A Short History of the Marist Brothers

Part 2 of 4

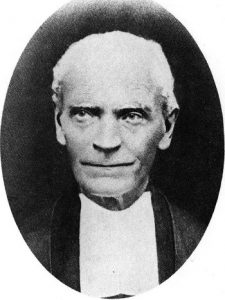

In 1896, our Founder, Fr Marcellin Champagnat, was declared Venerable, Fr Chanel having been beatified in 1889. By this time, teaching brothers had been present in the Pacific for some twenty-five years and in New Zealand for twenty. The congregation was in a state of rapid expansion. Just three years had passed since the visit of another Superior General, Br Théophane Durand, in 1893.

Théophane had already visited Canada, Spain and North Africa. One of the reasons for these visitations was to find suitable sanctuaries for the brothers now coming under increasing pressure in France from anti-clerical governments. In fact, in only seven years’ time, in 1903, all the teaching congregations would be suppressed and expelled from France. Over 500 establishments would be closed and a quarter of the brothers in France lost to the congregation. On the other hand, the numbers leaving the country were sufficient for the creation of four new provinces overseas, including one centred on Australia, and New Zealand, Samoa and Fiji would become a province in 1917.

All these new communities followed the Hermitage model. The brothers lived a monastic lifestyle, centred on the schools. Government was highly centralised, with authority being vested in the Asssistant General responsible for the province rather than the Provincial superior himself. Since all matters of importance had to be referred to him, one can imagine that this caused a certain amount of frustration for the Provincial of Australia, for example, where an exchange of correspondence might take longer than six months. While reforms in 1903 gave the local superior somewhat more responsibility, it was still the Asssistant General who had the most say in the running of the province.

The schools were mainly primary, some having a Civil Service class to prevent students having to move to a state secondary school. A little high school was opened in Auckland in the early 1890s, in Pitt Street, which became Sacred Heart College when moved to a new site in 1903.

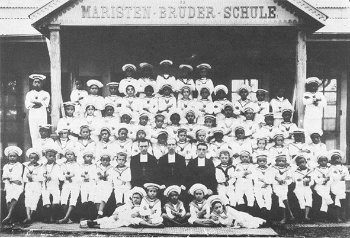

The brothers had also taken charge of an orphanage, St Mary’s, at Stoke near Nelson, which they would conduct from 1890 to 1900. They ran a little juniorate at Napier from 1899 to 1903, and even a short-lived novitiate in Samoa, at Moamoa, from 1910. In Fiji, the segregated educational system set up by British colonial authorities required separate schools for Europeans, Fijians, Indians and other ethnic groups. And in Samoa, the partitioning of the country in 1900 meant two separate education systems to adapt to, German and American.

What characterised the communities, at least up to the First World War, was their international composition: French, Irish, English, Scots, Germans, Belgians, Swiss, an Italian, even a Luxembourger, joining the Australian and New Zealand graduates of the novitiate in Australia. Before 1903, when this part of the Marist world formed part of the Province of Great Britain and the Isles, brothers came from, and sometimes returned to, South Africa, New Caledonia and the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), as well as Europe. The director of the first community in Wellington, Br Sigismond, a Frenchman, went on to South Africa. The first teaching brothers in Samoa, Brs Ulbert and Landry, both French, died in New Caledonia. Another French brother, Philippe-Beniti, having worked in New Zealand, Fiji and Samoa, joined the China mission. One of the German brothers in Samoa, Frederick Henry, came to the Pacific after some years in Brazil, and another, Gerard Meister, after teaching in all parts of the province, was later Director of Education in the Seychelles. In 1889, the Provincial, B

r John Dullea, had to explain to his Asssistant General why it was difficult for him and his council to establish a dietary regime in keeping with the Rule that satisfied the mixture of French, Irish, English, Scottish, Australian and New Zealand brothers in the Australian communities. Fortunately, this seems to have been the only problem, apart from national attitudes to sport, to disturb the harmony of community life. French and German brothers in Samoa during the war appear to have lived, worked and prayed together without much difficulty.

The brothers did, however, face problems in getting themselves established in the Pacific. In New Zealand there was a strong secular lobby which made its mark on the education system the very year the brothers arrived to open schools (“free, secular and compulsory”).

Sectarianism was widespread and sometimes rabid, and there was considerable anti-Irish as well as anti-Catholic prejudice. Within the Catholic community itself, they were caught, in the early days, in the tension between a French Marist clergy and a largely nationalist Irish laity. Samoa suffered from intermittent civil war and then colonial partitioning. In Fiji, there was strong Protestant opposition to the mission schools and difficulties with the colonial administration.

For a striking illustration, we need look no further than the orphanage at Stoke, the largest of the communities in New Zealand and the Islands in the last decade of the 19th century. Here we had a typical community of the period – French, Belgian, Irish, New Zealand and Australian – in a Marist parish, running what, since 1880, had been re-defined as an industrial school, something close to the Social Welfare Boys’ Homes of the 1970s, and with the same problems.

The reports of the Provincials of the period detail the progress of both staff and students, praising improvements in discipline, classwork, religious practice and living conditions, and criticising sometimes harsh punishments and deficiencies in administration. In his report to the Superior General in April 1900, the Director, Br Loetus, painted a glowing picture: a flourishing farm, students engaged in cultivating commercial crops and experimenting with growing vines, exam passes as good as those in the state schools, a school band and a proposed cadet corps, and most former students going on to become good citizens and good Catholics. But were the brothers to be commended for this? They were not.

This same year, there was a resurgence of anti-Catholic feeling stirred up by the Irish Protestant Orange Lodge, and when two runaways in May were found and returned to Stoke via the courts, rumours spread that their punishment would be too severe.

Such was the state of local opinion that the government was obliged to set up a Royal Commission to inquire into the running of the school. Its findings did little more than confirm the criticisms made by the Provincials over the decade and were clearly not damning enough for the bigots, who then levelled charges of assault against two of the brothers. These charges were dismissed one by one during a three-week trial, and the two were discharged without conviction. But the reputation of the institution and the brothers had been tarnished and some of the provisions of the new Bill introduced into parliament as a result of the enquiry made it impossible for the brothers to continue at Stoke. They were withdrawn in September. Thus, a very promising project was brought to an abrupt end through bigotry, opportunism and political cynicism. Sad to say, the ‘Stoke Affair’ was still being cited, for much the same reasons, as recently as the 1990s.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)