Fr Antoine Garin in Auckland

On 14 April 2016 there was a Mass in honour of Fr Antoine Garin at St Michael’s in Remuera.

Anyone with Nelson connections knows of the saintly Marist priest who organised the building of many of the early churches at the top of the South Island, but what claim does Auckland have on him?

Antoine Marie Garin kept a series of diaries during his years in New Zealand. His entry for 14 April 1850, reads, ‘I say Mass for the last time in Panmure and Howick.’

Fr Christopher Skinner sm, performing a song he wrote in honour of Fr Garin, at the launch of Fr Garin's cause.

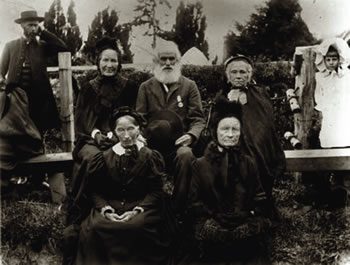

![]() Thirty-nine years later, 14 April 1889, was the day of his death in Nelson. Nelson and district were where he is most remembered, but the first ten years of his missionary work in New Zealand was in Northland and Auckland. Nelson has his grave, but the Bay of Islands, Wairoa and Auckland may lay claim to being where he did some of his best work.

Thirty-nine years later, 14 April 1889, was the day of his death in Nelson. Nelson and district were where he is most remembered, but the first ten years of his missionary work in New Zealand was in Northland and Auckland. Nelson has his grave, but the Bay of Islands, Wairoa and Auckland may lay claim to being where he did some of his best work.

So, who was Antoine Garin?

He was a Frenchman, born in 1810 in Saint-Rambert-en-Bugey, Ain, France.

He was a priest, ordained at age 24 for the Diocese of Belley by Bishop Devie.

He became a Marist four years later so he could be a missionary. He did his novitiate in Belley in 1838. He taught in a school for a year and then in 1840 set out for New Zealand. He was never to return to France.

On his arrival in Auckland, Bishop Pompallier appointed him as Provincial of the Marists working in New Zealand – an honour and a challenge, because Pompallier wanted Garin to concern himself only with their spiritual welfare, not where or with whom they were working. A year later he was put in charge of finances and supplies – Procurator to the Mission.

He was also a man who consistently kept a diary, filling multiple volumes with his detailed notes. Frustratingly, only some of these volumes have been preserved.

He described in a letter to Fr Colin what it was like going on a mission trip from the Mission Headquarters at Kororareka:

I travel from time to time through the various parts of the Bay of Islands. With a bit of bread and a little pork in a woven basket, I embark in the boat with two Brothers and out there we wander sometimes towards one tribe and sometimes towards another; if thirst overtakes us while we are eating our dry bread and salty pork, we soak this crust in the sea-water to slake our thirst; having arrived among the natives, we gratefully receive potatoes, kumara, fish or squash cooked on heated stones, then fitting to our mouths a little hole in a gourd which serves the natives as a bottle we moisten what we have chewed with a good drink of fresh water. When the meal has been finished, the bell announces the time for prayer, we worship God better than in the finest churches. Prayer is followed by a short instruction and the singing of some canticle or hymn about the main truths of religion. Already night has come. The Maori lights his pipe and leads us into the house which must shelter us during the night; a mat as thin as a sheet, spread on the ground, will serve us for a bed, our bags for pillows, and sometimes exhaustion leads to rest. Indeed you have to be a bit tired to sleep, because you are stifled by the smoke from the fire and the pipes and by the heat produced by the crush of a great number of people gathered together in so narrow a space. That’s not everything. Just when you are on the point of falling asleep, a great silence occurs: the chief has spoken, he has spoken to the priest: “Well now, priest, speak to us; come on, talk, talk.” And therefore it is better that you can instruct them there than in a church, because you have the whole night to spend talking to them. If the priest stops talking, the Maori goes on well into the night, day soon comes, and the missionary says: “I have to leave.” “But you are going to have prayers,” says the Maori, “and then, after you have eaten, you will leave.” There you have the life I lead, pretty usually, while waiting for someone to come and help me, but I groan at realising that I cannot stay at least a week in each tribe; that would be the only way of achieving some real good; at least you could instruct the children, you could teach reading and writing to these poor people who are so keen to learn.

If I go back to the Bishop’s house, it is to hear talk about accounts, debts, needs.

After three years working alongside Bishop Pompallier he moved out to a mission station on the Wairoa River in the Mangakahia valley. Initially at Hato Rohario – Holy Rosary. The mission station was not well set-up. From Garin’s diary it is clear that his cooking had to be done outside, and he wrote to his family that the house leaked, had no flooring and was apt to be invaded by the local dogs. However when Garin moved his station further down the river to a base near Tangiteroria which he called Hato Irene (St Irenaeus) he erected a sizeable house, a chapel, servant’s quarters, a small flour mill, a hectare of gardens, a chicken coop, a boat shed and a wine press!

Garin shared the Maori way of life: his everyday language was Maori, he lived with Maori assistants, he often slept under the stars or in Maori whare during his visits around his extensive circuit. Further, he genuinely enjoyed Maori company and built up significant friendships. Garin was willing to adopt everyday Maori practices, eating and appreciating Maori food, such as fermented corn, and using ti roots to slake his thirst during long journeys.

So Garin was a successful missionary to the Maori.

It must have come as a shock to him when, in 1847, he was appointed to work with Irish settlers in the Fencible Settlements of Auckland.

There had been war between settlers and Maori in the North of New Zealand, and the government had shifted from the Bay of Islands to Auckland, thereby putting up the price of housing. Governor Grey requested 2500 troops to defend the colony but 500 of those sent to him were retired rather than active troops and they were to be settled in villages south of Auckland to act in defence of the city. These were the Royal New Zealand Fencibles and they were settled in Panmure, Otahuhu and Howick. They had to attend military exercises twelve days each year and mustered for church parades every Sunday. Most of them were from Ireland. Governor Grey asked the Anglican and Catholic Bishops to provide chaplains, granted them an acre in each village for a church and presbytery, and they were permitted to purchase a further four acres of land as a glebe -- a small farm.

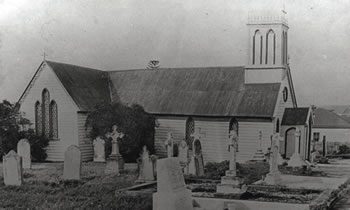

Garin, fluent in Maori, did not speak English very well. He considered the Irish to be more interested in drinking than in going to Church. However he quickly found that what his parishioners did want was an education for their children. Immediately he set about building schoolrooms that could act as temporary chapels while churches were built. The common project was strongly supported and united the communities in each of the villages. Garin soon had schools going in all three Fencible settlements – his one at Howick boasted that it had twice as many pupils as the nearby Anglican school. The Church of Our Lady Star of the Sea was opened in Howick in 1848, and he had ordered the timber for the Panmure church before his departure in 1850. After initial hesitation, Garin had won the heart of the parishioners of the Fencible parishes.

So, Garin was a successful Parish Priest.

His departure in 1850 was not of his own doing. There had been conflict between the Marist Founder, Fr Jean-Claude Colin and Bishop Pompallier. Colin acted as Pompallier’s agent in France, and Pompallier was in charge of the men sent to Western Oceania by Colin. Their disagreement was resolved by Rome deciding to create two dioceses in New Zealand, leaving Pompallier where he had been working, and sending the Marists to the newly created Wellington diocese.

Was Garin a saint? Many of his contemporaries thought so. Archbishop Redwood, a student of his, who conducted his funeral, declared, “He was indeed a saint, and attracted universal respect, and in many, sincere veneration.”

Given his life and deeds, I think I can safely say that if he did not get into heaven then most of the rest of us do not stand much chance.

The organisers of this event in Auckland wanted the sanctity of Garin to be acknowledged by the Universal Church. The very first step in that happening is for people to have a devotion to him, and offer prayers through his intercession.

If he is truly with God, which we believe, then such prayers will be effective. Expect miracles, and knowing the organisational abilities of Fr Garin expect them promptly.

One miracle, in particular, to pray for, is for an organisation in the Church to take up the cause of Antoine Garin.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)