A School for Prayer (14)

By Fr Craig Larkin sm, 1943 - 2015

The Desert Experience

Sinai -

John Climacus and prayer of the heart

From Egypt to Sinai

From Egypt to Sinai

The great flourishing of the Desert period in Egypt was to last only about 100 years.

Though remnants of this period in Egypt would remain through the centuries (and still remain to this day), nevertheless, by the end of the 5th century many monks had moved from Egypt.

1) By this time there had been three generations of monks in the desert of Egypt.

The general tone of fervor had slackened. Macarius had foretold that this would happen.

Thirteenth century

icon of St. John Climacus; to either side are Saint George and Saint Blaise (Novgorod School) wikipedia.org.

2) During the 5th century three terrible destructions of monasteries had been carried out by Barbarians: in AD 407, 434, and 444. Monasteries were destroyed and monks were killed. The desert of Egypt was no longer a safe and tranquil place of solitude. Abba Poemen witnessed the first destruction in 407, and began his work of collecting the Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

When you see a cell built close to the marsh, know that the devastation of Scetis is near; when you see trees, know that it is at the doors; and when you see young boys, take up your sheep-skins and go away. Macarius 5

3) At the Council of Alexandria in 400, and later at the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, Origen’s writings were condemned as heretical. A great controversy erupted among the monks of the desert, involving persecution. Many monks, desiring a life of contemplation, moved away from Egypt.

Palestine, Gaza, and especially Mount Sinai, became new points of reference for monastic life in the East.

Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai was an obvious place to establish monasteries:

• Sinai was the site of the wells of Jethro;

• It was associated with the childhood and youth of Moses;

• It was the site of the Burning Bush;

• On Mt Sinai God revealed himself to Moses;

• In the Desert of Sinai, the People of God made their Exodus;

• In Sinai the People revealed their infidelity to God, while God showed his fidelity to them.

Sinai was more isolated than Egypt. It was a dangerous place where the monk was stripped of all self-sufficiency. In this place of isolation only God could sustain the monk and preserve him from harm or madness.

Soon hermitages, monasteries and settlements sprang up in the desert of Sinai. Archeologists have discovered 550 monastic sites dating from the 4th century.

A new expression of Spirituality

In the previous centuries – in the Desert of Egypt – a question that monks asked was “In what part of the person does prayer actually take place?”

All agreed that prayer took place in the ‘soul’ of the person: but what part of the ‘soul’? In the mind? In the heart? In the memory? In the imagination?

Macarius – the heart

Macarius – the heart

‘Macarius’ (considered to be Macarius of Egypt) wrote of prayer as a matter of the ‘heart’; his spirituality is centred on a passionate relationship with Jesus. Prayer is an expression of human desire. His approach is experiential.

Evagrius – the mind

Evagrius of Pontus taught that prayer took place in the nous or the intellect. But although prayer was something in the mind, it was not an activity of the mind. In fact, the mind was to be emptied of all activity – especially memory and imagination - during prayer. His approach is intellectual.

Diadochus of Photike -

Mind-in-the-heart

Another writer – Diadochus of Photikē – makes a synthesis of these two contrasting approaches. He speaks of prayer as “mind-in-the-heart.”

Another writer – Diadochus of Photikē – makes a synthesis of these two contrasting approaches. He speaks of prayer as “mind-in-the-heart.”

A new form of spirituality develops during this Sinai period. It will lead to what subsequent centuries developed as ‘the prayer of the heart’, ‘monologistic prayer’ (one-word prayer). It is associated especially with ‘hesychastic prayer’and the ‘Jesus Prayer’ of the Russian, Greek and Eastern tradition.

The first significant traces of this spirituality are expressed by one of the great personalities of the Sinai tradition: John Climacus.

John Climacus

John Climacus is recognised as a saint by the Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholic, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Church. Hardly anything is known of him – even his dates of birth and death are unclear. He probably lived between 579 and 649.

John Climacus came to stay at the Monastery of St Catherine when he was 16 years old. He stayed there until he was 35 years old. He then retired into the desert and lived in a cave for 40 years.

When he was about 75 years old, he was persuaded to return to the Monastery of St Catherine and become the Superior (Igumen) of the monastery.

When he was Abbot of the Monastery, he was asked by Abbot John of the monastery of Raithou to write a text on prayer and the spiritual life for his monks.

Reluctantly, John Climacus agreed.

He shaped his work around the image of a ladder reaching to heaven, calling his book ‘The Ladder of Divine Ascent.’

For this reason he is known as John ‘Climacus’ – (Klimax [Greek] = Ladder)

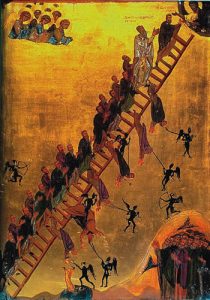

Climacus’ image of the ladder caught on powerfully. It became the subject of many icons, the oldest and most famous being kept in the monastery of St Catherine on Sinai.

Monks are depicted at different stages of their journey on the ladder. John Climacus stands in the bottom right corner, indicating the Ladder that the monk must climb.

“The Ladder of Divine Ascent” is the most published, translated and quoted book of spiritual guidance in the Eastern Church.

It is read every Lent in all monasteries of the Eastern Church, and in many monasteries of the Western Church.

he 12th century Ladder

of Divine Ascent icon (Saint Catherine's Monastery, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt) showing monks, led by John Climacus, ascending the ladder to Jesus, at the top right wikipedia.org.

“The Ladder of Divine Ascent”

The book describes the journey of the monk to God in thirty steps of a ladder.

The Chapters divide themselves into three sections:

1. Breaking with the world (Steps 1-3)

2. Practicing the virtues and struggling with the passions (Steps 4-26)

3. Finding union with God (Steps 27-30)

John did not intend that his image of the ladder should be interpreted too literally. Even though they are described in ordered sequence, the different steps are not to be regarded as strictly consecutive stages.

John’s style

John’s style of writing is unique. He is obviously a sharp observer of people; he shows a keen sense of humour; and he writes in a colourful way:

On the need to take one’s spiritual life seriously:

“The man who takes up a spiritual life and at the same time seeks an easy life is like someone trying at the same time to swim and to clap his hands.”

On the need for spiritual direction:

“It is not safe for an untried solider to leave the ranks and take up single combat.”

On controlling one’s appetites:

“The man who thinks he can control his spirit of lust while at the same time eating and drinking too much is like someone who tries to quench fire with oil.”

On being watchful:

“When a man fights a lion, it is fatal to glance away for even a moment.”

“The vigilant monk is a fisher of thoughts, and in the quiet of the night he can easily observe and catch them.”

On the spirit of greed:

“A man whose legs are bound cannot walk freely. Those who hoard treasures cannot climb to heaven.”

“Waves never leave the sea. Anger and gloom never leave the person who is greedy.”

On Acedia:

“The lazy monk is wide awake when talking to his friends, but half asleep when it is time for prayer.”

On how virtues and vices can exist together:

“When we draw water from a well, it can happen that we inadvertently also bring up a frog. In the same way, when we acquire virtues we can sometimes find ourselves cultivating vices which are imperceptibly interwoven with them. Practicing hospitality can sometimes produce gluttony; practicing love can sometimes produce lust, and so on.”

On how living in community can bring good results:

“A solitary horse can often imagine itself to be running at full gallop, but when it finds itself in a herd it then discovers how slow it actually is.”

On the difficulties of living in community:

“When a harbour is full of ships it is easy for them to bang against each other, particularly if they are secretly riddled by the worm of bad temper.”

On studying the mysteries of God:

“It is risky to swim in one’s clothes. Likewise a slave of passion should not dabble in theology.”

John Climacus’ teaching on Prayer

With regard to prayer, John Climacus gives no instructions regarding outward practices such as fasting, posture, or formulas. He offers no techniques, but he offers guidelines for the path of prayer.

Consider the following:

1. The way you pray tells you how you stand with God.

2. Do not move into prayer without preparation.

3. The time of prayer is not the time to be thinking of your plans and projects, or even to be thinking of spiritual things, but of meeting God.

4. If you have suffered wrong at the hands of others, forgive them. Otherwise prayer will be of no benefit to you.

5. The first step is to clear your mind of thoughts; the second is to concentrate on what you are doing; the third step brings pure joy.

6. Pray simply. Both the prodigal son and the tax collector were reconciled by a single short phrase. And don’t be over-complicated. The lisping and stammering of a child was heard by God.

7. Don’t talk too much when you pray. Talkative prayer leads to fantasy; short prayer makes for concentration.

8. If during prayer some word or phrase strikes you, linger over it.

9. Do not think that your attempts at prayer have gained you nothing. Being in the presence of God you have already achieved something.

10. “You cannot learn to see just because someone tells you to do so. In the same way you cannot discover the beauty of prayer from the teachings of others. You need to experience it for yourself. God will teach you your prayer.

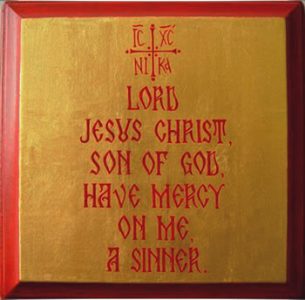

Prayer of the heart - The Jesus Prayer

Above all, John Climacus lays the foundation for what would become the ‘Prayer of the Heart’.

Above all, John Climacus lays the foundation for what would become the ‘Prayer of the Heart’.

He suggests that we should take a simple phrase, or a word, or simply the name of Jesus, and let it remain in our head, constantly repeating the word or phrase.

Then by connecting the word or phrase or the name of Jesus to our breathing, we bring the prayer down into our heart.

Let the remembrance of Jesus be present with your every breath. Then indeed you will appreciate the value of stillness (Step 27).

This way of praying has its dangers and difficulties, and should only be undertaken under the guidance of a director or spiritual father.

This is the basis for what was later developed as “Hesychastic” prayer (Hesychia = stillness), a way of praying that has been common in the Church of the East, particularly on Mt Athos in Greece, and in Russia.

The “Jesus Prayer” grew out of this tradition.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)