Māori and the Marists

Records of a 175 year relationship

The history of the Marists and Māori in New Zealand is woven through the history of Aotearoa/New Zealand like a harakeke leaf in a kete.

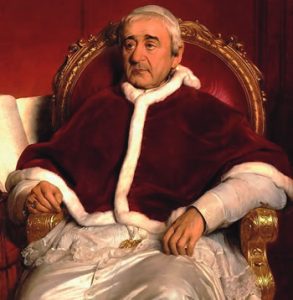

The Society of Mary (Marists) was founded by Father Jean Claude Colin in France. In 1836 Pope Gregory XVI approved the Society and commissioned it to bring Catholicism to the Western Pacific.

The Marist congregation consists of ordained priests and professed brothers. It is not to be confused with the Marist teaching brothers who are a separate group, who mostly arrived later to teach in primary and secondary schools.

The Marists were the first Catholic missionaries to arrive in New Zealand. The Anglican Church Missionaries, of course, had arrived 25 years earlier.

This article, based on the rich collection of records held in the Marist Archives in Wellington, aims to outline the 175 year relationship between the Marists and Māori.

The first group of Marists, led by Bishop Pompallier, left France in 1836. After a long voyage via Valparaiso, Tahiti, Wallis, Futuna and Sydney, they arrived in the Hokianga in January 1838 where they established a Mission, which was later moved to the Bay of Islands.

Bishop Pompallier was present at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on 6 February 1840 and played a role in the process. On the day before the signing Pompallier cautioned the assembled rangatira against assuming that the British Crown would act in the best interests of Māori. Furthermore, he was partly responsible for the fourth article of the Treaty which guaranteed religious freedom and protection of Māori custom.

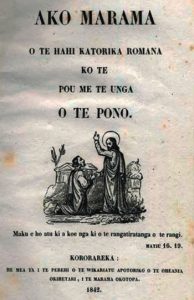

Pompallier House, which still stands in Korerareka (Russell), was the early centre of Catholicism in the far north. Its printing press played an important role in bringing literacy to Māori.

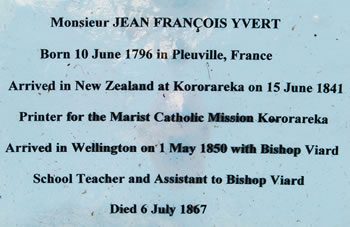

The key to this was a French Catholic layman called Jean Francois Yvert who was recruited to run the Catholic Mission printery in New Zealand.

Before leaving France Yvert purchased all the equipment and supplies required to establish and run a printery. The type he brought with him was able to be adapted to print in Māori, Latin, English and French.

Together with four priests, four brothers, two clerics and some laymen, they arrived in the Bay of Islands on 15 June 1841. Records survive of a survey of all Marist Priests and Brothers in New Zealand undertaken in 1842, and Yvert issued a strong plea to his colleagues that everyone on the Mission should have lessons in Māori and English.

Yvert established the printery at Kororareka in 1842, training two of the Marists in the art of printing. Between 1842 and 1850 they printed at least 12 publications totalling well over 30,000 volumes, and this against the backdrop of the turbulent 1840s, with war between the British and Kawiti and Hone Heke, etc.

One of their two large printing presses was removed to Whangaroa early in 1845, before Hone Heke attacked Kororareka, and was returned in 1846.

After Yvert’s departure from the Bay of Islands, the Gaveaux press found its way down to the Waikato and was used by the Kingitanga movement under King Tawhiao. From 1892 to 1933 it was used to produce the Kingitanga newspaper Te Paki o Matariki.

In 1968 it was brought back to Pompallier House courtesy of the Māori Queen, Dame Te Ātairangikaahu.

Yvert’s view on the importance of printing can be summed up in his own phrase: ‘Books are Teachers.’

There were some major differences between these early Catholic missionaries and their Protestant counterparts. Firstly, having taken vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, it meant they could not own land in their own right, relying on local rangatira to loan them land for their mission stations. By the mid 1840s some of the largest land owners in the north were the Protestant missionaries.

Secondly, they were celibate and therefore did not form relationships with Māori women – nor, in fact, women at all -- much to the puzzlement of many Māori.

The early Marists took their vow of poverty seriously.

Ensign Best recalls meeting a Marist priest on the road near Tauranga in 1842:

I never remember seeing a more miserable figure – Travel worn, unshaven and unwashed he wore the tri-cornered hat of his Order, his long coat and a kind of black  petticoat were tucked up with skirts under the waistband and a pair of old Wellington boots drawn over his trousers. From his neck hung a large crucifix and on his back was a kind of sack containing in every probability all he possessed in the world.

petticoat were tucked up with skirts under the waistband and a pair of old Wellington boots drawn over his trousers. From his neck hung a large crucifix and on his back was a kind of sack containing in every probability all he possessed in the world.

They were also French speaking, with Māori as their second language, and many who lived in New Zealand all their lives did not learn to speak English all that well.

Some aspects of their approach to Māori were also different. For example, in 1841 Bishop Pompallier wrote in his Instructions for work on the missions ;

God does not require European dress from those who want to serve Him - he wants our hearts that is all. It is better to go to heaven wearing your own country’s clothes than to go to hell in European clothes.

And another example:

Sometimes the natives insist on bringing their weapons with them to Church and even using them for exercise or recreation. They sometimes like to let off a few rounds of rifle fire. These are all things the Protestant missionaries have forbidden them to do. But this strictness shows little understanding of them – there is no evil in any of this and the Bishop does not forbid it. They are free to continue.

Many Māori were attracted to the highly ritualistic nature of the Catholic Mass, and given their relationship with their own whakapapa (lineage), many were drawn by the whakapapa of the Catholic Popes who traced their lineage back to St Peter.

The MM is grateful to Archifacts, the magazine of the Archives and Records Association of New Zealand (ARANZ), and to Ken Scadden, for permission to reprint this article.

To be continued

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)