The Origins of the Pubs in Britain

by Tricia O'Donnell

Anyone who has visited Britain would have to admit among its main attractions are the pubs! The old English pub is especially charming and towns and villages throughout the land usually have one or two – or more. Most of these gathering places have rich histories and an abundance of stories to tell, particularly those with roots firmly in the Church.

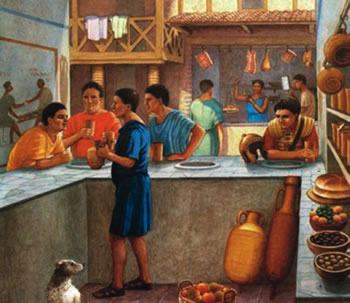

The first drinking establishments were scattered throughout Roman England. The tabernae were the Roman equivalent of today’s restaurants, as food and alcohol were served; however, when occupation ceased so did the tabernae. Ale continued to be brewed for many centuries, though not very successfully, as the art of brewing took some time to master. It appears there were ‘pubs’ of some sort, as one king ordered strict controls on the size of drinking containers – obviously even then, some drinking got out of hand!

A Roman taberna

Interestingly, as the drinks were shared, the containers were marked with pegs and no one was supposed to drink beneath the peg before passing to someone else. Occasionally they did, and the next person was ‘took down a peg or two,’ a saying we are all familiar with today!

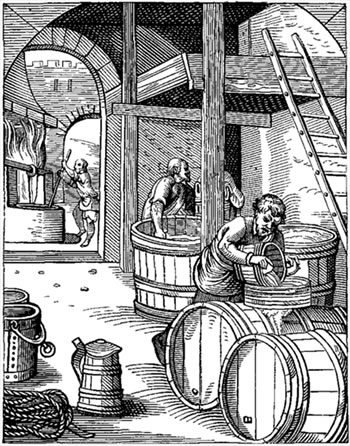

In medieval times, unsanitary water supplies made ale a staple drink with or without meals. By this time many of the monasteries and abbeys were brewing their own, and as it usually accompanied their daily meals, they became quite skilled at the craft. Hotels were few and far between, so these religious houses began accommodating travellers, which meant when they fed them, they also offered ale, and so the beginnings of the inn were born.

Beer brewing in the 16th Century

As industry increased and merchandise was transported by road, accommodation was in high demand. Further pressure came with the popularity of pilgrimages, so separate buildings began appearing alongside many monasteries and abbeys, some of which still exist today. Spiritual needs were also catered for, as often a small chapel was contained within the hostel.

Canterbury became one of the most visited pilgrimage sites after the murder of Archbishop Thomas a’ Beckett. The starting point for the journey was The Tabard inn in Southwark, London, demolished in 1874, which was made famous in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Although not adjoined to monastic buildings, it was built by an abbey near Winchester for the Abbot to use when in London, and for those travelling to Canterbury. Southwark was the home of several inns with religious connotations. The Three Widows was believed to be a corruption of the Three Nuns, as post-Reformation locals interpreted the Sisters’ head-dresses with those worn by widows at the time. The Three Brushes, which stood in the district in the mid-seventeenth century, related to the brushes used for the holy water in the Asperges, which marked the start of the Catholic Church’s high Mass.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Catherine Wheel was a popular inn sign throughout the country, including one at Southwark. It’s believed to represent the knights of St Catherine of Mount Sinai, an order originating in the eleventh century for the protection of pilgrims journeying to the Holy Sepulchre. The Catherine Wheel, a spiked wheel, was depicted on their white habits, together with a bloodied sword. Just as the knights themselves safeguarded travellers on the roads from robbers, so the inn sign told people the innkeeper was honest and kept a safe house.

A Roman taberna

Gloucester too became a much-visited holy place after the killing of King Edward II in the 15th century. He was buried in the abbey – now Gloucester Cathedral – and the abbot in charge arranged for the New Inn to be built nearby to house some of the pilgrims. An underground tunnel linked the two buildings. The inn still stands today. Another pub built for this purpose is the Star Inn in Alfriston, Sussex. It was originally called the Star of Bethlehem when the monks at nearby Battle Abbey arranged its construction for those visiting the shrine of St Richard at Chichester. An unusual feature is a wooden post inside that was a sanctuary point, where law-breakers could claim the protection of the church.

Star Inn, Alfriston, Sussex

Over time, as the demand for abbeys, churches and cathedrals grew, so too did the need to accommodate the tradesmen who worked on the sites. Skilled craftsmen travelled the country, some working on the ecclesiastical sites and others on the nearby inns that would give the workers food and shelter. Today, many pubs bear the name of their crafts such as the Mason’s Arms or the Bricklayer’s Arms.

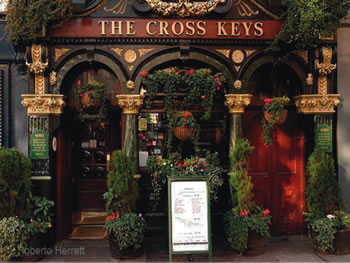

Of course, it was also quite common – and logical – that inns would be given religious names too, especially if the abbey or church was close by. The George and Pilgrims Inn in Glastonbury relates to England’s patron saint and catered for the visitors who went to the site of the Holy Thorn tree near King Arthur’s burial place. The popular Cross Keys found throughout the land relates to St Peter; the Lamb, of course, is Christ; and the Lamb and Flag is Christ and the flag of the Crusades. One of England’s oldest pubs is the Trip to Jerusalem in Nottingham which was often a meeting point for the Crusades and pilgrims to begin their journey to the Holy Land.

Photo by Roberto Herrett

The Church House or the Church Inn are other common pubs found throughout the length and breadth of England and these originated from the popular tradition of Church Ales celebrations. Feasts and holy festivals were held in almost every parish and ales were brewed for these occasions. These were sometimes called ‘scot ales,’ and often where villagers or townspeople brewed for the church, they would hold some back for themselves. Hence, it’s believed to be one source of the saying to get away with something ‘scot free’!

Church Ales went on to become widespread for all sorts of festivals, including weddings, christenings, Whitsun, Easter etc. Donations of food as well as malt for the ale were given to the church and the celebrations grew into a community affair, which along with the eating and drinking, included archery, maypole and Morris dancing. Profits received from these events were used for church maintenance or for helping the poor of the parish. The festivals were usually held outdoors in the churchyard but bad weather often forced them indoors, usually to a nearby barn or outhouse, and once they were set up for these events it was inevitable many of the buildings would become inns.

So, whether it’s the abbeys brewing their own ale, the demand for accommodation for pilgrims or much needed parish funds, many of England’s pubs owe their origins to the early Church. No doubt many patrons, in today’s secular society, would be surprised to learn that!

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)