Mary for Today: Mary in Culture (3)

Introduction

To find out what any text in Scripture means, it is obvious that the social system behind the text is of prime importance. The world of the first century Eastern Mediterranean had its own social system and its highest values were kinship and concern for honour and shame within a gender-based division of labour. The infancy gospel accounts provide the roots of our thinking about Mary, but these focus on Jesus, not Mary. It is a given that all the Gospels are written from the far side of the lens of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Jesus, the opposite direction to the way we read them as birth to death and resurrection. In antiquity, the description and assessment of the birth and childhood of notable persons inevitably derived from the adult status and roles held by that person.

Implications

Jesus as the Messiah, raised from the dead by the God of Israel, would obviously have a birth and childhood as the Gospels describe. The idea that personality can change was completely alien to Greek and Latin biography; a life account of the time was of persons consistent throughout their times. Titles such as ‘great,’ ‘Son of the Most High,’ ‘holy,’ ‘Son of God’ (Luke 1:15) and ‘save his people,’ ‘God with us’ (Matthew 1:21, 23) attain their full meaning as titles of the Risen Christ and are read back on the child to be born, ‘pre-flections,’ we might call them. Certain characteristics were had from the very moment of birth and remained throughout life.

After the moment in which Mary said her yes to God’s angel to be the mother of Jesus, aware that the son she conceives was special, she takes a trip alone from Nazareth to a city of Judah. The fetus is capable of warding off evil and protecting the mother, and even being recognised by another fetus, Zechariah’s and Elizabeth’s son to be. Another typical feature is that God knows the prophets even before they are born, consecrates them and calls them from their mother’s wombs. Elizabeth proclaims Mary blessed because of her reproductive role: ‘blessed is the fruit of your womb.’ Typically throughout the Bible when God communicates with women it is about their reproductive functions and subsequent gender-based roles. God as the author of life is deeply involved in that life; when a child is born, ‘God remembered/made her conceive…’

In the Gospels we find Jesus challenging his mother and even distancing himself from her and her Mediterranean claims on him: ‘Here are my mother and brothers!’ (Mark 3:31-35); ‘Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and keep it’ (Luke 11:28). Also the Synoptic tradition knows nothing about Mary at the foot of the cross, while John mentions the presence of the unnamed beloved disciple and the mother of Jesus there (John 19:25-27). Who they are is not clear, because the Gospel of John seems to know nothing of Jesus’ Davidic pedigree or birthplace (John 7:40-44). There is no indication that the author knew the name of Jesus’ mother even though he places her at Cana and Calvary. Is it done deliberately to emphasise her symbolic role at the expense of her real role? Without the Synoptic tradition, chances are ‘Mary of Nazareth’ would not be remembered at all.

Regardless of the extent of our ignorance of the actual figure of Mary of Nazareth, the fact that Jesus had a mother would alone have been sufficient for the Mediterranean world to generate an attitude towards that relatively unknown personage, the mother of the Lord.

Mediterranean Kinship Units

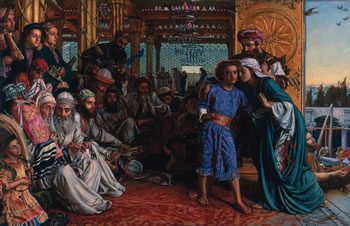

For Mediterranean people the one great goal in life is the maintenance and strengthening of the kinship group and its honour. Actions that strengthen in-group cohesion are honourable, actions that weaken such cohesion are not. The underlying Mediterranean value is kinship or family loyalty. The social value of group attachment is at stake. Jesus attempts to loosen family bonds when they proved contrary to the spirit of a renewed Israel (Mat 10:34-36; Luke 12:51-53; Mark 10:29-30). The mother-son bond is a distinctive by-product of Mediterranean child-rearing practice. One can sense the tension in the Lukan account of the finding of the child in the Temple (2:41-52) as well as in the one moment when Mary appears with the family during Jesus’ public ministry. The passages in Mark 3:23-35 are named ‘A House Divided’ and ‘Jesus’ True Relatives’ – and that says a lot!

If the infancy accounts and even the gospel story itself indicate anything, Jesus’ birth was surrounded with many problems and questions, indecision, confusion and dysfunctions, yet duly miraculous. Conditions in the story and the culture point to parents and families that tend to promote confusion – for Joseph and his own family; Mary and her family. Mediterraneans are taught to keep all family secrets within the family. Honour must be protected at all costs. But persons have their feelings, especially of hurt, but are quick to learn to repress and deny those feelings. Mary paid a heavy price in her culture for her ‘yes’ to God.

Reference: Bruce Malina, 'Mother and Son'. Biblical Theology Bulletin. Vol.20.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)