Abba Father — Who Are You? (4)

Shame at the Service of Love

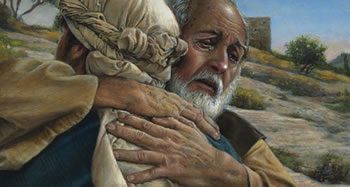

Chapter 15 of Luke’s Gospel is very familiar; variously described as the Prodigal Son, the Loving Father, the Lost Son and Brother. At the story’s centre is the unexpected, even disarming spontaneity of the father’s reaction to the son he sees, in the distance, coming back home. This graphic scene presents another feature of the God revealed to Moses and later embodied in Jesus, one who is always for us, with us, on our side, taking the long view.

What does this parable suggest to us about Abba Father? It might help to consider the story from the father’s perspective and, specifically, from within the world in which the parable is set. In a culture such as ours, with a greater sense of the individual, the central moral category is guilt.

Here, the family and cultural background is Mediterranean, one where shame and honour play a significant role in shaping attitudes and guiding behaviour. In many cultures today, this is still the case; perhaps we have something to learn here.

First, there is the younger son’s request for his share of the estate. While, strictly speaking, he would receive his share once his father had died, his request has a callous tone, suggesting to his father and the local village that, in his eyes, his father is “as good as dead” (Byrne, 129).

This would be a cause of shame for any family, and the shame would be deepened on the son’s return, after squandering all his inheritance. The son would not have anything to fulfil his filial obligation to support his father in his old age; all the more pressing given the father’s diminished resources.

Second, there is the shame associated with the son’s gradual decline – socially, financially and religiously. He is so desperate that he resorts to feeding pigs, both degrading and unimaginable for Jews. This one detail has symbolic weight -- the son has rejected his religious and family heritage. He has become a Gentile.

In these two areas, the father rises above his culture and its expectations. In public, with compassionate responsiveness and forgiveness, he spontaneously reaches out to this son who has betrayed his heritage and brought shame and dishonour on his father and the family. The father, no doubt, would be very conscious of what the neighbours and relatives would be thinking. But he does not hide his face in shame or let himself be paralysed from acting.

He rises above all that. He is “moved with pity” – the same Greek word used earlier to describe the Good Samaritan’s reaction on seeing the wounded traveller (Luke 10: 33). The father orders a celebratory banquet. He bestows a ceremonial robe, shoes and signet ring -- symbols of those who have the status of a free person (Byrne, 129).

Rather than just a family affair, others in the wider family and village would be encouraged to come with him in his, and his wife’s, joy. At the same time, it was also an invitation to share the loving father’s way of seeing life; one where forgiveness and love overrides shame.

Here, shame is owned, claimed and transformed, hence, directed to a higher, more constructive purpose. Would the others accept the invitation? We don’t know if the older brother finally joined the feast; perhaps his struggle was about still being locked into, and paralysed by, his shame...??

Thirdly, the father’s sense of rising above his culture’s restraints is captured in these words: “he ran to the boy, clasped him in his arms and kissed him tenderly”. Brendan Byrne’s comments are helpful here:

We modern readers have to understand that this is totally unconventional behaviour for a dignified man of affairs in the Palestinian cultural world. To leave the house to meet one of lower rank, to run rather than walk sedately, to display emotion extravagantly in public: all this involves serious loss of face and dignity (129-130).

Again, the father’s behaviour is reflected in Jesus’ own freedom in relation to Israel’s customs. We see this in the incident of the woman in the crowd who touched Jesus and was healed. In this, Jesus challenges what it means to be ‘clean’ or ‘unclean’.

He redefines them in terms of what is truly life-giving and grounded in one’s relationship with God rather than in social or religious custom that excludes and divides a person and a community. Here, the father does the same in terms of shame and forgiveness.

On a broader scale, suggested in this parable, we can detect later the divine family DNA at work concerning shame.

Let us not lose sight of Jesus, who leads us in our faith and brings it to perfection; for the sake of the joy which was still in the future, he endured the cross, disregarding the shamefulness of it… (Heb. 12:2).

Indeed, shame at the service of love.

Reference: Brendan Byrne, The Hospitality of God (Strathfield, NSW: St Pauls, 2006).

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)