“Loving People Back to Life” — Caryll Houselander

Part 1 of 2

In early 1942, an amazing medical referral took place. Dr Eric Strauss, one of Great Britain’s most distinguished psychiatrists and neurologists, quietly began sending emotionally disturbed boys to spend time with a woman who was a spiritual writer, wood carver, poet, and mystic. Her name was Caryll Houselander.

This was a most curious triangle of relationships.

Firstly, there was Dr Eric Strauss, a distinguished and highly published British medical doctor who would become President of the Psychiatry Section of the Royal Society of Medicine and of the British Psychological Society.

Secondly, there was Caryll Houselander who had no formal training in either medicine or psychology. She had come to Dr. Strauss’ attention through her volunteer work at a school for boys who had been traumatised by the war, many of whom responded immediately and positively to her sensitive spirit.

Thirdly, there were the boys sent by Dr. Strauss to Caryll, all of whom were suffering from what today would be called Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome as a result of the war -- one boy, for example, had lived alone in the Malayan jungle after the murder of his parents.

These boys were sent to Caryll Houselander after all traditional medical and psychological therapies were ineffective. Under Caryll’s care and her intuitive application of music and art therapy as well as patient listening, the boys quickly recovered from their psychological scars and wounds. As word of her success with traumatised boys spread, other doctors began sending their adult patients.

Maisie Ward, Houselander’s biographer, interviewed Dr Strauss about the work Caryll had done for him. Strauss indicated he was so impressed with Caryll’s work with the boys that immediately after the war he unhesitatingly sent her adult patients for what he called ‘social therapy.’ Intrigued by the phrase, Ward said, “Forgive my dense ignorance, but what exactly is ‘social therapy’.” Without hesitation, Dr Strauss replied, “With Caryll, it meant she loved them back to life.”

Caryll Houselander (1901-1954) was a living paradox. On the one hand, she had a deep and profound spirituality which connected with an amazingly wide spectrum of people. On the other hand, she battled with a variety of issues. She was a chain smoker; was painfully shy; at times, seriously anorexic; often frail physically, she struggled with issues of abandonment, suffered from panic attacks and covered her face with a chalky white substance, giving her a grotesque appearance. Those were some of the reasons she was labelled ‘neurotic’ by some of her physicians. In fact, she considered herself damaged goods. One physician, however, was more complimentary and said she was not neurotic but highly sensitive. Because of her own trials and traumas, she was sensitised to the emotional and psychological wounds of others. This allowed her to connect in a deep way with suffering people. Through the 1940s and early 50s, Houselander emerged as one of Great Britain’s fascinating mystics and writers of spirituality. She wrote fifteen books and more than seven hundred poems, short stories and articles.

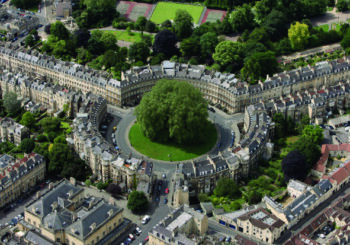

Born in 1901 in Bath, England, Houselander’s parents were Willmott and Gertrude Provis Houselander. Caryll was the second of two daughters. Her sister, Ruth, was four years older. The family, while not extremely wealthy, was financially prosperous enough to permit luxuries. They had a nurse and governess for the children; Willmott had time to become a skilled huntsman and Gertrude played tennis at Wimbledon. Their family structure began to change when Caryll was six. At that time Gertrude underwent a strong religious conversion to Catholicism. This created distance from her husband, who did not share her religious enthusiasm. The impact of her mother’s conversion was double-edged for Caryll. On the one hand, she felt that her mother’s prayers and practices were oppressive. There were long daily prayers, altars set up inside the home and frequent Mass attendance. Caryll referred to her mother’s religious orientation as a ‘persecution of piety.’ On the other hand, however, Caryll was deeply influenced by her mother’s devotion and would, over time, find herself drawn more and more to spirituality.

Eventually, Willmott, who could not accept his wife’s religious fervour, left the house, and the marriage ended in divorce when Caryll was eight. That event impacted Caryll harshly and it took years before she could properly integrate it into her life. In order to provide for herself and her daughters, Gertrude ran a boarding house. An opportunity emerged for the mother to send Caryll off to a convent boarding school when Caryll was eleven. Thus, in her short life, Caryll experienced parental abandonment twice: once when her father left, and again when her mother sent her away to a boarding school.

The Convent of the Holy Child boarding school located in a Birmingham suburb was run by French and Belgian nuns. One sister, however, was German and she was the one nun to whom Caryll became close. The sister was intuitively drawn to Caryll, probably because of the little girl’s sensitivity and loneliness. It is quite probable that the sister herself was a lonely woman. She was a German working with French sisters just as the First World War was to break out. Animosity between Germans and French was running high. Also, the sister spoke very little English or French and was thus somewhat isolated from the community.

One day, as Caryll walked by the room containing convent boots, she saw the German sister alone cleaning a pair of shoes. Caryll walked into the room intending to offer her help when she noticed that the sister was crying. “Tears were running down her rosy cheeks and falling onto the blue apron and the child’s shoes,” Caryll would later write in A Rocking Horse. Speechless and embarrassed, Caryll did not know what to say or do. They both remained silent for a few moments and then, Caryll experienced her first vision. She describes that moment this way:

“At last, with an effort, I raised my head, and then - I saw - the nun was crowned with the crown of thorns. I shall not attempt to explain this. I am simply telling the thing as I saw it. That bowed head was weighed under the crown of thorns. I stood for - I suppose - a few seconds, dumbfounded, and then, finding my tongue, I said to her ‘I would not cry, if I was wearing the crown of thorns like you are.’ She looked at me as if she were startled, and asked, ‘What do you mean?’ ‘I don’t know,’ I said, and at the time, I did not. I sat down beside her, and together we polished the shoes.”

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)