Stories of Mercy – Antoine Garin sm

A life flowing out of compassion

To mark the Year of Mercy the Marist Messenger is presenting a series of reflections on the lives of Marists who have worked in New Zealand since 1838 and in whose lives mercy has shone. This article was first published in the SMNZ newsletter.

The Crafting of an Apostle

Many New Zealanders have heard vaguely that Antoine Garin was a remarkable and holy man. We have heard how his body, exhumed eighteen months after his burial in April 1889, was incorrupt. We know that he created highly successful schools and orphanages in Nelson and how one of his first students, Francis Redwood, went on to become the first kiwi-raised bishop. What has become clear to me is a conviction that his vision and mission were deeply rooted in the journeys of compassion that the first Marist aspirants made in the Bugey region of France in the 1820s and 30s. Even in this mountainous area far from Paris the wounds and ruptures caused by the French Revolution were much alive: priests who had taken the civil oath, laity who had seized Church property, whole families and villages that lapsed from sacramental life. The first Marists came humbly, offering forgiveness and a welcome home; they began the slow process of rebuilding parishes and schools.

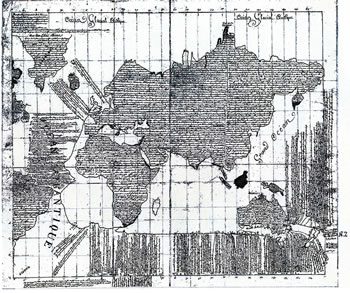

Garin was a diocesan priest of the Belley diocese. Attracted by the sense of mission to the deprived that he had seen in the Marists, he joined them in 1837 and was professed in 1840, leaving for New Zealand at the end of that year. During the six month journey he kept a diary notable for its observations of sea, bird and fish life, which also included a sketch map of the vessel’s progress using sightings obtained daily from the ship’s navigator. As he neared New Zealand he made a number of comments on how he was coming to the very antipodes of where he had grown up and how different his life would be.

A Master of Adaptation

A brief overview of Garin’s life indicates how diverse were the fields in which he laboured and how well he made the adjustments needed for each. Adaptability and versatility were to be his greatest assets, allowing him in a period of just over ten years to move from teaching in a minor seminary in France, to missionary work among the still warring tribes in the far north of New Zealand, to full-time chaplaincy to a large body of mainly Irish army veterans in Auckland, to a predominantly English settlement in Nelson. After six rewarding, if demanding, years’ work among Northern Maori, Garin was asked to transfer to Auckland. There he was to work among the Fencibles, the name given the Irish veterans settled mainly in Howick with detachments also in Otahuhu and Panmure. Nearly two thirds of his flock was Irish; he loved their strong commitment to their ancestral faith but lamented their hard drinking habits. Quickly seeing their need for structures of support, in less than three years he had put up two churches and two schools. After the announcement of the withdrawal of all Marists from Auckland in 1850, he was deeply touched by the sad farewells that were directed to him. At the little school in Panmure he could barely contain his emotion at the heart-brokenness of one of his students at the loss of their father.

Arriving in Nelson on 9 May 1850, he encountered a community dominated by English, mainly Protestant, settlers, including all the main-line churches and a good clutch of dissident religious bodies. In the whole of Waimea county, Irish numbered only 6%. In his Nelson city parish his flock was just 230 in a city of five thousand people.

Antoine was a well-educated and multi-talented man. He played a number of musical instruments; he was a gifted linguist who had gained fluency in Maori in the North. A good command of English shines out from the hundreds of letters that he wrote to the local newspaper over the 29 years he lived in Nelson. Allied to this was a very practical bent. In one of his letters home he jests how he has had to be a carpenter, wheelwright, gardener, tailor, mason, bookbinder, chemist, farmer, vinedresser and doctor. This was no empty boast. The elaborate sundial he constructed, and the gold ball and clock that he mounted on his church tower were the pride of local citizens, not just Catholics.

A Lover of the Young and Disadvantaged

When he arrived in Nelson Garin discovered that local donations had been able to provide just one small and simple building for Catholic use. Remarkably, by 1882 he had managed to build six churches scattered over his huge district. What a remarkable achievement that is, given the poverty of the majority of his flock. Much of the money was raised from contributions from goldminers in the outlying areas of Collingwood, the Lyell and Buller rivers; they were wild men, noted for turbulent lives and morality; yet they showed great respect for this priest who for many years made long treks to pastor and care for them.

It was only a short time before he had set up a school, open to students of all faiths. As his students grew in number and ability, he was able to offer subjects at secondary level, he himself teaching Latin, French, algebra and mathematics. The discipline, teaching standards and results of his school were such that many Protestant parents were happy to have their children attend, even after the district administration imposed a universal school tax in May 1856.

What is crucial in these developments is the underlying belief that drove this educational thrust. Garin was convinced that in such a strongly Protestant milieu, Catholic families and children would lose their distinctive faith and traditions unless they were provided with sound education and solid catechesis. This is also the conviction that underlay the founding of his orphanages. In 1871 he brought the Sisters of the Mission (RNDM) to Nelson. By 1880 they had grown sufficiently to take over the running of two orphanages, one for boys and the other for girls, in the convent grounds. Initially there were just six boys but by 1886 it had grown so much that a new building had to be constructed out at Stoke where the role had risen to a hundred by 1888. This served as an orphanage for the entire Wellington diocese, and even wider. At the same time he also promoted an industrial school for boys and girls, for any youth in distress.

The manner in which Garin was able to have such initiatives launched and supported in a dominantly non-Catholic area is itself an example of diplomacy and strategy. Where he could see no conflict with Church doctrine, he was willing to seek practical compromises. This contrasted with the militancy of Bishop Moran in Dunedin who, for instance, forbade Catholics to send their children to state schools. In contrast, Garin strove to promote more positive initiatives such as providing Sunday schools and catechesis for children in the Waimea area, where there was no Catholic school, making this as attractive as possible. He also built up two travelling Catholic libraries to promote the education of parents, and arranged subscriptions to Catholic newspapers such as The Freemans’ Journal from Sydney. By working with local legislators rather than constantly attacking them he was able to win concessions, such as local government support for his schools from 1867-77.

Perhaps the clearest example of such tactics was the launching of his industrial schools. Through the aid of sympathetic local dignitaries he was able to ensure the passage through parliament of an amendment to the Criminal Children’s Act of 1881. This allowed ‘industrial schools’ to accept any New Zealand child committed there by a magistrate. This allowed St Mary’s to become the first industrial school for boys and girls in the colony. He then enlisted the prominent Catholic judge Lowther Broad to run the business side of the school for him.

Despite his constant battle for Catholic causes, often expressed in letters to the editor, the esteem in which he was held by the local community was evident in a tribute to him in the Nelson Evening Mail which said that ‘he never spoke a harsh word’. For in his disputes with Protestants, he remained always courteous and reasoned. This was in striking contrast to the inflammatory rhetoric of Irish patriots on the West Coast carried in publications such as The New Zealand Celt.

A Man Marked by Pastoral Compassion

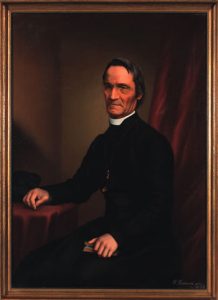

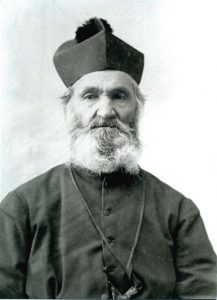

Gottfried Lindauer, Portrait of Father Antoine Garin sm, 1875. Oil on canvas. Collection of The Suter Art Gallery Nelson, NZ; Gift of The Society of Mary.

Resourceful and practical, Garin was yet simple and humble in his personal lifestyle. In his pioneer years in the North he helped build and maintain the very basic homes and churches used by the early Marists. Once in Howick he lived within the fencibles’ settlement, making his home a centre of community life. In this he won the admiration of many Anglicans whose pastors lived in the city. He was also deeply involved in the life of his schools, mingling with the students in their breaks, regaling them with stories and delighting them with the giant images cast by the magic lantern that he had procured.

In Nelson, two thirds of the parishioners lived scattered widely outside the city. So for thirteen years he made extensive journeys to serve them. He made six trips to Golden Bay 1851-57, an annual visit to Marlborough with occasional treks to the Kaikoura Coast and Hokitika. At first these journeys were made by foot until the parish had enough money to buy a horse. Such travels could cover as much as 400 miles, taking him away for months as he married, baptised and catechised wherever he found the need. On these journeys he risked his life many times in storms, mountain passes and rivers. In 1863 he was laid so low by exhaustion and rheumatism that he had to spend some months recuperating with the Redwood family in Waimea, after which he was no longer able to undertake such journeys. His openness and generosity were also much noted; when it came to his attention that anyone in Nelson was a victim of misfortune he reached out to them regardless of status or creed.

A Gift of Imagination and Creativity

Garin was a master of gatherings, using them to draw his community together, teaching and forming them at the same time. On any Church occasion he would organise ceremonies and blessings. In between he would invite local people to ‘tea parties’ with parades and flags, and demonstrations of his students’ achievements. This was his mode of operation in Waimea where there were no Catholic schools. He would gather the students for catechism classes, dishing out ‘bonus points’ for good work. These would accumulate and be redeemed for Catholic books and cards at the end of the year prize-giving.

A rich European tradition of music and ritual also marked Garin’s parish. He imported vestments, ornaments and pictures. His church bell rang out the Angelus daily; every Sunday was marked by a sung High Mass. He used every opportunity to invite visits by bishops. A superb instance of this occurred in Bishop Redwood’s visit to his home parish. Though there had been a brief foray to open a church, the visit of mid-January 1875 was more in the nature of a civic reception. When the bishop’s ship entered the harbour it was greeted by flags aflutter, a salvo of cannons and the music of an artillery band. After various addresses, a procession headed for the church, led by the band and followed up by a host of banners, the orphans, various sodalities, the sisters and the cross-bearer, after which came the bishop and clergy with the laity bringing up the rear.

At the heart of this pomp and busy life, one value reigned supreme, nevertheless. None of this was designed to advance Garin’s self-image or status. Everything he did was to promote the Church’s mission as teacher, healer and refuge to those in need. So successful was he in these efforts that in 1880, more than half of his congregation were converts. Had this life been lived out in France or Italy I am sure that Antoine Garin would have been canonised many years ago.

Tagged as: Antoine Garin sm

Comments are closed.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)