Of Choice and of Discernment

By Fr Brian Cummings SM

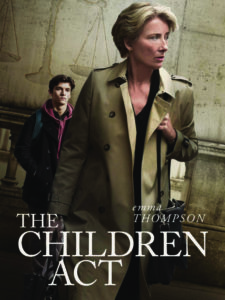

Prayerful Reflection with the movie The Children Act

If the movie Of Gods and Men (2010) illustrates perfectly what is meant by ‘group discernment’, then The Children Act (2018) can be said to illustrate perfectly how ‘choice’ on a personal level is not necessarily discernment.

Before getting into what is missing from The Children Act in terms of discernment, though, let’s focus on what is there – or more accurately, who is there: Emma Thompson.

And here I have to admit to a personal bias. I will watch anything that Emma Thompson is in because I believe she is, without question, one of the leading actors currently in movies.

It remains one of life’s frustrations for me that one of her greatest performances (in Wit (2001)) did not receive the recognition due to it because the film was released straight to HBO rather than to the regular cinema circuit.

However, receiving two Academy Awards and being made a Dame Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (the equivalent of a knighthood) does indicate the standing that Emma Thompson is held in and that any movie she is involved with deserves close attention.

And when that movie is an adaptation of one of leading author Ian McEwan’s books then there is added reason to take it seriously.

The Children Act is essentially a movie of choices – and those choices largely revolve around British High Court Judge Fiona Maye (Emma Thompson) and her professional and private lives.

Fiona Maye sits on the bench of the Family Division and is a highly respected and well-regarded judge. She knows the law thoroughly and she knows how to apply it properly.

The movie (directed by Richard Eyre) begins with a graphic demonstration of her ability and acute legal mind as she rules on a much-publicised case involving a Catholic family where the question is whether conjoined twins should be separated (resulting in the death of one of them).

The parents say “No” because of their faith; others say “Yes” on the principle that it is better that one baby live than both die. Not surprisingly, Fiona rules in favour of separation – because that is what the law and The Children Act, brought in by Parliament, says should happen.

The situation is, ultimately, decided by logic and what is the law, rather than by the personal beliefs of the parents (or of Fiona, for that matter).

But while law and logic might work (and be required) in court, it is not necessarily the same on the personal level for Fiona.

Another major choice presented in the movie involves the relationship between Fiona and her husband, Jack (Stanley Tucci).

He complains bitterly that their relationship has become totally subordinated to Fiona’s work and announces his desire to have an affair with a younger member of his faculty. The ‘choice’ is not entirely his alone – he does ask Fiona for her permission to have an affair. In his own mind, he wishes to treat his wife with respect and keep an open relationship between them, while at the same time being seemingly totally oblivious to the enormous pressure Fiona is under (and she, too, is oblivious to what is happening to her marriage because of her absolute focus on her court cases).

And while this unravelling of their relationship is going on, Fiona is presented with another major case: that of a 17 year old son of a Jehovah Witness family who urgently needs a blood transfusion to survive leukemia. The son, Adam (Fionn Whitehead) and his family are clear and definite on their religious obligations and rejection of any blood transfusion. Fiona becomes involved only because Adam is just short of his 18th birthday (and so still under The Children Act).

Again, Fiona makes a choice – this time (and highly unusually) to visit Adam in hospital. Although done with the best of intentions – to get to know Adam as a person – things spiral rapidly out of control, both for Fiona and for Adam.

It is a complicated movie and a very compelling one to watch, posing “sophisticated questions around family, religion, marriage, law and the delicate boundaries that can or cannot be crossed in each institution” (Tomris Laffly, Roger Ebert, September 14, 2018).

It is also a movie about choices rather than about discernment, for all the evident religious threads in it.

As was noted in the Reflection on Of Gods and Men in the Spring 2019 issue of Today’s Marists, “A decision is not necessarily a deliberate, self-conscious choice, and it does not necessarily occur in the context of prayer. Discernment does both. With discernment, we enter into a dialogue with God after establishing a right relationship” [The Gift of Spiritual Intimacy, Novalis Books, p160].

The Children Act is full of major choices. In the case of Fiona, the choices are made against a background of learning, experience and awareness of the legal parameters within which she has to work. In the case of Jack, the major choice he makes (and soon regrets) arises out of frustration, desire and a sense of urgency that his options in life are rapidly closing in. And in the case of Adam, his choices emerge through a mixture – and a conflict – of religious upbringing, personal beliefs and personal desires.

All of these choices are significant; all are life-changing; all are made (or at least begin) as deliberate and self-conscious.

What they are not is discernment in action.

How do we distinguish between ‘a choice’ and ‘a discernment’?

Perhaps the key distinction lies in how the choice is arrived at.

As we’ve seen, in The Children Act choices are consciously made – either because of personal desire or because of awareness and knowledge of what is appropriate in this situation (even if that can become quickly blurred as the consequences of initial choices begin to make themselves evident).

In discernment, there is also a ‘consciousness’ – but it is focussed more on how a choice is arrived at, rather than primarily on what the actual choice is.

There is an underlying awareness and acceptance that ‘my choice’ is not simply and solely my choice. That the choices I make on major decisions are not solely the outcome of my learning, my desires, my environment.

Rather, there is an overt awareness that my choices arise out of my relationship with God. And if that is the case, then what is involved in this ‘relationship with God’?

There are a number of key elements, including the following ...

Self-Belief: a belief that God loves me as I am with all my good points and all my weaknesses.

An Awareness of Others: we do not try to live a self-contained, isolated life but recognise that we belong to different groups or ‘communities’ – family, parish, work, religious community – and that we are enriched by them, and have obligations to them.

Awareness of Our Emotions and Our Intellect: we live out of both our intellect and our heart, not just one or the other.

Understanding the movements in our spiritual life: “In Ignatian terms, we talk about spiritual consolation and spiritual desolation. How we understand spiritual consolation and spiritual desolation depends on whether our basic orientation is towards intimacy with God or away from that intimacy. Consolation and desolation are not feelings. They are indicators of the direction in which we are pointed based on our underlying attitude”(cf Monty Williams, The Gift of Spiritual Intimacy, pp28-29).

Our Desired Grace: we develop a sensitivity to and awareness of “what do I need God to do in my life at this time?”

Knowing our Deepest Desire: we seek in prayer and reflection to deepen our understanding of what most fundamentally motivates us? What determines why I get out of bed each day? What am I trying to achieve in my life?

Ultimately, whether we are watching Of Gods and Men or The Children Act, from a Marist perspective there is an added question to be asked – one that fundamentally underpins and gives context to all our actions, our choices, our discernments: “Is what we are doing in the spirit of Mary?”

This article first appeared the 2019 Fall issue of Today’s Marists, a publication of the USA Province of the Society of Mary.

Fr Brian Cummings SM is the Director of Pā Maria Marist Spirituality Centre, Wellington, New Zealand

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)