The Passover Seder – a Different Night

by Juliet Palmer

Jews celebrate the Passover (Hebrew Pesach) from the 15th to 22nd of the Hebrew month of Nissan - this year 30 March to 7 April.

The theme is of redemption. It is a holy time, where the Lord is celebrated as the great liberator of humanity. Synagogue services include special readings, psalms of praise and thanksgiving, and a service of remembrance.

Because of space constraints, this article focuses on the first night: this was the evening on which Christ celebrated the Last Supper (Matthew 26:17-30).

Understanding the Passover helps to expand our knowledge of Christ’s life and of the days before his Crucifixion.

The First Passover

The Book of Exodus records how the Lord sent Moses to Pharaoh to ask him to release the Israelites from slavery so they could serve Him. Pharaoh continued to refuse, so the Lord inflicted ten plagues upon Egypt. The tenth plague was the death of first-born children.

The Lord spared the Israelites, ‘passing over’ their homes.

Pharaoh’s resistance was broken and he chased the Israelites from Egypt.

The Passover Tradition

Originally, adult males went to the Temple in Jerusalem to offer sacrifices and bask in the divine presence. After the Second Temple’s destruction, the ritual meal, called the seder (observed on the first two nights), became the Passover focus.

Preparations begin a month before the Passover, as Deuteronomy 16:3 instructs: “Do not eat bread made with yeast [leaven], but for seven days eat unleavened bread, the bread of affliction, because you left Egypt in haste [without time for the bread to rise] – so all the days of your life you may remember the time of your departure from Egypt.”

To ensure no leaven is overlooked, breadcrumbs are deliberately hidden. The day before Passover begins, the head of the household and the children search for it. Before starting, they light a candle and pray: “Blessed art Thou, O Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, Who made us holy with His commandments, and commanded us to remove the leaven.”

Although like a game of ‘hunt the crumbs,’ which, when found, are swept up with a feather, put in a bag and burned, this ritual is important. Without finding any leaven the benediction before the first Passover meal would be in vain: “Any leaven that may still be in the house, which I have not seen or have not removed, shall be as if it does not exist and as the dust of the earth.”

Unleavened bread

The first Seder day

Communities and extended families gather to eat together and remember: “You shall tell your child on that day, saying, ‘It is because of what the Lord did for me when I came out of Egypt.’ ” (Exodus 13:8)

Children are encouraged to question the traditions: this way, their learning is cemented for future generations.

The youngest child asks four specific questions: “Why is this night important? Why can’t we eat leavened bread tonight? Why do we recline rather than sit? Why do we only eat bitter herbs?”

Seder is eaten reclining rather than sitting, to celebrate freedom.

The Seder Table

Matzah Cover

Three plates are set out.

On one, three pieces of unleavened bread, matzah, are placed in a three-pocketed cloth: one pocket for the Cohens (priests), one for the Levites, and one for everyone else. Flat and unflavoured, the matzah embodies humility. It enables those who consume it to tap into the miraculous well of divine energy we all have within our souls.

On the second plate, food is arranged: a shank bone (representing the Paschal lamb) reminds people of the lambs killed for the first Passover. An egg symbolises new life, as does a green vegetable, usually parsley or celery. Haroseth , a paste made of fruit, nuts and wine, symbolises the mortar the Israelites used to build the pyramids. Maror, bitter herbs, represent the bitterness of slavery.

The third plate has vinegar or salt water on it, symbolising the tears of slavery.

Table set for the Passover Seder

The Ritual

The seder ritual involves hand washing, blessing food (with a separate blessing for the ritually broken matzah – half is hidden for children to find after the meal and is eaten with dessert). The Passover story is told, the festive meal eaten, grace after the meal is said and the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) is recited.

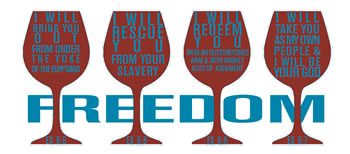

Four cups of wine are shared, with two consumed before the meal and the others afterwards. The first represents the Israelites’ salvation from hard labour, which began with the plagues. The second represents their salvation from servitude – the departure for Egypt. The third represents the Red Sea dividing and the Israelites’ escape from the pursuing Egyptians, and the fourth, the new nation at Sinai.

Thanks to Janet Salek and Ernie Rosenthal from the Wellington Jewish Community Centre for sharing their time and knowledge and Rabbi Yitzchak Mizrahi for his oversight.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)