The Martyrs of Široki Brijeg

7 February 2020 was no ordinary day in Široki Brijeg, Bosnia Herzegovina. The Franciscan friars and townspeople gathered at the Church of the Assumption to commemorate one of the most atrocious massacres in the history of Bosnia Herzegovina. Seventy-five years had passed since thirty monks were slaughtered there on 7 February 1945.

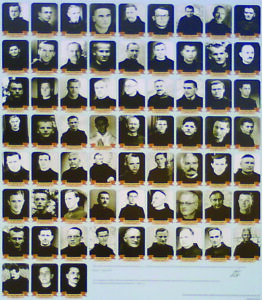

Inside the Franciscan church at Široki Brijeg, on the right-hand side, is a tomb built as a consequence of the massacre of sixty-five friars. The remains of twenty-four are buried in this tomb.

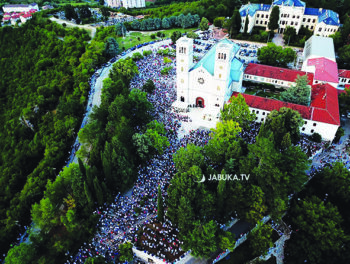

Široki Brijeg means ‘a wide hill’. It is about an hour’s drive, forty km, from Medjugorje, Bosnia, and eighty-eight km from the Adriatric coast. The town has a population of 13,000 people. Široki Brijeg is 270 metres above sea level and a large part of the surrounding countryside is mountainous. The town was labelled a pro-fascist region during the Second World War and was demonised by Yugoslavia and renamed Listica, after a river in Bosnia Herzegovina. For anyone who wants to understand the Catholic culture and the history of Bosnia Herzegovina, Široki Brijeg is the place to visit.

Bosnia Herzegovina was predominantly a Catholic country until the Turkish occupation in 1463. For many years the Turkish occupiers destroyed churches and monasteries, especially in Široki Brijeg. When tensions had eased in the area and calmness descended on Bosnia, the Franciscans built a monastery and church at Široki Brijeg in 1846. The Franciscans, founded in 1209 by St Francis of Assisi, bought a plot of land and constructed a church dedicated to the Mother of God. They also built roads and bridges and, in the course of time, introduced electricity to the area. They built a seminary and a famous comprehensive school which was a recognised seat of learning and scholastic achievement. That is why the monastery and church of Široki Brijeg, which are located on the high ground that overlooks the town, are synonymous with the Franciscans. This spacious and well-constructed church, which adjoins the monastery, is of an architectural design that would be hard to surpass.

These days, the area may be a picture of peace and tranquility, but it was not always so. The Ustashe – Ustasa – was a fascist, terrorist organisation founded in 1929 that terrorised and brutalised thousands of Serbs, Jews and political dissidents during the Second World War. Their policies were expressions of Nazi racial ideology. The Ustasa was strongly Roman Catholic and claimed Catholicism as the religion of the Croats. They succeeded in forming a national state, but many ordinary Croats did not support them because of the brutality for which they were renowned.

Between 1942 and 1945, sixty-five Franciscan friars were murdered in Bosnia Herzegovina and of these, thirty were from Široki Brijeg monastery community, with another four from the surrounding monastery area. The soldiers also destroyed the friary. In the course of their destruction, they wiped away the names of God, along with a dedication to the Assumption of the Mother of God, from the main entrance to the friary, and burnt the monastery.

The reign of terror commenced on 20 May 1942, when Fr Stjepan Natetilic was taken from his home and shot near the village of Zanaglina Kupres. Between October 1944 and March 1945, another six monks were murdered in Bosnia. Murders continued in Mostar, historically the capital of Herzegovina, and in other towns and villages until May 1945.

On the morning of 7 February 1945, the communists arrived and killed thirty friars and monks. The soldiers proclaimed: “God is dead, there is no God, there is no pope, there is no church, there is no need of you, you also go out in the world and work”. The communists then asked the friars to remove their habits, but they refused. One soldier took the crucifix and threw it on the floor, saying “you can now choose either life or death”. Then each of the friars knelt and embraced the crucifix, saying, “You are my God and my all”. The friars were taken outside and shot through the head. The soldiers then poured gasoline on twelve of them and burnt their bodies in the war shelter near the monastery garden. Not long after, in an effort to destroy all vestiges of Catholicism, the communists set fire to the church and seminary. Today, outside the war shelter, there is a commemorative plaque to the thirty who were executed.

It is recorded that one of the soldiers in the firing squad that day later uttered the words:

Since I was a child, in my family I had always heard from my mother that God exists. To the contrary, Stalin, Tito, Lenin had always asserted and taught each one of us: there is no God. God does not exist. But when I stood in front of the martyrs of Siroki Brijeg and I saw how those friars faced death, praying and blessing their persecutors, asking God [to] forgive the faults of their executioners, it was then that I recalled in my own mind the words of my mother and I thought that my mother was right: God exists!

But the testimony of this soldier did not end there. He became a Catholic and today he has a son a priest and a daughter a nun.

The thirty Franciscans from Široki Brijeg are surely a testimony in declaring themselves for Jesus. As Jesus says in the gospel, “Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; fear him who can destroy both body and soul in hell”.

The oldest monk to die was Fr Marko Barbaric, who was eighty, having been born on 19 January 1865. He had a reputation for sanctity among the seminarians. He had lost his memory during the Second World War. On 7 February, he was in his room and ill with typhus (an infectious disease that causes headache, fever, rash and general malaise). The communists ordered him from the room. He was shot and burnt. The youngest was Brother Louis Rados, who was twenty, born 14 November 1925, and who had recently finished his novitiate.

A week later, the communists killed another seven friars in Mostar, three of whom were from the parish of Medjugorje. In 1933, these three friars helped in the construction of the Cross, which commemorates the passion and death of Jesus. Known as Cross Mountain, it is 33 feet high and the highest mountain region in Medjugorje.

The 1940s saw ferocious fighting between the Ustase and the communist Partisans under Tito, who governed Yugoslavia until he died in 1980. After the war, the communists endeavoured to separate children from their national identity and faith. Bosnia Herzegovina was neglected and many were, for economic reasons, forced to leave the district. But the more the communists tried to crush the religious beliefs of these people, the more devout they became, and many joined religious communities.

From November 1942, the provincial, Fr Kresimir Pandzic, directed that a record be kept of those friars and monks who were subjected to atrocities. A certain calm prevailed until 1971 when the provincial at the time again directed that witnesses provide whatever evidence they could about the circumstances leading to the deaths. It was not until the fall of communism in 1989 that more systematic work commenced on the circumstances surrounding the atrocities in Bosnia Herzegovina

The Catholic church supported the Ustasa and many Franciscan monks were accused of war crimes. The slain Franciscans were not involved in any form of armed conflict, despite the repeated declarations of Franciscans “with guns in [their] hands”. They offered no resistance and were the victims of unspeakable atrocities.

In 1971, a hundred Franciscans defended the reputation of their slain brothers. They testified to the innocence of their slain colleagues, emphasising that they were not in any conceivable way organisers or leaders of armed resistance.

The Franciscans at Široki Brijeg are determined that the Church should declare these monks martyrs and saints. The Martyredom Procedure Vicepostulature Committee in Široki Brijeg is led by Fr Leo Petrovic and sixty-five other assistants. This committee collects evidence from witnesses about the atrocities between 1942 and 1945, and anyone with any information is asked to contact them.

These monks died for their faith; people in Široki Brijeg and beyond who may have experienced abundant graces and concessions in their lives are urged to contact the Vicepostulature.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)