Blessed Franz Jägerstätter

Tricia O’Donnell

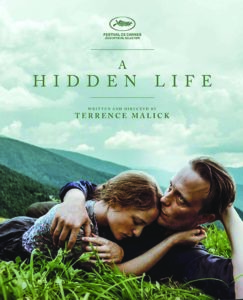

On the 19 May 2019, a film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. It was about a conscientious objector who was executed by the Nazis in 1943. ‘A Hidden Life’ recounts the story of Austrian Franz Jägerstätter, a 36-year-old Catholic whose refusal to fight led to his eventually being declared a martyr.

He was born Franz Huber, on 20 May 1907, the illegitimate son of a chambermaid, Rosalie Huber. His grandmother virtually raised him, as his parents were too poor to marry. His natural father was then killed in World War One, and when he was 10 years old, his mother married a farmer, Heinrich Jägerstätter, who formally adopted him. As a young man, Franz loved sport, music and reading but he had a slight rebellious streak and joined a local motorcycle gang. He did a stint as a farmhand before leaving home to work in the mines.

By the time he returned home in 1933, after inheriting the farm from his stepfather, he had practically abandoned the faith he grew up with and later that year became father to a baby girl after an affair with a village girl. There was no question of marriage, due to his mother’s opposition, though he adored his daughter and remained in her life until his death. This event turned his life around and he began to return to his faith. Three years later, he married Franziska Schwaninger, a devout Catholic, who further encouraged him in his spiritual life. They left immediately after the ceremony on a pilgrimage to Rome. Three daughters were born to the couple between 1937 and 1940.

The 1930s were permeated with the threat of war in Europe. “Re-union of Austria with the German Reich” – Hitler’s term -- left the Church in no doubt that it would have to bow to his demands. Threats of destruction of all the convents were made should the Church not agree, and by the time Hitler invaded Austria in 1938, Franz had already decided he wanted nothing to do with Nazi rule. While the bishops of Austria agreed to the new rules, hoping this would ensure the safety of the Church, Franz refused, though his local priest voted “yes” on behalf of the parish. Nevertheless, Franz was determined to distance himself from the rulings and refused the office of mayor in his village. His anti-Nazi stance was well known among his neighbours, who had no time for the new regime either, but would not openly disobey for fear of reprisals. They did, however, support him, and when he was called up for military service in May 1940, the mayor spoke up for him, insisting he was needed to run his farm. In October of that year he was again called up, and insisted that he wanted to experience army life for a while, though when it came to his discharge in April 1941, he was in no doubt where his loyalties lay.

Franziska and Franz Jägerstätter, married on Holy Thursday 1936

For Franz, being unable to attend Mass or practise his Catholic Faith was bad enough, and the more he learnt of Nazi atrocities, the more difficult he found it to conform to their rule. He consulted several priests and even travelled to Linz to talk to the bishop, who advised him to reconsider his stance and to think of his family.

Scene from ‘A Hidden Life’

Disheartened, he knew in his heart that he would not serve in the military. When he again received his call up papers in February 1943, he reported to the authorities in Enns, Austria, and his refusal to serve resulted in his arrest and imprisonment in Linz. Although he stated he was prepared to enlist in the medical corps, this was denied, so he was left with no option but to face the consequences of following his conscience.

Franz’s determination to do this did not stop people trying to convince him otherwise. His wife eventually gave up trying and accepted his decision. She said if she hadn’t stood by him he would not have had anyone. His lawyer pointed out that other Catholics were serving to which he replied, “I can only act on my own conscience. I do not judge anyone, I can only judge myself”.

On 4 May 1943, he was transferred to Berlin where he remained until his hearing on 6 July at the supreme military court. All further attempts to encourage him to change his mind failed – his local parish priest concluded that “as a Catholic, he could not take up arms, because it would mean fighting for National Socialism, and he could not in conscience do that. At this, he had to be sentenced to death”. On the 14 July, he was officially sentenced and on 9 August 1943, Franz Jägerstätter was executed. He was 36 years old.

Grief was not the only thing his young widow had to endure. Franziska said that while “other women mourned as widows”, she was treated like her “husband’s murderer”. For many people, especially those in the military, Franz’s duty as husband and father should have been his priority and their antagonism towards him flowed through to her. It would be 1950 before she was granted a widow’s pension, and only then because he was deemed to be mentally ill for using religious belief as a reason for refusing to join the military.

Scene from ‘A Hidden Life’

Franziska Jägerstätter attended her husband’s beatification ceremony at St Mary’s Cathedral in Linz, Austria, in 2007. She died in 2013, two weeks after her 100th birthday.

Blessed Franz Jägerstätter Pray for us

The prison chaplain, Father Kreutzberg, continued to help Franziska long after the war was over. “You can be sure”, he wrote, “that not many in Germany have died as your husband did. He died a hero, a confessor, a martyr and a saint”. Pope Benedict XVI declared Jägerstätter a martyr in June 2007 and in October of that year he was beatified in a ceremony in Linz. His feast day is 21 May, the day of his christening.

Until 1964, Franz Jägerstätter was relatively unknown to the world. His biography In Solitary Witness, by Gordon Zahn, was released that year, and since then much has been written about him, as well as documentaries and movies. Throughout the world, his story continues to be told – and it’s an inspirational story that transcends all earthly bonds. Shortly before his death he wrote that, “Neither prison nor chains nor sentence of death, can rob a man of his faith and his free will. God gives so much strength that it is possible to bear any suffering … People worry about the obligations of conscience as they concern my wife and children. But I cannot believe that, just because one has a wife and children, a man is free to offend God”.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)