Who Are You, Jesus? – 4. God who shares in our humanity

Fr Tom Ryan

We continue an earlier discussion on how Jesus identified, not only with victims, but with all of us in our weakness, struggles and failures.

We share the divine life through the Holy Spirit ‘living in us.’ The other side to that is the mystery of God in Jesus who partakes in our humanity. Paul says of Jesus that “in his body lives the fullness of divinity” (Colossians 2:9).

The scope of this gesture whereby Jesus “did not cling to his equality with God” (Philippians 2:6) is developed further by Paul in words that may, initially, startle us: “for our sake God made the sinless one into sin” (2 Corintians 5:21). What does Paul mean?

Sharing our fallen humanity?

Clearly, Paul isn’t saying that God made Jesus a sinner or that the divine and sin were somehow compatible. They aren’t. It is rather that Jesus, in his incarnation, represents all sinners. Further, in some way, he experienced in himself and his life the effects of sin. He shared in our ‘fallen’ condition, though clearly not through guilt or in moral corruption in any form.

The Gospels witness to those effects: He was hungry, thirsty, rejected, hated, was afraid, died and, even, in some mysterious way, felt what it was like to be separated from his Abba Father. Elsewhere, we hear of Jesus as the compassionate High Priest who can “sympathize with those who are ignorant or uncertain because he too lives in the limitations of weakness” (Hebrews 5:2).

Again, the same letter confirms what Paul says above: “we have one who has been tempted in every way that we are, though he is without sin” (Hebrews 4:15). Jesus, the sinless one, shared in human freedom, and, at times, in the reverberations of ‘sin,’ by being ‘tempted’ or ‘tested.’ Let’s consider this.

Decisions, Decisions…

Baptism of Christ,

Cima da Conegliano 1893-4,

San Giovanni in Bragora, Venice

Jesus, at times, found himself caught between alternatives. He was forced to make a choice, not necessarily between good and evil, but between two goods or values. For instance, between the claims of God and of his parents or his family (Mark 19:35; Luke 2:41-51); or situations where his life was at risk and he had to choose between self-preservation and not deviating from his mission (Luke 13:31; John 11:8); and in Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-42). Interestingly, Jesus’ ministry commences with two mini-dramas that put into action the words of Hebrews above.

Firstly, the Baptism scene. Under the Spirit’s impulse, Jesus is drawn to be baptised by John in the Jordan. Through being receptive to God’s action, Jesus is willingly included among struggling humanity. Perhaps, Jesus felt himself carrying the burden of sin, not because of any disordered choice. It was rather as “the effect of his total solidarity with sinful humanity,” something similar to guilt by association (Casey, 30).

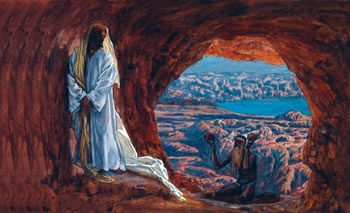

Second, Jesus, was ‘driven’ by the Spirit into the wilderness, and was tempted there by the devil for forty days. Perhaps, Jesus felt drawn to take time and create space to reflect on the experience of being fully loved by his Abba/Father in the Baptism event at the Jordan.

What actually happened, no doubt, came as a surprise. Rather than being overwhelmed with gratitude and renewed receptivity, Jesus finds resistance rising to the surface. “Within the microcosm of his own psyche, Jesus experienced the encounter of the prodigal Father and his errant child” (Casey, 49).

The temptations are subtle, resembling opportunities for Jesus to make compromises so that his mission would be ‘less burdensome’ but, perhaps, even appropriate in view of his ‘special status’ as the Son of God (Byrne, 42).

Am I that special?

The three areas of testing are, in many ways, an appeal to Jesus to use his power to preserve his status as being ‘special,’ and hence, apart from the human condition. Jesus warned his disciples what would face them, and warned us, but, importantly, tempted him also: tempted to allow ‘God alone’ to be displaced by false gods; tempted to see comfort and possessions as central; tempted to use power for personal advantage and to the detriment of others.

Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness,

James Tissot, 1886-94,

Brooklyn Museum

In all this, then, we appreciate that Jesus, like us, had to make choices. He could be drawn in different directions and was not immune from the ‘wavering constancy’ of human nature. His condition was like ours, but the outcome was different. Jesus shows himself to be truly the Beloved, “God’s faithful Son, not diverted from his mission by appetite, acquisitiveness, vainglory or presumption” (Casey, 43).

Perhaps, after these thoughts, we appreciate better Jesus’ compassion for us. It was, in reality, woven into his own experiences: of being ‘on the outer;’ of choosing solidarity with humanity; of surprising moments of resistance to his Father; of being pulled in two directions. These opened doors for Jesus to that ‘inside knowing’ we call empathy. He truly ‘lives in the limitations of weakness.’

Sources:

Michael Casey, Fully Human, Fully Divine, Liguori, 2004

Brendan Byrne, The Hospitality of God, Strathfield NSW, 2006

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)