Caroline Chisholm: The Emigrant’s Friend

When the Emerald Isle arrived in Sydney in September 1838, among its passengers was a family who would change the face of immigration in the colony. Archibald and Caroline Chisholm, together with their two sons, had made the long seven month journey from Madras, where Archibald was Captain in the East India Company’s army.

Caroline had married Archibald eight years earlier only after he had agreed that she could continue her charitable work. (Though in years to come, he would work as hard as his wife to improve life for new immigrants). She grew up within a ‘well to do’ farming family and though her philanthropic father died while she was young, her mother encouraged her to help the less fortunate in their small English village.

Although they married in the Church of England, Caroline converted to her husband’s Faith of Roman Catholicism around that time. It wasn’t a decision she would have taken lightly in an age of antagonism and opposition to the Roman Church, nor would she have done it had she not believed emphatically it was the right thing to do. At age 22 it was an early sign of her strength of character.

Two years after their marriage came the posting to Madras. Within a short time of arriving Caroline was busy planning a school for the soldiers’ daughters at the barracks. After much persuasion, The Female School of Industry for the Daughters of European Soldiers was born and while government subsidies took care of the financial side of things, Caroline ran the school together with a schoolmistress and matron. Along with basic academics, housekeeping and cooking skills

were taught.

Six years and two sons later the Chisholms set sail for Australia; sick leave was necessary for Archibald and they opted for the Antipodes rather than return to England. They left on the 23rd of March 1838, spending time in Mauritius, Adelaide and Hobart before arriving in Sydney in September 1838. By the end of 1939, a third son was added to the family. In early 1840 when Archibald was recalled to active service overseas, Caroline decided to remain in the colony with the boys.

New South Wales by this time, was heading into depression and one of the most obvious indications of this were the swarms of immigrants roaming the streets looking for work. Caroline was particularly worried about the girls, many of whom turned to prostitution as a means of survival. She began meeting every ship that docked, talking to the girls, advising them, sometimes giving them shelter in her own home and finding them positions within families. But it wasn’t enough, the scale of the problem was too big; the answer she decided was a ‘home’ where the girls could stay, while seeking employment or other accommodation.

Many months of soul-searching and indecision followed. Caroline had her own family to consider, nor was she comfortable committing herself to such a huge project, being relatively new to the colony herself. Then there was her Catholicism – many were deeply suspicious of all things Catholic and she knew her motives would be scrutinised. Finally, she could ignore the situation no longer. She wrote to the Governor’s wife, then the Governor himself – writing several times asking for help, but without success. She approached the Sydney Herald, who insisted she get the Governor’s approval before they pleaded her cause.

Sheer persistence on Caroline’s part resulted in a meeting with Governor Gipps who described his amazement at meeting with a “handsome, stately young woman,” instead of “an old lady in white cap and spectacles.” However, he wasn’t persuaded and Caroline was forced to explore other avenues, though not before she had immersed herself in prayer. At Mass on Easter Sunday 1841 she vowed to “know neither country nor creed, but to serve all justly and impartially…to surrender all comfort…and wholly devote myself to the work I had in hand.”

Caroline made herself known to the influential women of Sydney, constantly laying the groundwork for the ‘home’ she intended would come about. Eventually, towards the end of the year, with publicity concerning the immigrant girls and their plight gathering momentum, the Governor agreed to let Caroline have part of the old wooden Immigration Barracks. The Female Immigrants’ Home was finally established.

With the boys safely cared for by a nanny at their rented home out of Sydney, Caroline began organising the accommodation for the women, around ninety four were housed there at one time. She also operated Sydney’s only free registry for finding employment, both in town and in the country where labour was always needed. Circulars were sent to community leaders, magistrates and clergymen asking a variety of questions concerning wages, types of work available and accommodation provided. Families were also included in the survey: what work was available for married couples? What about those with young children – would the youngsters be provided for/protected? Could employment be found for older children? She was now concerned about all immigrants and had families housed in tents outside the Barracks.

When Caroline learned that bullock drays delivering wool and other merchandise to the city were returning to the country empty, she struck a deal with the drivers to take sixteen passengers, eight people per dray. She accompanied them on horseback. Employment was found for at least one person at each farm en route. So began a successful system of dispersion. With the backing of the Sydney Herald who made regular fundraising appeals on her behalf, she was able to organise several drays or carts, often transporting about a 100 immigrants.

Depots were eventually established along the way, providing some accommodation while enabling employers seeking staff to apply direct to the agent in charge. Incredibly, within a year of starting her immigration assistance Caroline founded depots at Liverpool, Campbell Town, Parramatta, Goulbourn, and Yass travelling regularly by dray. Other branches also opened that year were at Port MacQuarie, Moreton Bay, Wollongong and Maitland, only accessible by boat.

In delegating the work out to these ‘resting places’ as they were called, Caroline, with her usual efficiency, drew up service contracts in triplicate so that she, the employer and the immigrant were quite clear about the terms of employment. Once the branches were running smoothly, Caroline then opened a school at the Barracks for the immigrant children. Religious teaching was supplied by a Catholic and an Anglican priest, as well as a Presbyterian school mistress.

Caroline’s attention then turned to conditions aboard the immigrant ships. Young girls were placed with families, supposedly for their protection, but often both parties only met after boarding, which meant little or no vetting of the family having taken place – or the crew for that matter. She helped a woman called Margaret Bolton whose health was permanently damaged by horrific abuse she’d suffered at the hands of a ship’s captain and surgeon. The two men were subsequently imprisoned for six months and fined fifty pounds.

By the end of 1842, a full year after Caroline began her campaign, much had been achieved. She had helped around 2,000 immigrants find homes and employment, over 1,300 of whom were women who had avoided a life of prostitution. Several branch homes had been opened, enabling her to close the girls’ home as it was no longer necessary for them to stay in Sydney and public funding now meant she had no debts.

Over the next few years Caroline continued her work, transporting people out to the country as well as setting immigrants up with their own parcels of land, which came about when a wealthy landowner donated 4,000 acres in the Wollongong district for her cause. In 1845 Archibald retired and returned to Australia, where his wife was working on ways to better portray life in the colony to the British. Inaccurate reporting had led to many disillusioned immigrants, and she felt that if the settlers told their own stories, only the industrious and those truly passionate for a new way of life, would make the journey to the other side of the world.

The Settler Survey

With Archibald’s full time help, the couple travelled throughout the countryside- at their own expense - dispensing forms requiring personal details of the immigrant, comments from magistrates and clergy and a section for her own remarks. With the government refusing to subsidise the survey, the planned 3,000 ‘Voluntary Statements’ became between six and seven hundred. However, the testimonies have proved to be of huge benefit to historians.

Return To England

In 1846 the Chisholms returned to England, and, while her mother looked after the children, now four boys, Caroline and Archibald continued their charitable work. The next several years were productive ones. Caroline successfully fought for wives of ‘Ticket of Leave’ men – convicts parolled to the colonies – to join their husbands, arranged for some children who were left behind when their parents had emigrated some years before, to be reunited with them and gave evidence twice before committees at the House of Lords. The latter were the Committee of Criminal Law and the Committee on Colonization from Ireland, and such was her standing that she was the only female to appear before the House.

The Chisholms travelled around almost every inch of Britain, lecturing or approaching influential people. Caroline contacted relatives of some of those who had given voluntary statements and also attempted to reply to the scores of letters received each day - at one stage averaging two hundred and forty a day – enquiring about emigration. Out of her dealings with these ordinary people, most of whom were unable to fund their own passage, came the Family Colonisation Loan Society. Would-be emigrants contributed towards their fare, the Society paid the balance and on arrival in Australia, agents (based in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney) found them work. They were then able, via the agent, to repay the loan in affordable installments.

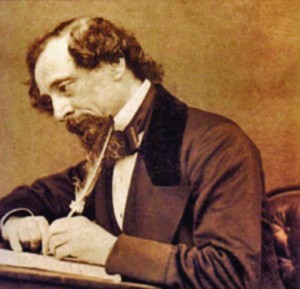

Around this time Caroline met Charles Dickens who was sufficiently impressed with her work to publicise her schemes in various issues of his weekly periodical of Household Words. However, it’s believed he modelled his character Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House – albeit tongue-in-cheek - on her, so perhaps his opinion was a little more complex!

Back To Australia

In April 1854, her work in England done, Caroline and her children joined her husband in Australia, as he had returned there three years before to set up the agencies for the Loan Society. They settled in Melbourne where she she became involved in improving conditions in the goldfields and for families arriving who were looking for work and accommodation. This continued largely unabated until the end of 1857 when health problems – the beginning of what would be ongoing kidney problems – intervened. Although ill health and stringent finances dogged the following years she still managed to hold lectures and open a girls school, Rathbone House, in Newtown where she taught.

Caroline and Archibald’s return to England in 1866 was not intended to be permanent, but once there, her health deteriorated and they were never able to make the return journey. She died on the 25th of March 1877, aged sixty nine and after a Requiem Mass, was buried in Northampton. Her headstone bears the words “The Emigrant’s Friend”. Archibald died that same year on the 17th of August.

By the end of the 19th century, Caroline Chisholm’s remarkable achievements were largely forgotten due to the mass immigration affecting Australia. Not so today, as numerous schools, colleges and organisations named after her, testify. There are growing calls for her to be canonised – perhaps that too, is just a matter of time.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)