God’s Traveller – Blessed Pope John XXIII (1881 – 1963)

Today, Pope John XXIII is mostly remembered as the instigator of Vatican II. His sometimes controversial “new Pentecost” tells us little of the man behind the reforms he brought about. Yet there’s so much more to tell of this extraordinary man.

He was born Angelo Guiseppe Roncalli on a cold, wet November day in 1881 in the small village of Sotto il Monte in Bergamo, Northern Italy. His parents were poor tenant farmers and when their first son was born – he was the fourth child of what would be thirteen – he was baptized on the same day. The patriarch of the family Uncle Zaverio, then took the baby before the statue of Our Blessed Lady and dedicated him to her.

Despite growing up with limited means in such a large household, which included his father’s cousin, his wife and ten children, Angelo’s childhood was a happy one. In his later writings, he vividly recalled visiting Our Lady’s shrine, near the village, with his mother and siblings. They were forced to stand outside the crowded little chapel and his mother picked him up so he could see through the window. His eyes rested on a picture of Mary over the altar; it was a memory that would remain with him all his life.

From an early age Angelo knew he wanted to be a priest. He was almost twelve when he entered the seminary at Bergamo, and two years later began the diary in which he would record his spiritual progress, throughout his life. After his death it was published as Giornale dell’Anima “Journal of a Soul”. His early writings tell of a boy, desperate to love God, worried about distractions in prayer, trying to overcome pride and “to become a priest, in the service of simple souls”. A natural extrovert, Angelo struggled daily against being a ‘chatterbox’, trying to avoid gossip and being too ready to voice an opinion. He once promised himself he wouldn’t be so merry, but some months later, realising he was fighting a losing battle, reminded himself that it was “better to be merry than to be melancholy” and to “be glad in the Lord”!

Several years later at the age of 22, acceptance of himself came. St Aloysius had long been Angelo’s role model and the realisation that he could not live up to the Saint’s holiness, was revealed in his diary: “I am not St Aloysius, nor must I seek holiness in his particular way, but according to the requirements of my own nature, my own character, and the different conditions in my life.”

In the intervening years, Angelo, despite his own misgivings did well at the seminary and at the age of 19, moved to Rome to complete his studies. Barely a year later he was conscripted into the army for a year’s service. His ‘Babylonian Captivity’ as he called it was at the Military Hospital in Bergamo, and though becoming aware first hand of the evils of the world he also gained precious knowledge of humanity. He spoke warmly of the kindness and reverence he received there, was promoted to corporal and shortly before leaving, became a sergeant.

Two years after returning to the seminary, on the 10th of August 1904, Angelo was ordained priest. The following day he celebrated his first Mass at St Peter’s in Rome, a joyous occasion for him: “I said to the Lord over the tomb of St Peter, and in his words, ‘Lord you know everything; you know that I love you’” – words repeated often throughout the troubled days of his diary. After his ordination however, a new maturity set in and his spiritual shortcomings were no longer recorded.

A few days later on the feast of the Assumption, the 15th of August, Father Roncalli was home and celebrating Mass at his small village church of St John the Baptist. “I count that day among the happiest of my life, for me, for my relations and benefactors, for everyone…” He added that an elderly man of the village advised him to “work hard and become Pope!”

Work hard was what Angelo planned to do, beginning with a course in Canon Law. He’d just began his studies when the new Bishop of Bergamo, Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi chose him to be his secretary. At a time when Catholics were discouraged from being involved in politics, the bishop felt strongly about social reform. Under Pope Leo XIII he’d been responsible for running the Opera dei Congressi a conglomeration of Catholic social action groups, a position curtailed when Pope Pius X was elected and the organisation was dissolved. Though no longer active in the work he loved, the bishop recognised in the young priest, someone whose beliefs and philosphy matched his own.

Angelo remained in this post for the next ten years until the death of Radini-Tedeschi, who died two days after Pius X in August 1914. He planned to return to his studies, but once again, was taken in another direction. Italy entered the First World War in 1915 and Father Roncalli was among the many priests called up for the medical services.

He began there as an orderly before eventually becoming chaplain. In later years as Patriarch of Venice he wrote about how much he had learnt about the human heart at that time, “how much experience I gained, how much grace I received to be able to dedicate myself to the performance of my duties as military chaplain.”

After the war, Angelo ran a hostel in Bergamo for lay and university students. He relished the work among the young people, often using his own funds to furnish the place. It wasn’t all smooth sailing - he received criticism that the rules weren’t strict enough and there was a lack of discipline, but for the most part, he paid no heed. “I will recognise no other school than that of the divine Heart of Jesus”, he wrote at the time, “ ‘Learn from me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart’. I will love my students as a mother her sons, but always in the Lord.”

Just over two years later he was recalled to Rome to take over the running of an organisation which handled fund raising for missions. Although based in Italy, Angelo was required to travel throughout Europe, “God’s traveller” as Pope Benedict XV called him. In May 1921, he became Monsignor Roncalli; he was ascending the ecclesiastical ladder and leaving the simple parish priest of his aspirations behind.

Three years later, under Pope Pius XI came another change of direction when he was appointed Apostolic Visitor to Bulgaria, a difficult assignment as Bulgaria was experiencing turbulent times both politically and spiritually. Revolution was in the air; there had been assassinations of government members as well as an attempt on the life of the king. Catholics were in the minority as most Christians were Orthodox – even the Catholics were split as some recognised the Pope as head of the Church while others didn’t. This deeply divided country needed a man of authority so Pius sent a newly ordained Archbishop Roncalli.

Obedience to his superiors overrode his reservations, so in April 1925, Angelo left for Bulgaria. The next ten years brought some highs and many lows: “My ministery has brought me many trials,” he wrote in his diary. “But, and this is strange, they are not caused by the Bulgarians for whom I work but by the central organisation of ecclesiastical administration…this…hurts me deeply…‘Set a guard over my mouth, O Lord’.”

Archbishop Roncalli threw himself wholeheartedly into his work, despite feeling a constant lack of ministering, “I never hear confession”, he wrote. He learnt the language, travelled, often to remote villages by horse and cart and became a popular figure among the different faiths. Barriers were there to be broken: “Whenever I see a wall between Christians, I try to remove a brick.” No one could have guessed how unhappy he was, but his diary spoke of his “acute and intimate suffering” that he would “bear willingly, even joyfully for the love of Jesus in order to resemble him as closely as I can.”

The war years brought fresh challenges. His friendliness and easy manner enabled him to stay on good terms with all he came into contact with, including the German Ambassador. He persuaded the Italian and German embassies to supply food to the occupied Greeks and worked tirelessly to help as many Jews to safety as possible by arranging visas for Palestine.

Then, in December 1944, came another move and another promotion. This time, a very surprised Archbishop Roncalli was sent to Paris as Papal Nuncio, an impressive position which brought a philosophical response: “When the horses break down they trot out an ass!” But while he’d sometimes suspected over the years that he had been forgotten about by his superiors, he was finally being recognised for all he had achieved to that point. Much diplomacy was needed in France to deal with the many changes happening with the Church and the state – the Vatican knew just the man for such a sensitive situation.

On his return from Paris the Pope had other ideas for him and in early 1953, Cardinal Roncalli arrived in Venice to become its Patriarch.

At last, his dream as a young man was to be fulfilled: he would have his pastoral duties. “For the few years that remain for me to live, I want to be a real pastor, in the full sense of the word,” he wrote. Venice was not far from Bergamo so Angelo felt he was on home ground, and from the outset the Venetians took him to their hearts. In his first speech to them, he spoke of his “inclination to love men….it prevents me from doing evil to anybody. It encourages me to do good to all.”

The years had done nothing to diminish his passion for unity. “My heart is big enough to wish to encompass all mankind,” he said and throughout his five and a half years in Venice, he attempted to do this. He chatted to children in schools, visited the sick as well as the poorer areas of his diocese. After entertaining other cardinals and priests the Patriarch would thank the staff in the kitchen for the meal and the work carried out. Brick by brick he was dismantling the walls between his office and the people of Venice and they loved him for it.

Cardinal Roncalli fully expected to end his days in the city he loved but in 1958, his path took a final and dramatic turn when Pope Pius XII died and Rome beckoned for the funeral and the Conclave. When he was elected Pope and asked if he accepted the role, he did so adding, “I tremble and fear seizes me….” He chose the name John as it was his father’s name, his little village church and two saints dear to him, John the Evangalist and John the Baptist.

As Pope John the XXIII, he picked up where he’d left off in Venice. He met the people on the streets of Rome, in schools, hospitals, churches – anywhere which enabled him to reach out to humanity. “These visits outside the Vatican are a great joy to me,” he once said. “The Pope is a recluse in his great palace; all the world comes to see him, but..he lives in two or three rooms at most, all enclosed. Let the Pope come out a little, to inspire you with Christian ideals and to help us all in our sacrifices.”

After celebrating Mass on Christmas Day in 1958 he visited Rome’s two children’s hospitals and the following day caused a stir by going to the Regina Coeli prison.

“You could not come to me, so I came to you,” he told the prisoners.

He caused a further sensation when he spoke of a relative who served time for poaching – for a Pope to admit to such a thing did not go down well with the Vatican Press! When a prisoner asked if there could be forgiveness for him, a murderer, the Pope embraced him.

Pope John was as controversial inside the Vatican as outside. Tradesmen and workers would down tools when he appeared as he was always ready for a chat; the gardeners who, under Pius XII had to discreetly disappear if the Pope wished to walk in the garden, were told that was no longer necessary. In talking to them he learnt of their poor pay and saw to it that they all received increases. He refused to eat alone so when he wasn’t entertaining other clergy, he could often be found at the table of the Vatican staff. He could find nowhere in Scripture, he said, that one should eat alone, even “Jesus loved to eat in company.” A visitor finding himself hopelessly lost in the Vatican one day turned to find the Pope with his finger to his lips, whispering “Ssh, I’m lost too!”

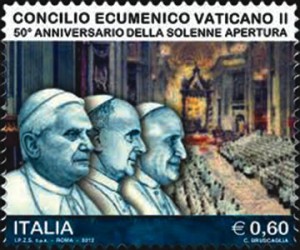

However when it came to Church affairs, Pope John could be deadly serious – as was proved by his calling of the Second Vatican Council, the “new Pentecost”, that of the Holy Spirit breathing new life into the Church. Poverty in the Third World, peace in an increasingly nuclear threatened world, greater tolerance and understanding between faiths and a revision of the liturgy in Catholicism were all issues the Pope was passionately concerned about and that Vatican II was to deal with. When the Council was finalised in 1965, the transformation of the Church began.

Sadly, Pope John the XXIII would not live to see the changes he sought. Towards the end of 1962 he was diagnosed with stomach cancer and on the 3rd of June 1963, the day after the Feast of Pentecost, he passed away. Throughout the last hours of his life he was heard to keep repeating, “That they may be one.” Even to the end, world unity was on his mind. “Good” Pope John became Blessed Pope John XXIII on the 3rd of September 2000 by Pope John Paul II.

As the 50th anniversary of his death nears, on the 3rd of June 2013, it’s timely to remember this special man whose short occupation of Peter’s Chair, had such a huge impact on our Faith and on the world.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)