Judaism in New Zealand

Orthodox and Progressive

by Juliet Palmer

Rabbi Yitzchak Mizrahi

As with Christian denominations, a range of Jewish religious movements have emerged over the years.

Until the 19th century, Jews were simply “Jews”: the observances were uniformly the same. However, after some Jews redefined themselves as “Conservative”, “Reconstructionist” and “Reform”, for example, Jews who adhered to traditional observance were labelled “Orthodox”.

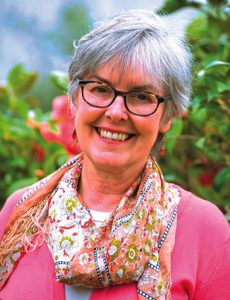

In New Zealand there are two denominations – Orthodox and Progressive. Rabbi Yitzchak Mizrahi (Orthodox) and Rabbi JoEllen Duckor (Progressive) shared some of the similarities and differences between their ways of observing their faith.

An obvious difference between Orthodox and Progressive Jews involves gender.

Rabbi JoEllen Duckor

“Holding a ministerial position titled ‘Rabbi’ is limited to men [in the Orthodox faith] – though 90 percent of the functions – such as teaching or counselling – can be performed by women and men,” Mizrahi says.

He explains Orthodoxy has a very specific belief system.

Firstly – belief in God is fundamental.

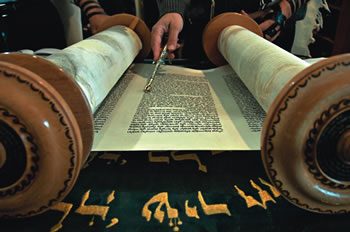

Secondly – Orthodox Jews accept the Torah was divinely given and the text was transcribed by Moses. It is unalterable: every Torah scroll is a carbon copy of the original scroll Moses transcribed.

Thirdly – Orthodox Jews believe in the oral traditions that were given along with the Torah text.

“In this sense, the written text is a skeleton that needs the complement of the interpretation/explanation. The Talmudic literature is the written form of all the oral forms that are part and parcel of the written Torah,” Mizrahi says.

“Furthermore, the Torah includes all the laws for living – it is the written law qualified by the oral Talmudic law.

“Every advancement of civilisation and technology needs to be filtered through the timeless rules and values expressed in the Torah and Talmud.”

Torah reading in a synagogue with a hand holding a silver pointer

In essence, any changes need to fit within existing Torah laws and values, rather than submitting the Torah laws to the changing world, Mizrahi explains.

“Nonetheless, the various streams of Judaism all fall under the same cultural umbrella.

“In practice, the observances of festivals and events might differ, but generally we observe the same lifecycle events, festivals and occasions.”

The Tefilin, secured to one arm

and to the head with straps, aims to achieve a spiritual alignment of the heart, mind and body.

Lifecycle events include: circumcision for boys on the eighth day after their birth; Bar Mitzvah (boys), Bat Mitzvah (girls) – where they are considered religious adults; marriage; funerals.

The two communities also celebrate the same high holidays: Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashannah, Festival of the Tabernacles, Passover, Pentecost (renewal of commitment to receiving the Torah and studying the Word) plus the Rabbinic festivals of Hannukah and Purim.

Both communities observe five fast days when there is no eating or drinking from daybreak until nightfall: Ninth Av, 17 Tamuz, Fast of Gedaliah, Ten Tevet and the Fast of Esther. The first four are “mournful” fasts – mourning the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temples, plus other calamities that have befallen Jews. The Fast of Esther is not a mournful fast.

They also observe Yom Kippur: a 25 hour fast of atonement, beginning at sunset and ending the following nightfall.

Children are not obliged to fast and dispensations can be sought: the cardinal rule, Mizrahi says is if fasting endangers health or life, you don’t fast.

While both communities have similar views and observe in similar ways, there are some distinct differences in interpretation, Duckor says.

“We like to say ‘there’s more than one way of being Jewish’: there are many acceptable Jewish practices, much more individual interpretation of the laws.”

Duckor offers the kosher laws as an example – that is, what the law says you may or may not eat or mix.

“We do follow the law, but we have our own interpretation of the laws too. For instance, many people observe what is known as ‘eco-kosher’ – that it is not kosher to eat caged-reared food. Nor is it kosher to eat food contaminated by plant sprays.

“Progressive Judaism is more in tune with the modern world,” she says.

Examples she offers include women’s rights. Women have been graduating as doctors and lawyers for many years, she notes – “so since the 1970’s we’ve also become rabbis.

“In this way Progressive Judaism is a more inclusive observance.

“We accept all sexuality without distinction. Progressive congregations have gay, bi and transgender members and rabbis.”

Nonetheless, Duckor acknowledges all congregations are different – some are more conservative than others.

“The Progessive world is more diverse than the Orthodox, which tends to be the same everywhere.

“But we use the same prayer books and scriptures.

“However, we observe the Commandments with the view that ‘the past has a vote but not a veto’: we look at our traditions and the world around us and try to adapt.

“It’s not a lesser, watered down or ‘easier’ way to practise – we engage in a lot of questioning about what things mean. We keep kosher because it’s meaningful for us.”

Duckor says a Jewish person can be a member of any congregation.

“We are all Jews. One of the reasons people break away from Orthodoxy in New Zealand is because they marry a non-Jewish person: it’s hard to find a Jewish spouse here – and Orthodoxy doesn’t accept marriages between people who are not both Jews.

“Another reason is because not everyone wants to practise in the Orthodox way.

Our services are in both English and Hebrew. We sit together and pray, while men and women are separated in the Orthodox Synagogue.

“Essentially, we have the same rules, but individuals can choose how observant they are. In my private life I am very observant – for instance, I walk to the Temple on the Sabbath, but others drive. We think it’s more important that you come to the services than to pay attention to how you get there.”

Duckor thinks people in both Orthodox and Progressive communities probably have similar levels of observance.

“Deciding which community they belong to is more about where the individual feels they belong and fit best,” she says.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)