The Gospel of Matthew (Part 6)

Chapters 21-22:

Jesus the King comes to Jerusalem

In Matthew’s account, Jesus enters Jerusalem and goes to the Temple on his first day there. Matthew closely follows his Markan source, but adds materials from his own traditions.

Matthew points to Zechariah 9:9 to explain the arrival of Jesus: “Look, your king is coming to you, humble…” In order to stress Jesus’ humility, Matthew omits from the Hebrew text of Zechariah the words “triumphant and victorious,” thereby emphasizing how Jesus is King. He is not a conqueror, but rather the Suffering Servant of the Lord. The crowd greets Jesus with the standard greeting to pilgrims from Psalm 118:26: “Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!” By Jesus’ day, the phrase “the one who comes” had also acquired messianic overtones.

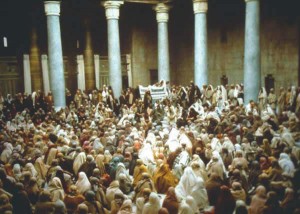

Jesus’ disruption of the commercial activity in the Court of the Gentiles in the Temple would certainly be unpopular because Jerusalem’s economy was largely dependent on the money spent by pilgrims at festival times. Jesus’ symbolic action foreshadows the eventual destruction of the Temple by the Romans. But in the storyline, Jesus is visiting Jerusalem for the first time, and he, as King and Lord, takes possession of the city and its Temple.

Jesus’ authority is immediately challenged by the religious leaders. Matthew combines some material from Mark with some of his own material to produce three parables (the Two Sons, the Lord’s Vineyard, the Great Supper) and three controversy stories (the question of taxes to the emperor, the Sadducees’ denial of the resurrection of the body, the Great Commandment). Jesus targets his opponents in the parables and bests them in their attempts to trip him up.

Chapter 23:

The Scribes and Pharisees (and us Christians)

Jesus acknowledged that the teachers of the Law were the successors of Moses. He told his disciples to follow their instruction but not to imitate their lives. “They do all their deeds to be seen by others…They love to have the place of honour at banquets and the best seats in the synagogues…” (Surely there were some scribes and Pharisees who were sincere men who followed the Law faithfully and who did not flaunt their positions. This chapter of Matthew has helped to create a caricature of all Pharisees.) One cannot help hearing between the lines of Jesus’ denunciations the friction between Matthew’s community and the religious leaders (rabbis) of the synagogues in the 80’s when this Gospel was written. This chapter has a polemic tone that is best understood in the context of the struggle between Jews who believed in Jesus and those who did not accept him concerning the future of Judaism.

Jesus often used hyperbole. For example, Matthew 5:29: “If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell.” Clearly Jesus did not intend this to be taken literally. Fundamentalists charge that Catholics violate the teaching of Jesus in verse 9 (“And call no one your father on earth…”) by referring to their priests as “Father” and to the pope as “Holy Father.”

Jesus used hyperbole in that verse. If he meant it literally, how would we refer to our human fathers? The New Testament letters are filled with examples of spiritual father-son and father-child relationships. Consider Paul’s calling Timothy and Titus his sons (1 Corinthians 4:17; 1 Timothy 1:2; 2 Timothy 1:2; Philippians 2:22; Titus 1:4). Paul tells the Corinthian Christians (1 Corinthians 4:14-15): “For though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I became your father in Christ Jesus through the gospel.”

Brendan Byrne, S.J. (Lifting the Burden: Reading Matthew’s Gospel in the Church Today) reminds us that Matthew is also addressing us Christians, warning us of hypocrisy: “Underlying the polemic of Matthew 23 and emerging expressly in vv. 8-12 is a warning: ‘This is not how it must be among you!’ The words of Jesus are an admonition to the Christian community and as such remain addressed by the living Lord to the Church. Though the chapter must be read with great sensitivity in regard to Judaism, we cannot simply say, ‘Oh, it’s all about back there. It doesn’t apply to us!’”

Chapters 24-25:

Jesus’ final discourse

In the first three verses of chapter 24, Jesus leaves the Temple and goes to the Mount of Olives. There are echoes here of Ezekiel 11:22-24. In that passage the divine glory departs from the Temple to “the mountain east of the city,” that is the Mount of Olives, where Jesus gives his final discourse. In this final address Jesus uses standard apocalyptic terminology to speak of both the fall of Jerusalem and the Temple and also the coming of the Son of Man at the end of time.

Today we look back to the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus, but his Second Coming is not our daily focus. In the first century, the opposite was true, the return of Christ being constantly expected. By the time Matthew wrote his gospel, the delay in Jesus’ return was raising questions. Daniel J. Harrington, S.J. (The Gospel of Matthew, volume 1 of the Sacra Pagina Series) suggests the following dialogue.

Matthew’s Jewish opponents: “When is he [the Son of Man] going to come? You say in ‘this generation.’ Well, where is he? In fact we are skeptical about the whole business of apocalyptic scenarios and timetables, to say nothing about the Son of Man.” Matthew and his community might respond that no one knows the precise time of the Son of Man’s coming. But their answer would be, “Watch, therefore, because you do not know in what day your Lord is coming.” Uncertainty about the time of the Second Coming is blended with the need for constant watchfulness. This has been the Church’s position throughout the centuries.

The parables of the thief and of the two servants emphasize the need for watchfulness, making it a criterion for the judgment. The final parable of the sheep and goats makes the corporal works of mercy the criterion. Of this we can be sure: Christ will come again.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)