Pā Hohepa’s Dream (1)

The June issue of the Marist Messenger contained an article by Fr Christopher Martin sm, about Fr Francis Delachienne (often known as Fr Delach).

This article, by Fr Noel Delaney sm, re-printed from the MM of April 1989, complements Fr Martin’s article. Fr Delaney died in February 2016.

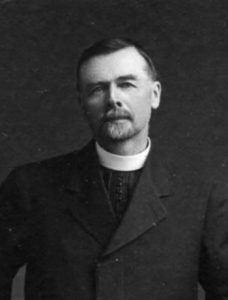

Pā Hohepa, Fr Delach

François Delach was born in Brittany, the northwestern-most part of France, in 1866. He was one of many robust, Breton missionary vocations that the great diocese of St Brieuc gave to our southern lands. On his ordination to priesthood, Father Delach offered himself for missionary work in the Society of Mary’s apostolate among the Māori people. His offer was accepted and he arrived in New Zealand on 1st January, 1891. At Pakipaki, near Hastings, he quickly became proficient in spoken Māori and developed a great empathy of heart and mind with the people.

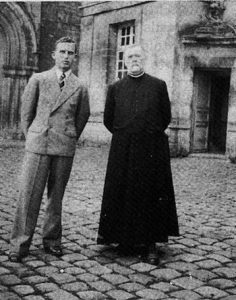

Abbaye Saint-Vincent at Senlis, France

For the next 25 years of his life, the Māori mission was his every waking thought and his midnight dream. He was quick to see that the hui or meeting was in-built in Māori life and hui were organised by him on a grand scale. Converts were multiplied among the great and the lowly; some were indeed notable. When, in 1914, there was a sudden and unexplained decision to move Father Delach from his centre of special ministry, the people were devastated. There is to be found in the General House of the Society of Mary in Rome a petition in Māori which was sent to the Superior General of the time. It is a sincere and moving appeal, as the extract which now follows in translation clearly shows:

A few years ago, Father, the Church was scorned and debased among us. We dwelt as did our fathers, scattered far outside the fold of the truth. We had faith, but it was dead faith. When Father Delach arrived among us, he dug us out of the sepulchre of death, nourished us with the Bread of Life, gave us water to drink from the living fountains. He brought back to the fold those who had been scattered and looked after everyone. The reason for Father Delach’s great success among us was that he knew how to assimilate himself to our ways and customs. With his deep knowledge of our language, he became completely Māori. That is why, when he carried out his great projects among us, he always acted in a way which was in accord with native customs; and thanks to his goodness too, the nobility of his manner of acting and the kindness of his advice, he always had our support. We can say without fear or contradiction that we have never before had a priest who was so zealous in bringing to a happy conclusion the work of the Faith among us Māori; and that we have never before seen either a bishop or priest whose word was heeded like his or had the force of law in all parts of our island and in every diocese. That is why we are so attached to Father Delach; and we are certain that if he is taken away from us the fruit of all these works will be destroyed.

Visiting Fr Delach in Senlis

In 1938, Leslie Joseph McDonald from Ōtaki, who was 21 years of age, visited Fr Delach in Senlis, France. Extracts from a letter he wrote to his grandmother, Flora McDonald, of ‘Heatherlea,’ Levin, follow:

Buckfastleigh, Devon,

13th September, 1938

Dear Grannie,

I am enclosing a copy of the notes I have written on my two visits to Father Delach at Senlis. I wrote them because I wanted to give you an accurate account of everything we spoke about, and I know it would be impossible to remember everything to tell you when next I see you. Father was so pleased to see me and very interested in all the news that I could give him about our family, and impressed on me to give his very best and sincerest regards firstly to you and then to all the others I have mentioned. He was very good to me and went to no end of trouble to show me everything of Senlis and the old College. It is a beautiful place and I think he likes it there. I hope you will find all this of interest, as I am sure you will.

Yours, Lesy.

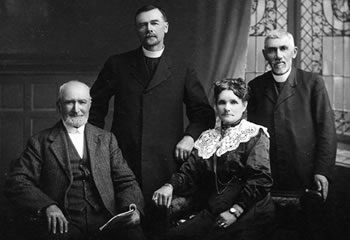

Frs Delach and Melu

with Mr & Mrs McDonald, Ōtaki

The first visit – August 5th 1938

When I first arrived in Paris I had telephoned the Institution of St Vincent at Senlis to ascertain definitely whether Father Delach was there or not. I was told that he was there.

The day I selected to visit Beaulencourt was a good opportunity to continue on and visit Senlis also, this I accordingly did and I descended from the motor bus there at a little after noon. I had lunch in a café then sought out the Institution of St Vincent. I enquired at the Concierge for Père De La Chienne. The fat old lady who indicated to me where to go asked if it was I who had telephoned some weeks previously. I told her that it was. I found my way through the cloisters of the old college building that was built in the twelfth century, up two flights of stairs to a door. I knocked and at once a voice answered ‘’Entrez” and I walked in. I thought that possibly after being so long in France Father Delach may have forgotten how to speak English so I asked him in French if he could speak English and he replied that he could a little bit, still in French. So I spoke in English and introduced myself.

He was much younger than I expected to find him, he held himself erect and appeared to carry his years well. He had a close beard, grey but not white. He wore spectacles but was not short sighted, his voice was slightly hoarse but he spoke very good English. When I told him that my name was McDonald and that I was from New Zealand he said nothing but just looked hard at me and finally asked: ‘Are you from ‘Heatherlea’?’

He seemed stunned for a moment and then shook hands and fussed around to get me a chair, seeming to take advantage of the action involved to collect his thoughts again. Then he asked me to commence at the beginning and give a full account of how I came to be there and I told him accordingly.

‘Well, well … of all the people in the world whom I may have expected to come to see me today you are the last, and yet I would rather see a McDonald than anyone else. Because if there is any family to whom I owe everything it is to the McDonalds, and there is no man whom I have held in higher regard than your grandfather.’

He went on asking one or two questions, enquiring after all the members of the family, was Ma still alive, how was Aunty Flora? He was very sorry to hear that Uncle Charlie had died and then opened his drawer and took out a letter that he had received from Flora some years ago and with it was a photo of her taken with her family. He said, ‘I always had a special regard for Flora and she wrote me a long letter three or four years ago. But I never had the courage to reply. I tried. But I could not write. There was so much I wanted to say. When I left New Zealand twenty years ago, I made up my mind to break off half of my life and bury it.’

He told me that my visit had brought a sudden rush of old memories to his head, that he would need time to sort them all out and would it he possible for me to stay the night with him. I told him that I could not stay. He then asked me if I could return to see him again before I left France. I said then I would return to see him on the following Sunday week and spend the night there with him. We then went out for a stroll around the old buildings.

Leslie McDonald with Fr Delach, Senlis, 1938

After we had looked over the buildings, Father took me back to his room and opened his drawer again and took out a four-paged letter he had received this year from Pio, all in Māori, and he thought a great deal of it. He asked me whether old Mrs Simeon was still alive and I told him she had died some time ago.

He told me that he was writing a sort of legendary Epitaph about Father Melu who he said had never received the recognition in New Zealand which he deserved. He said, ‘When the young Co-Adjutor reduced Father Melu to a stationary Parish Priest and sent me back here it nearly killed Father Melu and it killed me, so I climbed a step and pushed back the ladder behind me. I decided then that I would close that chapter of my life and never re-open it. That is why I have never written to anyone in New Zealand or kept in contact with any one of the great friends that I had made there. Now that you are here all the old faces and memories have come back to me with a rush over a gap of twenty years and I can see things as though they happened yesterday.’

He showed me some old photos that he had carefully tucked away in his drawer (which by this time I had decided must be his New Zealand museum) of Māori gatherings and two with my grandfather in them. He also showed me groups of Māoris that had been sent to him by Father Riordan. In one of these I pointed to a lady sitting in the front and asked him if he remembered her? ‘Taruru... do I remember Taruru... do I remember my right hand?’ he replied. He also had in his museum the Auckland Weeklies with all the photos of the Catholic Centenary in Auckland. He was very interested in all the celebrations and had read every bit about them.

Pilot Officer Leslie Joseph McDonald

Father Delach said that it was a great pity that the Māori missions were not allowed to continue as they were so successful and helped greatly to keep the Māoris together and help them change from their old customs to the English ways with the least harm to themselves. He said that my coming had brought to the surface so many things that he wanted to ask me that he could not possibly think of them all so quickly and wanted me to return another time. I told him that I would come back on the following Sunday week and spend the night there on my way back from Lille.

To be continued

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)