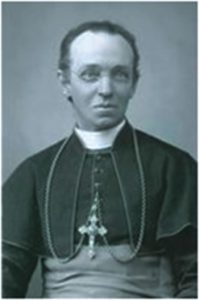

The First Bishop of Christchurch

Bishop John Joseph Grimes sm

This is an edited version of a lecture given on 13 August 2015, commemorating the centennial of Bishop Grimes’ death.

Introduction

John Joseph Grimes was born in Bromley-by-Bow, East London, in 1842. His father was a seaman, both parents illiterate. What was the journey that allowed this erstwhile Cockney on his death in 1915 to be hailed by the conservative Christchurch press as a deeply respected religious and civic leader?

Though he died as a true Cantabrian, Grimes stands out for his international vision and experience. His primary schooling was at the hands of newly arrived French Marist Brothers in Whitechapel, then off to college in France. Following this he arrived at the Marist College of St Mary’s Dundalk where he trained as a priest, after which he became a teacher of English and Classics at the college. Next we find him as Rector of Jefferson College, deep in Louisiana. After seven years of difficult ministry and a savage bout of yellow fever he returned to England as assistant novice master at the Marist seminary in Paignton. There he taught a very diverse mixture of English, French and Irish students. He also took on what amounted to the role of parish priest, the first Catholic clergyman since the Reformation in Devon.

One is struck by the huge diversity of roles he had held by the age of forty: teacher, pastor, religious formator and community leader, in a great variety of different settings and diverse cultures. A piece of advice he received from the Marist Superior General when he set off for his post in the USA: tell them priests should not be hunting – and if they do it, do it in secret!

The Fighting Irish

In 1895, seven years into his work as Bishop, Grimes preached a series of public talks entitled ‘The Re-union of Christendom,’ attended by a good number of non-Catholics. Not surprisingly, he was the recipient of brickbats from both ardent Protestants and defiant Catholics. He did not let such criticism daunt him in his efforts to break down Protestant/Catholic antagonism and misunderstandings. On his death, even the Christchurch Press commented, “The Canterbury public, in mourning his death … is lamenting the removal of one of its most distinguished and helpful citizens.” This praise was won by brave decisions. One such came in the letter he issued in April 1897 in anticipation of the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria, saying of her, “she whom the Almighty has chosen to rule during so long a period is deservedly looked up to as a model Queen and mother, whilst among the noblest of her sex she stands without a rival.” He then ordered a solemn Te Deum to be sung in all the churches and chapels of the diocese on 20 June.

To appreciate the boldness of such a stance we need to understand something of the fiercely pro-Irish and sometimes bitterly anti-English sentiment of the Church over which Grimes was made bishop.

In 1868, the Irish diocesan priest, William Larkin, had been arrested and faced trial on the charges of ‘rout’ and ‘seditious libel’ in connection with the mock funeral in Hokitika of the three so-called ‘Fenian martyrs.’ Found guilty, he was condemned to a year’s gaol; he had already been suspended by Bishop Viard in Wellington the day after his arrest.

In 1868, the Irish diocesan priest, William Larkin, had been arrested and faced trial on the charges of ‘rout’ and ‘seditious libel’ in connection with the mock funeral in Hokitika of the three so-called ‘Fenian martyrs.’ Found guilty, he was condemned to a year’s gaol; he had already been suspended by Bishop Viard in Wellington the day after his arrest.

At this period the West Coast contained the largest proportion of Irish Catholics in the colony, mainly goldminers. So incensed were many of them by what they saw as the lack of support by the French bishop of the popular Larkin, many of them went on a sacrament strike, refusing to attend Sunday Mass at one of the shanty churches scattered about the diggings. Throughout the 1870s the tension had been kept simmering by a number of factors.

First, the pugnacious and outspoken Patrick Moran, who had been appointed bishop of Otago in 1873, and who was soon at loggerheads with the Marists, whom he accused of deserting his diocese and stripping it of valuable assets. His polemics were warmly received by many of the Irish rural labourers who arrived in large numbers under the premiership of Vogel, and who settled in areas such as Kerrytown, Timaru and Temuka. Further afield there was some sympathy for the Fenian ‘patriots,’ or ‘rebels,’ -- depending on one’s point of view -- while at the same time many priests supported the more moderate Land Leagues which fought for a fairer share of productive land in Ireland.

When Grimes landed in 1878, many battles had already been fought over his appointment. While at the First Vatican Council Bishop Viard had met the young Nelson Marist, Francis Redwood, and had been so impressed that he nominated him to be his coadjutor in Wellington. In his turn, Redwood later nominated Grimes as a candidate for bishop in the soon-to-be-erected diocese of Christchurch; the two of them had been fellow students and friends at Dundalk.

As often happens the clerical grapevine was soon at work. A letter announcing that Grimes had been appointed as bishop in Christchurch went from Rome to the USA, and from there to New Zealand, where a number of priests in Wellington got up a petition against the appointment. In this they were assisted by Bishop Moran from Dunedin and some of his most influential priests. As a result the appointment was deferred until after the first Australasian Synod, to be held in Sydney in November 1885. Chairman of this meeting was Patrick Moran, first cardinal of Australia, one of a group of Irish-born bishops who had fought hard against the earlier appointments of English Benedictines as bishops. One of the documents received by the Synod was a petition from the secular priests, O’Donnell in Ahaura, and Walshe in Kumara. One of the outcomes of the meeting was a recommendation to Rome that Dunedin should become the Metropolitan See of New Zealand, and that a diocesan priest should be appointed as bishop of Christchurch. Not to be outdone, the Marists replied with a petition to Cardinal Simeoni of Propaganda, signed by 36 Marists after their annual retreat in Wellington. They offered strong counter-arguments, particularly targeting the nomination coming out of Dunedin of Monsignor Ricardo, the vicar general of Cape Town, inveighing against his age, poor health and total ignorance of New Zealand conditions.

In the end Rome ruled in favour of Grimes. So he arrived in a Christchurch delighted to have its own bishop, but with many unhappy with his nationality and loyalties.

I do not intend to go into a long list of Grimes’ achievements as bishop in his 28 years. But I will highlight some of his successes.

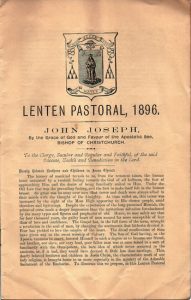

First of all, he worked hard at trying to unify his diocese. To this end, he convened the first diocesan synod in 1893, preparing all priests as well as he could for it. As well as frequent newsletters to all the clergy he wrote pastoral instructions to be read out in the churches every Lent. He made extensive visits to parishes, even the remote parts of Westland, being the first bishop to visit Jacksons Bay.

Another area in which he made huge contributions was education, bringing into the diocese the Mission and Mercy sisters as well as the Sacre Coeur nuns and the Marist Brothers, and providing accommodation for them all. The foundation for St Bede’s College in 1911 was his crowning achievement in this area.

His vision was wider yet, with the foundation of Mt Magdala for the rehabilitation of prostitutes; he brought in the Calvary sisters for nursing, as well as setting up the Marist Mission Band.

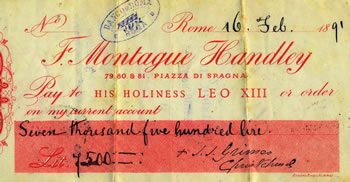

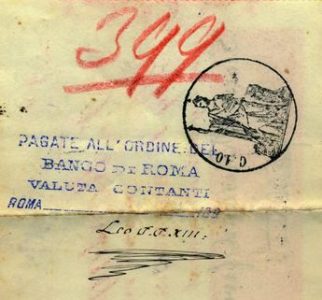

When he arrived the diocese was in poor financial shape. Through fund-raising lectures and tours, astute advertising and tight control of budgets, he was able to provide for the building of numerous parish churches. His supreme glory was, of course, the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, built between 1901-05. On completion it had cost £52,213; at the time of his death only a few hundred pounds remained to be paid off. The 1890s and early 1900s were tough times in New Zealand with recession and wide unemployment, especially on the West Coast. The bishop’s constant nagging of parish priests to keep on collecting the unpopular Cathedral tax irritated many of his clergy.

This was one area wherein Grimes struggled constantly. Rumblings of discontent from his diocesan clergy still continued; there was the continuing French versus Irish battle illustrated by the resignation of Fr Deby from Ahaura in April 1899, the French priest complaining that his position had become untenable because of the constant playing of the race card by his Irish curate, Fr King.

Then there were the gripes about money, that the Marists retained all the wealthy city parishes while secular priests had to man the small impoverished country parishes. Such complaints made it more and more difficult for the bishop to recruit newly ordained priests from Ireland. He was forced to accept men who struggled with alcohol and isolation. His attempts to bolster the diocese with other religious congregations such as the Sacred Heart Fathers from Australia merely resulted in more resentment from his diocesan priests.

Evaluating the Man and His Mission

In personality John Grimes could seem a bit remote and cold. He had few close friends and his address could be very formal. In his role of bishop he seems rather driven, sometimes a bit oppressive and demanding in matters of finance and planning. He inherited a diocese with significant problems, nor were his relations with the central Marist administration always cordial. Yet he achieved much and won wide respect from his fellow Cantabrians. And in the letters that he shared with his close friend and colleague Francis Redwood we see a warmth and sensitivity that signals the deep spirituality that allowed John Joseph Grimes to serve so well as the first bishop of the Diocese of Christchurch.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)

This was an interesting article but I was taken aback by Fr Vaney's comment, "His polemics were warmly received by many of the Irish rural labourers who arrived in large numbers under the premiership of Vogel, and who settled in areas such as Kerrytown, Timaru and Temuka." I would be interested to know what evidence Fr Vaney has to support this statement. I found quite the opposite to be true in analysing the Marist-Moran antipathy as it played out in South Canterbury in my book, Thinking About Heaven: a history of Sacred Heart parish Timaru. See "Chapter 6 Church Politics: Of Bishops, Priests and Mixed Loyalties". The book can be downloaded as a PDF in the web link I have given above.

Regards

Seán Brosnahan