Tracking the Origin of the Pompallier Madonna

According to the Marist Messenger of September 2013: “The Pompallier Madonna is a painting of the Blessed Virgin brought to Rome from Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul) by the nuns of the Immaculate Conception in the Campus Martius in the year 750.”

That sentence conveys the impression that the painting Bishop Pompallier was given by Pope Pius IX in 1847 was an icon brought from Constantinople a thousand years before. We cannot check with the actual painting because it went missing from St Patrick’s College, Wellington in 1978, however the reproductions do not look like an ancient icon.

In the 1960s there was a lithograph made of the Pompallier Madonna, which bore the caption:

IMAGO B.V. ROMAM A BYZANTIO / TRANSLATA A R.R. MONIALIBUS IM.CON.IS / IN CAMPO MARTIO AD DCCL

That translates as: “Image of the Blessed Virgin transferred from Byzantium to Rome by the Reverend Sisters of the Immaculate Conception in Campo Marzio 750 AD.”

The caption is written below the lithographed image, but no-one reading it would think that it is the lithograph itself is that is being referred to. The caption relates, at least to the original (the Pompallier Madonna) of which the lithograph is a reproduction. I am going to suggest that a similar caption may have been associated with the Pompallier Madonna and it too is a copy of the image to which the caption refers.

Now, there is a district of Rome called Campo Marzio (The Field of Mars) which was a military training ground in the time of Ancient Rome. In the central piazza of that district there is a convent and church dedicated to Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception (in Italian the church is called ‘Santa Maria della Concezione in Campo Marzio’). The ‘in Campo Marzio’ gets added to distinguish it from the more famous Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, (The Capuchin church of Our Lady of the Conception) in Via Veneto in Rome. That church is famous for its ‘memento mori’ displays of skulls and bones in the crypt, though to add to our confusion it is also the place where Pompallier was ordained as a bishop.

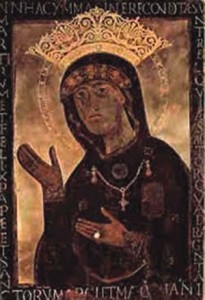

However to come back to the church in Campo Marzio, above the high altar in that church there is an image of the Blessed Virgin of the style called Madonna Avvocata (Our Lady Interceding).[See Figure 2] The ‘interceding’ or ‘advocating’ is shown by her hand gesture, she is asking something of another figure. A person prays before the image, confident that Our Lady is interceding with her son on their behalf.

Even from the photo it is evident that this is the original of which the Pompallier Madonna is a copy. The odd posture of the hands, the drape of the garment, the border around the robe, the wrist bands, the decorated band above the brow, are present in both paintings. The decisive factor which makes the connection certain is the crown. In the Pompallier Madonna this is painted in an oddly flat fashion and perched on Mary’s head. In the SM della Concezione image the crown is metal and is an addition to the icon (therefore is flat and perched). It is on record as having been added as an act of devotion and respect in 1655 AD.

It follows that the Pompallier Madonna is a painted copy of the Santa Maria della Concezione icon made somewhere between 1655 and 1847. Given the style, it was probably made towards the end of that period, in the 1800s. At some stage it was given to the Pope and, in 1847 it was given by the Pope to Bishop Pompallier.

Now the tradition of the Church in Campo Marzio has it that the icon above the altar was brought from Constantinople at the time of the Iconoclast crisis (730-787 AD) when religious pictures were outlawed and destroyed in the Eastern Roman empire. That would account for the “750 AD” on the lithograph. The date does not refer to the Pompallier Madonna, but to the icon of which it is a copy.

However even this has been disproved by art historians. There are several ancient Madonna Avvocata icons in churches in Rome, all claiming to be the original miracle-working icon brought from Istanbul. Sometimes the claim is even stronger, that the icon is either “not made by human hands” or “was painted by the Evangelist Luke”

The most famous of these icons is the one in Santa Maria in Aracoeli. This is a huge church built in the very heart of Rome on the Capitoline Hill.

Modern research has shown these icons to be about one thousand years old, which is very ancient but well short of the iconoclast period. Looking at the images (Figures 2 – 6) it is obvious that there is some kind of connection between them all. They have too many features in common: the hand position, the big eyes, the decorative trim above the narrow forehead, the embroidered cuffs, the long neck, the oddly sad face framed by an asymmetrical head-covering with a large circular halo behind.

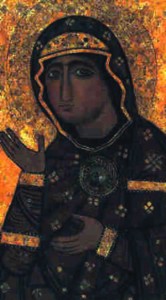

The answer is to be found in the convent chapel of Santa Maria del Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary) on Monte Mario in Rome, where a community of Dominican Sisters celebrate the liturgy before an icon covered in a bejewelled metal cover and protected by a heavy grating. (Figure 7)

As well as being “crowned” as an act of devotion and respect, icons are often “clothed” in an oklad, the thin metal covering with holes for the face and hands (also called a ‘riza’ or a ‘revetment’). When the oklad over this icon was removed a fascinating painting was revealed. This is a true Byzantine icon, with gold background, painted on linden wood (71.5cm x 42.5 cm) the colour on Mary’s garment has almost completely disappeared over the ages. The deterioration of the colouring follows the lines of what must have been an okclad that covered it for a long time. This oklad revealed the face and a part of the hood of Mary’s robe, decorated with a gold cross, which gave the impression of a decorative trim. The icons earlier in this article are all based, directly or indirectly, on this holy image. The copyists did not see all the painted image, they were looking at it with a metal covering over it.

The icon has been in its present location since 1931, before that, it and the community of Dominican Sisters had been in a convent called San Sisto (hence the current name of the icon). They had shifted there in 1220 AD from the monastery of Santa Maria in Tempuli on the slope of the Celian Hill in Rome. That is as far as historical records go, though there is a legend that in the 700s, an exile from Byzantium named Tempulus gave the icon to the Greek monastery of Saint Agatha which then changed its name to Santa Maria in Tempuli.

According to the scholars, this icon does date from before the iconoclast controversy, the style is subtly different from later icons, more three-dimensional. The painting technique, encaustic, is very early. The artist heated beeswax and mixed his pigments in with it, then applied it to the wooden surface. When he had the painting looking right he applied heat to the whole thing causing the mixture of wax and pigment to penetrate into the wood and fuse into a smooth and durable whole.

This is one of the oldest surviving icons of the Blessed Virgin Mary, one of a handful which survived the period of the destruction of icons. Some scholars date it the 500s. It would have originally been part of an iconostasis alongside an image of Jesus to whom Mary is interceding. It has been loved, honoured and prayed before for many centuries.

Thus when we display a copy of the Pompallier Madonna, we are putting ourselves in a long tradition of honouring the Blessed Virgin and asking her to be our advocate. That image is part of an artistic tradition, being a copy of the much-loved Maria Avvocata of Santa Maria della Concezione, which is, in turn, based on the yet more ancient Madonna of San Sisto.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)