The Gospel of Matthew (Part I)

Introduction

Antioch in Syria [modern Antakya in Turkey], third largest city in the ancient Roman Empire, was a Greek-speaking city with a large Jewish community. Around AD 85, a Jewish Christian evangelist composed a Gospel there for a Church that was originally Jewish-Christian, that is, Jews who accepted Jesus as Messiah while continuing to follow Jewish laws and practices.

This evangelist, whom tradition calls Matthew, wrote an anonymous composition. Matthew includes 600 of the earlier published Gospel of Mark’s 660 verses. An eyewitness of Jesus’ ministry, such as the apostle Matthew, would most likely have composed the work fresh from his own memory. We don’t know why the designation “of Matthew” was later attached to this Gospel. It is unlikely that a tax collector from Judea could write the elegant Greek of Matthew’s Gospel. It is possible, however, that some of the material may go back to the preaching of Matthew, who may have ministered in the area of Antioch.

At the time of composition, Matthew’s Church was experiencing two sources of tension.

The first of these was the increasing number of Gentiles joining the community. The question: how can those who don’t observe Jewish purity laws be allowed to eat the meal of the Eucharist together with observant Jewish Christians. Eating together had already become a problem a generation earlier, in the days of Paul and Peter. (See Galatians 2:11-14.) Although believing Gentiles do appear in Matthew’s Gospel (beginning with the Magi), Jesus’ ministry is primarily to the “lost sheep of the house of Israel.” But at the very end of the Gospel (28:19-20) Matthew tells us that the Risen Jesus said, “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.”

The other source of tension was the interaction of Matthew’s Christian Jews with those Jews who were creating Formative Judaism. [Around AD 200, Formative Judaism became Rabbinic Judaism, the forerunner of all modern forms of Judaism.]

In AD 70, the Roman army destroyed Jerusalem and its Temple. Both Christian and non-Christian Jews were struggling to find a new way to live Judaism without the Temple. Matthew’s community held that only Jesus was the authoritative teacher of God’s way. The rabbis relied on the “tradition of the elders.” Both Matthew’s community and those who followed the rabbis thought theirs was the only way for Judaism to survive. We will discuss this second source of tension in later articles.

Chapters 1-2

The Infancy Narrative

Have you ever browsed in a bookstore, pulled out a book that caught your eye and read the first page or two? Experts say that something in those first pages must catch your interest or you are likely to decide not to buy the book. So, why does Matthew begin his Gospel with a long - many people think boring - genealogy? The answer is that to his original readership this genealogy would immediately pique their interest. The first words in Greek are biblos geneseos, an echo of the name of the first book of the bible, Genesis. Already in the first words Matthew reminds us of God’s first creation, leading into the story of how God began a New Creation in Christ.

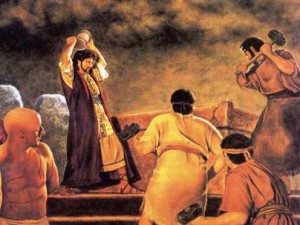

Matthew’s Jewish Christian readers would recognize this genealogy as tracing the lineage of King David. It is Matthew’s way of identifying Jesus as the Davidic Messiah, the hope of Israel. Jesus is also descended from Abraham, father of many nations. Jesus is the hope of the Gentiles as well. Matthew breaks with convention in including four women in the genealogy, and all four are either Gentiles or married to a Gentile. Jesus’ family tree contains Jews and Gentiles, the virtuous (e.g. the reforming King Josiah) and the wicked (e.g., King Manasseh, who practiced human sacrifice), the well-known (the patriarchs and monarchs) but also the obscure (those listed after the Babylonian Exile).

Matthew makes very clear that Jesus was born of Mary, but not Joseph. Like his namesake in the later chapters of Genesis, Joseph receives dreams. In his first dream Joseph is told to take Mary as his wife, since the child is by the Holy Spirit. He is also told to name the child Jesus. Joseph fulfils both commands. The Child is Son of God through conception by the Holy Spirit. He is Son of David by Joseph’s legal adoption.

Note that Matthew does not deny the perpetual virginity of Mary in 1:24-25, “he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son.” Despite the objections of some, the Greek word for “until” does not demand that something happen afterward. Similarly, in English, saying, “I’ll be on vacation until the end of the month,” does not mean that the subject will (at least mentally) be “on vacation” thereafter.

The toddler Jesus was visited by Magi (wise men of a pagan priestly caste, not a royal one) from the East. These Gentiles were able to combine natural wisdom with the light of the Scriptures (presented by Herod’s scribes) to find the new King of the Jews. (By the way, the number three is a guess, probably because they presented three gifts. Matthew does not specify number or names. But ancient paintings depict from two to four wise men.)

The arrival of the Magi set in motion a massive reaction from King Herod, known for his cruelty. While Joseph (once more instructed in a dream) took the Holy Family to Egypt, Herod unleashed a massacre of young boys, trying to kill Jesus. Matthew includes many references to Old Testament passages, explained in a new dramatic way as referring to Jesus.

After the death of Herod, the Holy Family settled in Galilee to avoid the rule of Herod’s equally cruel son Archelaus in Judea. The incidents in chapter two foreshadow the suffering of Jesus in his last days, when chief priests and scribes will combine with another ruler, Pontius Pilate, to put Jesus to death.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)