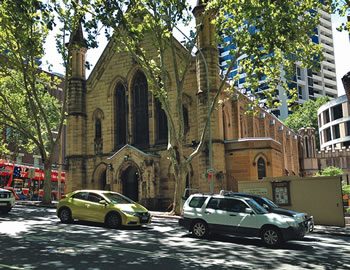

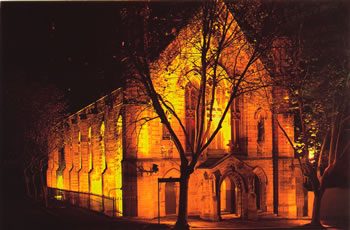

St Patrick’s Church, Sydney

Introduction

Fr Michael Whelan SM

In May 1818, Fr Jeremiah O’Flynn left the consecrated host with lay-Catholics in Sydney when he was deported. In 1868, St Patrick’s, Sydney was entrusted to the Society of Mary. Along with bishops from around Australia, the Most Reverend Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher OP, will celebrate the noon Mass at St Patrick’s on 6 May, the date on which Fr O’Flynn left the host; and on 16 September, marking the Marist sesquicentenary in the parish.

Where the story begins

The late Patrick O’Farrell begins his remarkable history of the Catholic Church in Australia with the following quotation from the first Catholic Vicar-General, William Ullathorne, in 1833:

We have taken a vast portion of God’s earth, and made it a cesspool; we have poured down scum upon scum and dregs upon dregs of the offscourings of mankind and we are building up with them a nation of crime, to be … a curse and a plague … 1

O’Farrell then observes:

O’Farrell then observes:

Australian Catholicism was born in this cesspool, the religion of prisoners. Its twisted, shackled inheritance is epitomised in the circumstances of the first recorded Mass, which was celebrated for a congregation of prisoners in Sydney in May 1803, under strict regulations drafted by Governor King and with police surveillance, by an Irish convict priest, transported – by mistake, it seems – for alleged complicity in the 1798 Irish rebellion. 2

The convict priest was Fr Dixon. O’Farrell continues:

This cautious toleration of Catholic worship had come fifteen years after the colony’s foundation. It was withdrawn in panic the following year and, although Dixon, and after him Fr Harold, exercised their ministry in a private capacity, it was not until 1820, another sixteen years, that Mass could be celebrated publicly again. 3

Govenor Lachlan Macquarie

In fact a lively bit of our history emerged just before the two priests – Therry and Connolly – arrived in May 1820: the Irish Cistercian priest, Jeremiah O’Flynn, arrived without any official authorisation from England in November 1817. He went to Governor Lachlan Macquarie to request his permission to minister to the 6,000 or so Catholics in the colony, telling the Governor that his credentials from the Colonial Office would be coming with the next ship. O’Flynn was allowed to remain until the position could be clarified, but he was not permitted to engage in any public ministry. O’Flynn did not observe the restriction on his ministry, going about baptising, celebrating marriages and Masses at which

Catholics assembled, with or without leave of their overseers. 4

O’Flynn was deported by Governor Macquarie in May of 1818.

Before he left the colony, it is believed that O’Flynn left the Blessed Sacrament with the Catholic community. The precise date on which O’Flynn celebrated his final Mass is uncertain. It is also believed that in November 1819, the Blessed Sacrament was consumed by the chaplain of a visiting French ship.

The preservation of the Blessed Sacrament

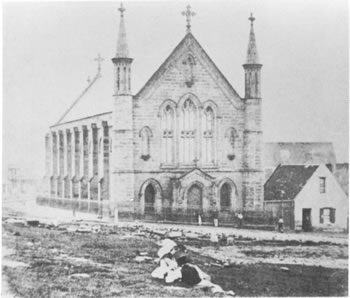

On Tuesday 25 August 1840, the foundation stone of the second Catholic church in Sydney Town, dedicated to St Patrick, was laid and blessed by Bishop John Bede Polding. The bishop

mounted a large stone and pointed dramatically to a nearby cottage. ‘See that cottage! There twenty years ago was our religion cradled and concealed – there its mysteries worshipped’ 5

It is assumed that Polding was referring to the home of William Davis. Davis had donated the land for the church, next door to his home where Fr O’Flynn had stayed and celebrated Mass more than twenty years earlier. This gave rise to the belief – still strongly held today – that the Blessed Sacrament was preserved in the Davis cottage after O’Flynn left.

It is assumed that Polding was referring to the home of William Davis. Davis had donated the land for the church, next door to his home where Fr O’Flynn had stayed and celebrated Mass more than twenty years earlier. This gave rise to the belief – still strongly held today – that the Blessed Sacrament was preserved in the Davis cottage after O’Flynn left.

O’Flynn’s pyx, in which the Blessed Sacrament was held, was retained by the Davis family. Through Sister Gertrude Davis, it came into the possession of the Sisters of Charity at Potts Point, where it may be seen to this day.

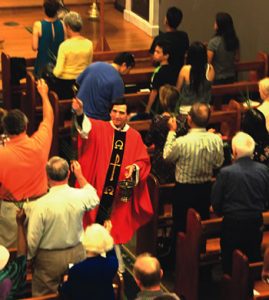

Fr Paul Hachey SM blessing palms at St Patrick’s

The belief that the Blessed Sacrament had been preserved at the Davis cottage was called into question when, in 1865, it was claimed that Fr O’Flynn also celebrated Mass in the home of the James Dempsey family and left the Blessed Sacrament there. The Dempsey house was about five minutes walk from the Davis house, near the intersection of Erskine and Kent Streets. Fr McMurrich writes:

The claims for Dempsey were first made in print in 1865 by Columbus Fitzpatrick, who stated that as a child, he had observed the Sacrament being venerated in Dempsey’s house; his version of events was later corroborated by his younger brother, Ambrose.” 6

Patrick O’Farrell comes down firmly on the side of the Dempsey version. However, in his book, Challenge: The Marists in Colonial Australia, published ten years after O’Farrell’s book – John Hosie probably gets it right:

While it is impossible to be conclusive, both homes lie in the St Patrick’s Parish and there is no doubt the church was intended to commemorate the event. 7

1 Patrick O’Farrell, The Catholic Church and Community in Australia: A History, Nelson, 1977, 1

2 Ibid.

3 Op Cit, 1-2

4 Op Cit, 13

5 Fr Peter McMurrich SM,

The Harmonizing Influence of Religion: St Patrick’s Church Hill, 1840 to the Present, published by Patrick Books, 2011/2017, 9.

6 ibid., page 10

7 Footnote 26, page 287

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)