Saint Margaret Clitherow

When Henry VIII died in 1547 he left a country divided and a sickly son as heir to the throne.Henry’s desperate desire for a male heir had resulted in severing England’s deep Catholic roots and marked the beginning of one of the most turbulent periods in the country’s history.

The Protestant nation he founded continued into his son’s reign, but when Edward VI died at only sixteen years of age, Henry’s eldest daughter Mary, born to his first wife Katherine of Aragon, succeeded to the throne. Unfortunately, Mary’s staunch Catholic faith brought anything but stability to England, as her brief five year reign was filled with bloodshed as heretics paid with their lives for disagreeing with her, usually by being burnt at the stake.

When Mary died in 1558, her sister Elizabeth, daughter of Henry’s second wife Anne Boleyn, became queen. The Elizabethan era saw a return to Protestantism and equally harsh penalties for disobedience with Catholics now on the receiving end.

This was the world Margaret Clitherow grew up in. Born into a Protestant family in York, she was around five years old when Elizabeth took the throne. Her father, Thomas Middleton, had died the year before the accession and her mother had remarried soon after to Henry May, who became a local innkeeper. As taverns were a fertile breeding ground for plots against the monarchy, it would have been part of her stepfather’s role to inform the authorities of anything overheard that endangered the queen. Margaret would have been only too aware throughout her childhood of the fate of those who spoke out of turn.

At the age of eighteen, she married butcher John Clitherow, a widower with two small sons. The family lived in his house – the front room of which was the butchery - in the bustling Shambles in the centre of York. The quaint little street we see today is a far cry from the place of Margaret’s day. More resembling an alley than a street, it was mostly filled with butchers and slaughterhouses with the buildings on either side of the street, so close to each other to be almost touching. The idea was to allow as little sunlight in as possible, as meat was usually displayed on shelves outside the shops and carcasses hung on hooks.

Margaret adapted well to marriage and her surroundings. Also living on the premises were servants and apprentices; by the time she was twenty one years old, she ran a busy household which included two children of her own, Henry and Anne. She was well liked and respected and proved herself more than capable of running the butchery when required.

It was around this time she started to explore Catholicism. Four years earlier strict new laws prohibiting Catholics from attending Mass and generally practising their faith, had been instigated. Disobedience now meant the death penalty and it seems Margaret was impressed with the number of Catholics prepared to die for their beliefs. The death of the Earl of Northumberland Thomas Percy in 1572 particularly influenced her. The popular aristocrat and devout Catholic went to the gallows in York proclaiming that if “he had a thousand lives he would give them up for the Catholic faith.”

Margaret’s questioning eventually led to a meeting with a recusant priest which became her turning point. After much soul searching during which she “found no substance, truth nor Christian comfort in the ministers of the new church, nor in their doctrine” she entered into the Catholic church.

Margaret’s husband was Protestant but came from a predominantly Catholic family including having a brother who was a priest; not only had he no objections to his wife’s change of religion but he supported her decision. However, John Clitherow’s position was tenuous. His high standing in the city through his profession and the Church meant a certain amount of scrutiny, so the less he knew and involved himself in his wife’s affairs the better. Fortunately, there were many husbands in the same situation so the women banded together for support, keeping much from the menfolk.

Over the next few years Margaret continued to defy the authorities over non-attendance of services, which resulted in her spending time in prison, during which it’s believed she gave birth to her third child, William. On her release she immediately arranged, along with some of her neighbours, to have Mass said at her home and give priests any protection needed. While John Clitherow routinely paid her accumulated fines, his wife’s resolve grew stronger.

As Margaret made her plans, a seminary in Douai, France was preparing young – mostly English - men for ordination and a life of subterfuge in England. Throughout the country dedicated Catholics were creating secret passages and rooms within their houses to enable priests to hold Mass there and hide them should the authorities arrive without warning. Margaret also did this; near the top of the house she devised a small room, big enough to celebrate Mass and where, carefully hidden, were stored all the items required for services such as vestments, altar linens and chalices etc. She was emphatic that, should “God’s priests dare venture themselves into my house, I will never refuse them.”

In 1584 Margaret sent her eldest son Henry to France for a Catholic education and the following year arranged for home schooling for her younger children. They, together with the children of one or two of her friends, were taught in another secret room converted in the attic. By this time, she also had a plan B – a rented room elsewhere in York where Mass was held in the event of her own house being raided. As the laws became more stringent, so the risks escalated.

Two years later in March 1586, the inevitable happened. John Clitherow had been called to the Council Headquarters to explain the whereabouts of his son Henry, while back home, his premises was being raided. Margaret, the children and the servants were all questioned and it was one of the schoolchildren, a young Flemish boy, terrified by threats of a beating, who told them where the secret room, housing the chapel, was located. Margaret was arrested and taken to the Headquarters for questioning. When she refused to capitulate, she was thrown into a cell in the Castle prison.

Margaret’s fate had been sealed. She knew that should she plead guilty her family would be forced to testify and this she was determined to avoid. Denying her faith was also out of the question so when asked at her trial how she would plead she answered, “I know of no offence of which I should confess myself guilty.” The penalty for refusing to plead was death by crushing. One of the judges tried desperately to prevent this happening and pressured her to reconsider, but she refused to budge and sentence was passed down.

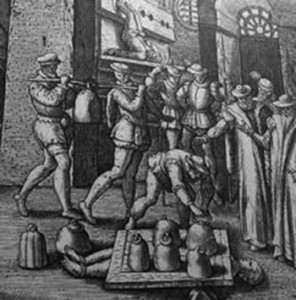

The calmness that Margaret had displayed throughout the trial, remained with her at sentencing. “I will be tried by none but God and your consciences,” she responded. She was then told that she would, “return from whence you came, and there, in the lowest part of the prison, be stripped naked, laid down, your back upon the ground, and as much weight laid upon you as you are able to bear, and so continue three days without meat or drink, except a little barley bread and puddle water, and the third day be pressed to death, your hands and feet tied to posts, and a sharp stone under your back.” “If this judgement be according to your own consciences,” she answered, “I pray God send you better judgement before him. I thankGod heartily for this.”

Margaret spent the next ten days in prison, during which she had several visitors, mainly devout Protestants who tried to ‘convert’ her. One such was the vicar of a nearby town, who asked her how she wished to be saved. “Through Jesus Christ, His bitter passion and death,” she replied. He then asked why she believed in images, ceremonies, sacramentals, sacraments, and such like, and not only in Christ? “I believe as the Catholic Church teacheth me,” she answered, “that there be seven sacraments, and in this faith will I both live and die. As for all the ceremonies, I believe they be ordained to God’s honour and glory, and the setting forth of His glory and service; as for the images, they be but to represent unto us that there were both good and godly men upon earth, which now are glorious in heaven and also to stir up our dull minds to more devotion when we behold them; other than thus I believe not.” Despite his attempts – and many of her friends - she would not be moved so eventually they all gave up. Her husband and children were not allowed to see her so she died without ever setting eyes on them again.

On Friday the 25th of March 1586, Margaret Clitherow was taken to the Tolbooth on Ouse Bridge in York, where a small crowd awaited to witness her execution. Even to the end, she defied the authorities. When asked by a Protestant minister to pray with him, she refused, stating “I will not pray with you, and you shall not pray with me; neither will I say Amen to your prayers, nor shall you to mine.” On kneeling down she prayed for the Catholic Church, the Pope, the Cardinals and all the clergy and for all Christian princes. She added a prayer for the Queen that “God turn her to the Catholic faith, and that after this mortal life she may receive the blessed joys of heaven.” On being told to confess that she died for treason, she answered that she died “for the love of my Lord Jesu.”

She then lay on the floor. A stone was placed under her back, a heavy door laid on top of her and her arms stretched out and tied to two posts. Margaret’s last words were “Jesu! Jesu! Jesu! have mercy on me!” She died 15 minutes later though her body lay there until midnight when it was removed and buried in a city rubbish dump. It took her friends several weeks to find it but when they did, they went to great lengths to keep secret the place where she was given a Catholic burial. Even today it’s not known where Margaret Clitherow was laid to rest.

She would have been proud of her children had she lived. Anne became a nun in Louvain, Thomas died in prison for his faith, William trained in Douai and joined the numerous priests to risk their lives travelling the English countryside celebrating Mass in secret. Henry was never ordained though he did train for the priesthood. He died while still considering which order to join.

Throughout the centuries little was known of this courageous woman. That changed in 1943 when the Catholic Women’s League chose her as their patroness and they began campaigning for her canonisation. It took until 1970 when St Margaret Clitherow became one of the 40 Martyrs of England and Wales. A multitude of CWL members attended the ceremony in Rome to see 27 years of prayers answered.

In 2008, the Bishop of Middlesbrough unveiled a commemorative plaque on Ouse Bridge in York, the place of her death.

Her feast day is March 26th although she is also remembered on August 30th along with fellow martyrs St Anne Line and St Margaret Ward. The feast for the 40 Martyrs is 25th of October.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)