Indulgences

Fr Merv Duffy SM

A much-debated question in theology is how much a person can work towards their own salvation. Are they merely the passive recipient of God’s grace – is it all God at work? Do they earn their place in heaven – is it all them at work? The answer in the Catholic tradition is between those two extremes. “According to Catholic understanding, good works, made possible by grace and the working of the Holy Spirit, contribute to growth in grace, so that the righteousness that comes from God is preserved and communion with Christ is deepened” (Joint Declaration on Justification, 38). By the gift and grace of God we are able to do good works that help us to get holier, to get closer to God.

We can compare this with how an ordinary human love relationship grows. It depends on the free actions of both parties. You can woo someone, but you cannot force them to love you. When a husband spontaneously buys flowers for his wife his act expresses his love and hopefully strengthens their relationship but it does not compel affection. The lover and the beloved are both free. Their love grows in response to each other’s free gift of themselves.

Modern theology understands the grace of God and our good works as operating in terms of this kind of free gift-exchange. Through divine providence God is wooing us, and every loving response we make opens us more to the relationship God is offering. God’s grace does not force us, we can refuse it, put an obstacle in its path. Our good works do not force God to love us more or to justify us.

Good works benefit us because God freely chooses to reward them. When we act justly, pray sincerely, or do an act of kindness we grow closer to God. Evil actions have the opposite effect. Every sin erects a barrier between us and the grace God freely offers. Sin has consequences, it affects us. Good deeds act against the effects of sin. Our free choices matter, virtue takes us towards God, vice takes us away.

In the early days of the church, confession and penances were public. There is a fascinating example detailed by the Bishops of the Council of Nicea back in 325 AD:

Those who have been called by grace, have given evidence of first fervour and have cast off their [military] belts, and afterwards have run back like dogs to their own vomit, so that some have even paid money and recovered their military status by bribes - such persons shall spend ten years as prostrators after a period of three years as hearers. In every case, however, their disposition and the nature of their penitence should be examined. For those who through their fear and tears and perseverance and good works give evidence of their conversion by deeds and not by outward show, when they have completed their appointed term as hearers, may properly take part in the prayers, and the bishop is competent to decide even more favourably in their regard. (Canon 12 of the Council of Nicea).

To understand this very early canon law you have to realise that there was a time when army service involved worshipping the standard of the legion, a pagan idol. Military service and Christian faith were incompatible, so soldiers who became Christian left the army. The Bishops are considering the case of someone who lapsed from their Christian faith and re-joined the army only to change their mind again and want to come back into the Church.

Hearers, Prostrators and Pray-ers

In the Church at the time of Nicea, the congregation was divided into different groups who stood in different places during the mass: the Hearers who were allowed to hear the liturgy of the word and then had to depart; the Prostrators who, after the liturgy of the word, received a blessing from the president, for which they prostrated themselves, and then left; the Pray-ers who remain through the Eucharistic Prayer; and those who received communion. Your status in the church was evident from where you stood. Those ex-soldiers who had given up on the faith to go back to the army were to stay on the fringe of the congregation for at least thirteen years before they were allowed to receive communion.

History of Indulgences

This system of public penances established two ideas among the Catholic faithful. That you can measure the punishment due to sin in terms of time and that the bishop and good works can shorten this time. This became known as granting an “indulgence”.

When confessions ceased to be public and penances became private the “punishment due to sin” was thought of as time in Purgatory rather than public penance during the liturgy. We have no idea how time works in Purgatory but it is when all the consequences of sin are purified. Hence a virtuous deed could be thought of as reducing the amount of time to be spent in Purgatory.

Making a pilgrimage to a holy place was clearly a good work. A bishop could increase the number of pilgrims to his Cathedral or shrine by declaring that, for example, a visit there would take ten-years off the time you were due to spend in Purgatory.

Such indulgences were very popular but there were problems with just who was authorised to grant them and a tendency to “inflation” – why not grant an indulgence of 110 years rather than merely 10?

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was attempting to counter this tendency when it taught the following:

Moreover, because the keys of the church are brought into contempt and satisfaction through penance loses its force through indiscriminate and excessive indulgences, which certain prelates of churches do not fear to grant, we therefore decree that when a basilica is dedicated, the indulgence shall not be for more than one year, …(Lateran IV, Canon 62)

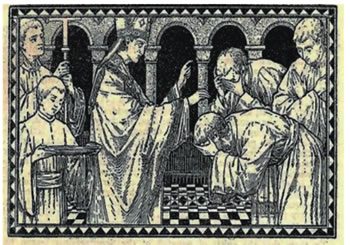

A woodcut depicting the selling of indulgences c 1510

Simony

Helping to build a church was evident virtue. Giving money to enable a church to be built is obviously a related good act and indulgences were granted to people who contributed. However, this looks like a commercial transaction; hand over money and receive an indulgence in return. Because of the story in the Acts of the Apostles about Simon Magus trying to buy the gift of calling down the Holy Spirit by the laying on of hands (Acts 8:9–24), the church has long considered the selling of sacred things to be the sin of simony.

Council of Trent

This was the issue that sparked the Protestant Reformation just over 500 years ago. The Augustinian Friar, Martin Luther, wanted to debate with the Dominican fundraiser and indulgence preacher, Johann Tetzel, when he proposed 95 debate-topics in Wittenberg in 1517. Most of his proposed topics were to do with indulgences. Many people in the church were very critical of the whole notion of indulgences.

In 1562 the Council of Trent endeavoured to addresses abuses associated with indulgences and reserved the publication of indulgences to the bishop of a diocese. In 1567 Pope Pius V cancelled any grants of indulgences that involved fees or a financial transaction.

Paul VI

Paul VI

In 1967, in an apostolic constitution called Indulgentiarum Doctrina, Pope Paul VI again addressed the doctrine and practice of indulgences. He ended the practice of assigning a number of days to an indulgence – indulgences are now simply either partial or plenary. He makes it clear that “indulgences cannot be acquired without a sincere conversion of mentality ("metanoia") and unity with God.” He considerably reduced the number of plenary indulgences. “Real” or “local” indulgences were abolished “to make it clearer that indulgences are attached to the actions performed by the faithful and not to objects or places which are but the occasion for the acquisition of the indulgences.”

We can see that Pope Paul VI was trying to bring the practice of indulgences back into the realm of actions of love. He wanted the Christian faithful to pray, to fast, to act justly so as to express their love of the Lord and their growth in holiness.

Enchiridion

Enchiridion

The first indulgences described in the Enchiridion, the official book of norms on Indulgences:

A partial indulgence is granted to the Christian faithful who, while performing their duties and enduring the difficulties of life, raise their minds in humble trust to God and make, at least mentally, some pious invocation.

So praying brings a Christian closer to God. So do works of charity:

A partial indulgence is granted to the Christian faithful who, prompted by a spirit of faith, devote themselves or their goods in compassionate service to their brothers and sisters in need.

And so does fasting and the exercise of self-restraint:

A partial indulgence is granted to the Christian faithful who, in a spirit of penitence, voluntarily abstain from something which is licit for and pleasing to them.

Plenary indulgences can be gained by doing the ordinary deeds of a good Christian life:

- adoration of the Blessed Sacrament for at least one half hour (no. 3);

- devout reading of the Sacred Scriptures for at least one half hour (no. 50);

- the devout performance of the Stations of the Cross (no. 63);

- the recitation of the Marian Rosary in a church or oratory, with members of the family, in a religious Community, or in a pious association (no. 48).

A plenary indulgence can be gained only once a day. In order to obtain it, the faithful must, in addition to being in the state of grace:

- have the interior disposition of complete detachment from sin, even venial sin;

- have sacramentally confessed their sins;

- receive the Holy Eucharist (it is certainly better to receive it while participating in Mass, but for the indulgence only Holy Communion is required);

- pray for the intentions of the Supreme Pontiff. (Any prayer, though an Our Father and a Hail Mary are suggested).

Indulgences have a very long history in the Church. They have encouraged virtuous actions and helped many people on their path to salvation. Thanks to Pope Pius V, they are no longer something to be bought or sold. Because of Pope Paul VI, indulgences are a simple and concrete support and encouragement for practices that should be part of the life of every Catholic.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)