Venerable Suzanne Aubert

by Rev Dr Ken Booth

This article was first published in Word & Worship,

Spring 2021, and is used with permission.

When Mother Marie-Joseph (Suzanne Aubert) died in Wellington in May 1926 at the age of 91, it was said that her funeral was the largest ever seen for a woman in New Zealand. This was a tribute to her indefatigable work in Wellington since 1899 and for years before that up the Whanganui River and in Hawke’s Bay.

Mother Aubert’s funeral procession, outside St Mary of the Angels church, Wellington

In Wellington, she and the Sisters of her Order worked with the poor and destitute. She opened a home for incurables in Buckle Street in 1890 and a day nursery for children in 1902 and then added a children’s home to the Buckle Street complex. The day nursery was an innovation and relieved the pressure on widows, abandoned mothers and those who had to work. In addition, there was a soup kitchen for unemployed people. In 1907, she opened the doors of Our Lady’s Home of Compassion for disabled and incurably ill children in Island Bay. Later, it included a surgical section and nursing training was incorporated.

State involvement on a large scale for social support in society began seriously in the 1930s. Before that most of it was done by charitable organisations and the churches. Children figure a lot in Mother Marie-Joseph’s work. Quite apart from unwanted pregnancies, many poorer families found the burden of one more mouth to feed too much to cope with.

Suzanne Aubert was born into a respectable middle-class family in a village near Lyon in France in 1835. She received an education in languages, music, literature and needlework. A serious accident at a young age and the death of her disabled brother left her with a profound love for those with disabilities. By the time she was sixteen she was convinced that she was called by God to join a religious nursing order. She went to Paris for nursing training and during the Crimean war served in the base hospital in France and on the hospital ships. She continued her medical studies in Lyon after the war, even though women were not allowed to graduate. She was still determined to become a nun. Her family was not pleased. Her mother had a suitable marriage lined up for her. Suzanne was not interested in marriage. Once she turned 25 she was free to take her own path. In the mid-nineteenth century to choose a religious course was a very real option, especially for women. Women had few chances of independence. Religious life offered the perfect avenue for Suzanne to exercise her considerable talents and her independence.

Sr Peata, with Mother Aubert seated on the right, and their pupils c. 1869

Her chance came in 1860 when Bishop Pompallier, a family friend, visited the area in a recruitment drive for his Auckland Diocese. Pompallier had baptised Suzanne in 1840. In Auckland, Suzanne began her religious novitiate in the Congregation of the Holy Family, with its house in Freeman’s Bay, Auckland. She took the name Sister Marie-Joseph. Marie-Joseph and the other French nuns were determined to work with Māori. They worked in the Māori Girls’ school in Ponsonby. Within a couple of years Marie-Joseph was fluent enough in te reo to be sent on mission work to Northland and the Waikato. In all things Māori her mentor was a fellow nun, (Hoki/Sister Peata), an influential and gifted relative of the powerful Ngāpuhi chief, Rewa. Bishop Pompallier returned to France in 1868, and the new Bishop, Thomas Croke, instructed Marie-Joseph to go home to France too. Bluntly she told the Bishop: “I have come here for the Māoris; I shall die in their midst. I will do what I like.” Feisty words, but totally in character.

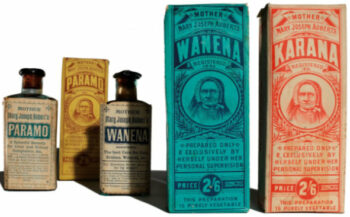

Marie-Joseph left the Order and moved to Napier in 1871, joining the Marist Order’s Hawke’s Bay Mission as a lay person. For the next twelve years she worked as district nurse for all who needed her. She drew no distinction between Māori and Pākehā, Catholic and anyone else. Her medical and nursing training stood her in good stead and she became very skilled at producing all sorts of remedies, many of them traditional Māori ones from native plants and herbs. She worked tirelessly. Records show that in 1873 she saw over a thousand patients. Māori loved her and called her Meri. Quite apart from her nursing skills she helped on the farm, gave religious instruction, led the local choir, played the organ and did embroidery.

Both in Hawke’s Bay and later in the community at Hiruhārama, Marie-Joseph wrote and translated material for the mission and the sisters. She revised and expanded the Māori Prayer book. This was published in 1879. She put together a Māori-English dictionary and a French-Māori phrase book. There was also a New and complete Manual of Māori Conversation in 1885, which included material on grammar and a large vocabulary. For her own Order she produced a compilation called The Directory.

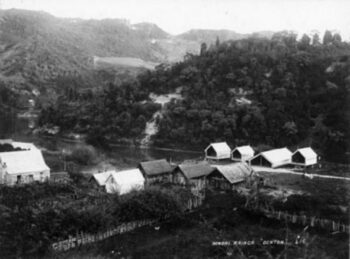

Hiruhārama – Jerusalem – early-1880s; some of Mother Aubert’s medicines

Archbishop Redwood of Wellington was very keen to re-open the Catholic mission up the Whanganui River at Hiruhārama (Jerusalem). The local Māori had been asking for a priest to help them after the wars of the 1860s virtually ended all work there. Bishop Redwood was to prove a stalwart supporter of Marie-Joseph’s work. In July 1883, Marie-Joseph and Fr Soulas, both from Hawke’s Bay, and three sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth settled in this impoverished community. Marie-Joseph promptly set about her work, encouraging the building of two schools and a dispensary for medicines. The community also offered a refuge for orphans and the chronically ill. All this was supported by work on the land and the sale of medicines downstream in Whanganui. The eventual move to Wellington in 1899 was in part brought about because Hiruhārama was just too far from medical assistance. Between 1891 and 1901, the community took in over 70 orphans from Wellington, many of them from unmarried mothers. In that period, to be an unmarried mother carried a huge social and financial burden. The fact that there were several infant deaths among the orphans may have hastened the move to Wellington.

Despite the success of the work, the Sisters of St Joseph withdrew in 1884, and it was decided that the best way forward was to establish a separate Order with Marie-Joseph at its head. It took a few years to achieve this but in 1892 the Daughters of our Lady of Compassion was formed. To have full independence and operate in its own way the Order would need papal approval. There were those within the Catholic hierarchy who found Marie-Joseph’s independence and autonomy a bit too much. To pursue her goals, Marie-Joseph went to Europe in 1913 to seek papal approval. While in Europe, she continued nursing throughout the First World War and did not return to New Zealand until 1920. By then she had received the papal approval of her Order and its work. It was granted in 1917.

It will come as no surprise in the light of this account that steps are under way to have Mother Marie-Joseph declared a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

The presence of God does not consist in thinking of God every now and then but in the consciousness of God’s presence in all our actions. Suzanne Aubert

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)