‘We must speak to them with our hands before we can speak to them with our lips.’

Church of St Peter Claver, Cartagena, Colombia, in which the saint is entombed

This he did, on and off the ships. He would follow them into the market place where, crowded into compounds, they would be examined by would-be buyers. As they waited to be sold, Peter would be attending to as many as he could with food, medicine and tobacco. This ministration continued after the sale, and in between ship visits when he would travel around the plantations helping them spiritually, emotionally and physically.

Wherever he went he carried the tools of his trade: rosary, bible, holy water and crucifix. Throughout his years of ministering it’s believed he converted around 300,000 slaves to Catholicism.

Of all the stories told of Peter Claver, one of the most well-known concerned his cloak. Whenever someone needed it, it was used -- to protect the wounds of a slave, a pillow for the sick or dying, a funeral cloth for the dead or to cover the sores of a leper. It was believed to be sacred; to touch it would bring healing, and it became more and more tattered as people demanded relics of the precious cloth.

Peter Claver’s mission did not rest solely with the slaves. While he attended to the spiritual needs of other members of society, he was astute enough to know that the overall welfare of the slaves depended on changing people’s hearts towards them. He was often seen preaching in the market square and frequently visited the sick, the needy and those in prison. Criminals sentenced to die had the company of Fr Claver with them as they went to the gallows; brandy accompanied their final blessing. But it was the slaves who were his priority. He had a God-given gift of unconditional love and compassion for these people who desperately needed someone on their side. Not for him to right the wrongs of society or to preach to the authorities about a corrupt system, for he was too busy attending to their needs.

Peter kept track of each slave he baptised and once a year would seek them out to make sure they were being treated well, lodging with the slaves rather than in the comfort of the plantation houses. He wasn’t particularly popular with some of the owners, sometimes being physically threatened, but he was undaunted. His concern was for the slaves, ensuring their Christian and civil rights were honoured.

Peter kept track of each slave he baptised and once a year would seek them out to make sure they were being treated well, lodging with the slaves rather than in the comfort of the plantation houses. He wasn’t particularly popular with some of the owners, sometimes being physically threatened, but he was undaunted. His concern was for the slaves, ensuring their Christian and civil rights were honoured.

After devoting his life for more than 40 years to ministering to the slaves, Fr Peter’s health finally began to fail. The last four years of his life were spent bedridden, and he was, ironically, often neglected and abused by the former slave sent to look after him. Typically characteristic of him, he bore no grudges and accepted his situation stoically. It was, he said, just punishment for his sins. However, his death on the 8th of September 1654 brought crowds in from the city to pay their last respects to the man who had been such an integral part of their community.

Two hundred years later, on the 20th of July 1850, Peter Claver was beatified by Pope Pius IX and was later canonised by Pope Leo XIII on the 15th of January 1888. Today, his name has been given to numerous schools, hospitals, parishes and missions, as well as continuing his work through the Apostleship of the Sea. In 1909 the Knights of Peter Claver was founded, which today is the largest African-American Catholic lay organisation. He is buried in the church which bears his name in Cartagena, Colombia, and nearby stands a statue of Father Claver deep in conversation with a slave as they walk through the city streets -- a fitting tribute to the Apostle of Cartagena, who truly lived by his own maxim: ‘I must dedicate myself to the service of God until death, on the understanding that I am like a slave.’

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)