Fr Jeremiah O’Reily OFMCap –

- and the Early Catholic History of Wellington

Part 4 of 4

Fr O’Reily was an excellent writer, with an appetite for debate. He engaged in robust, but generally good-humoured, argument with Protestant writers in the colony’s newspapers. Papers of the day were prepared to publish remarkably sophisticated and extended correspondence. Topics O’Reily debated ranged from the use of candles in the liturgy, and the nature of the Eucharist, to the existence of the legendary Pope Joan. He gently chided a particularly belligerent correspondent, writing, “The intervention of Sunday may… give rise to more hallowed feelings in ireful bosoms”.

Fr O’Reily also prepared a compilation of prayers and statements of Church teaching which he published in 1844 as “St Mary’s Catechism”, and dedicated it to “the citizens of Port Nicholson… [and] the congregation of St Mary’s”.

However, most of his pastoral work was done out in the community. Colonial Wellington was a tough town, with poor roads and sanitation, and high rates of alcoholism and infectious disease. Fr O’Reily was well known for offering spiritual, and sometimes material, support to any who needed it, regardless of their religious affiliation. He made regular visits to the town gaol, at the corner of The Terrace and Abel Smith Street, and acted as chaplain to the 65th regiment when it was stationed in Wellington during the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s.

Although, as his published debates demonstrate, he was a staunch defender of Catholic doctrine, Fr O’Reily was in many ways a pioneer in ecumenical relations. He was held in such high regard by the Elders of St John’s, a Presbyterian church on Willis Street, that on one occasion he was asked to lead a service, strictly according to Presbyterian norms, when no minister was available.

Although the modern parish of St Mary of the Angels can trace its history back to Wellington’s beginnings, it was not until 1874 that the first church bearing the name was erected.

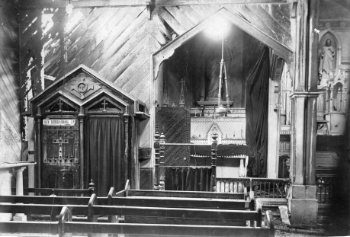

By 1873 the old chapel had stood for thirty years, and survived two major earthquakes. As the need for a replacement became pressing, Fr O’Reily devoted himself to the project. In 1867 he made an extended trip to Europe to raise funds, and by 1873 construction was underway. The new church was in the gothic style, but constructed entirely of wood. A contemporary newspaper noted that due to lack of funds the church was rather plain and unadorned, but provision had been made in the plans to allow for additions to be made as money became available.

With a seating capacity of 450, and plans in place for an extension, the architect’s estimated cost of £1500 was exceeded by only £30. The blessing of the church took place on 27 April 1874, the name ‘St Mary of the Angels’ being taken from a church in Assisi, birthplace of St Francis. St Mary of the Angels stood for just 44 years before burning down in 1918. The current church was built on the same site.

When he arrived in New Zealand in 1843 Fr O’Reily was “delighted to find some of my poor countrymen from Erin’s most distant shores”. The Church in Wellington, and in New Zealand as a whole, took on an increasingly Irish character as the years went by.

In the early 1840s there were fewer than 250 Catholics in Wellington, and virtually all the priests in New Zealand were French Marists. By the time of O’Reily’s old age, there were several thousand Catholic Wellingtonians, many of them, including the writer’s ancestors, Irish.

In 1874 when Bishop Redwood appointed an Irish Marist to serve as assistant priest at St Mary’s, the long association between the parish and the Society of Mary began.

Fr O’Reily finally retired as parish priest in 1878. His successor, Fr Kerrigan was the first of many Marists who would lead the parish. Te Aro / St Mary of the Angels was granted in perpetuity to the Society of Mary in 1883.

In retirement, Fr O’Reily took up residence near the church, where he spent his time in prayer. He was by now well-known to Catholic and non-Catholic alike, and stories exemplifying his dedication entered Wellington folklore. It was told, whether apocryphal or not, that he fell into a muddy ditch on a night visit to Newtown and was found the next day by the milkman, placidly saying his rosary. He died, as historian Michael King put it, “full of years and honour”.

A Requiem Mass was said by Fr McNamara at St Mary of the Angels on Boulcott Street. The church was filled to capacity and a great crowd had gathered outside. The text Fr McNamara preached from could not have been more appropriate -- “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith” (2 Timothy 4:7).

After the Mass, the funeral procession made its way down Willis Street and Lambton Quay, then up the Terrace until it reached Mount Street cemetery perched above the harbour, near the site of the humble presbytery Fr O’Reily had walked up to countless times. A cross bearer flanked by altar boys led the way, followed by several hundred children from the Marist and Convent schools. A dozen altar boys and five priests walked with the coffin. The Evening Post recorded the most moving fact, that thousands of Wellingtonians of all denominations and faiths accompanied Fr O’Reily on this journey. It is hard to imagine a scene of public religious devotion on such a scale in Wellington today. And indeed, it was not to everyone’s taste. Protestant writer Charlotte Godley noted disapprovingly that the procession looked like “something out of France or Italy”.

Three years later when a public subscription was taken to raise a 10 foot Celtic Cross above his grave, former Governor George Grey remarked “... put up your monument; it will decay and fall to pieces… but the good he has done will not pass away”.

The fine wooden church that Fr O’Reily raised in 1874 was lost to fire in 1918, and no trace of his presbytery on Mount Street remains. But his legacy is the Church as the Body of Christ in Wellington, which will endure.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)