The Coronation Oath

The Royal Marriage - Part II

Of history’s many turning points, the brief reign of Edward VI was a significant one for the Catholic Church. Henry VIII’s son was a frail, nine year old when he inherited not only the Crown but the religious turbulence of his father’s rule. When he died six years later England no longer looked towards Rome for guidance in its Faith; Protestantism in the form of the Church of England was the law of the land.

Over 400 years later this is still so, though now Prince Charles has questioned the Church of England’s right to absolute authority because of its standing in law and would like to see a greater freedom of religions. It sounds simple enough but the Oath he would be required to take upon his accession to the throne is quite definite about where his spiritual loyalties will lie.

The Oath’s origins go back to the year 973, though it’s only over recent centuries that adherence to the laws of the Church of England has formed its basis. It would take a Parliamentary Act to remove a procedure that evolved from that much-married Tudor king five centuries ago.

The Oath’s origins go back to the year 973

Despite Henry VIII’s friction and subsequent breach with Rome, he maintained a staunch Catholic front. He appeared to have no real opposition to the Faith, only the papal administration that came with it. While not openly encouraging Protestantism, behind the scenes he planned a regency council made up of reformers and saw that his son’s tutors were of the same bias.

Awarding himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England enabled Henry to control and dictate England’s religious system. However much his advisers and bishops may have wanted speedier reforms, they were destined to wait until his son became king before they got their wish.

The Council wasted no time in assembling once Edward took the throne. Together with the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer, and Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset, they were a powerful force behind the young monarch. Shortly after Edward’s succession came the first royal injunctions aimed at ridding the Church of superstition and idolatry and getting ‘back to basics’. Statues and paintings were out, while literature compiled by Cranmer and other reformers was in: Hoc est corpus meum became ‘Hocus pocus’ – superstitious nonsense

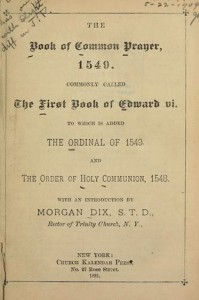

In 1549 came the first Book of Common Prayer which was a prelude to the first Act of Uniformity which compelled clergy to use the new book or face imprisonment. Further legislation allowing priests to marry followed hard on its heels. But for some, the changes didn’t go far enough and towards the end of that same year an uprising took place. Radicals led by the Duke of Northumberland took over, deposing Somerset who was thrown into the Tower. Cranmer came through unscathed as his views were increasingly heading towards a stronger Protestant England.

A new Prayer Book preceded the second Act of Uniformity in 1552. The liturgical changes went further than ever as now the European influence of the Reformation was being seen. Churches were being stripped of more of their assets and ancient rites of worship ceased or were drastically altered. Then, just as England was firmly in the grip of Protestantism Edward VI died

When Henry VIII’s long suffering daughter Mary came to the throne, she was a bitter, lonely woman of thirty seven who had spent twenty years previously as a virtual outcast. Henry’s claim of her illegitimacy had forced Mary and her mother Catherine of Aragon to live, humiliated and disgraced, in seclusion. Her staunch Catholic Faith had kept her going but unfortunately by the time she became Queen this had turned to fanaticism.

Mary’s first act was to repeal all of Edward’s legislation. As many of Edward’s supporters went into hiding or were imprisoned, a new regime got underway. Churches were restored to their original conditions, bishops who had lost their sees over the previous six years regained them and plans to reconcile with Rome were set in motion. But it couldn’t work. Too many changes had occurred since the death of Henry VIII for the people to be easily swayed, so when persuasion failed persecution began.

People from all walks of life were burned at the stake for their beliefs. Thomas Cranmer battled with his conscience for some time; his Faith was strong but he abhorred the thought of disloyalty to the Sovereign. In choosing he paid with his life.

When Mary died in November 1558 she left an angry and embittered nation, only too ready for the stability it was hoped her half sister Elizabeth would bring to the monarchy and Church. Anne Boleyn’s 25 year old daughter took action almost immediately. At Parliament’s first sitting in January 1559 two new Acts were passed: Supremacy and Uniformity. Elizabeth became Supreme Governor of the State and Church choosing not to reinstate the Supreme Head title dropped by Mary.

The Uniformity Act incorporated the 1552 Prayer Book. Interestingly, this was chosen over the 1549 edition which Elizabeth preferred, because of its Protestant pressure on Parliament. Its rules were more stringent and this together with some further injunctions left people in no doubt that the reforms were back for good; conflict with Rome was about to be reawakened.

Catholics were tolerated at the beginning and the transition from Mary’s reign to Elizabeth’s went smoothly. However, a papal bull issued in 1570 excommunicating Elizabeth sealed the fate of English Catholics – their loyalties could no longer be divided, it was the Pope or the State. England had finally severed its ties with Rome and for those who refused to renounce their faith the penalty was death.

Throughout the Elizabethan era religious strife continued. The Puritans were on one side, their Presbyterian influence demanding a more fundamental approach and the Catholics were on the other wanting a return to papal rule. The Protestants stood in the middle refusing to give any ground.

Further laws were passed in 1604 under James I which strengthened the Church’s position. But it was the reign of Charles I that saw the last major upheaval in the battle of the Faiths. Charles’ fixation with the Divine Right of Kings – that kings were answerable to no one – led to Civil War and ultimately to his execution. During the Commonwealth years that followed many independent religious bodies, such as Congregationalists and Baptists, sprang up.

So, Prince Charles should have no problem with The Accession Declaration, he’s merely affirming his Faith. But what of his duties, as a Protestant, to his country and his subjects?

No real persecution took place under Cromwell’s Puritan rule, but Protestants were anxious to see the Church re-established. The only answer was in the restoration of the monarchy which occurred two years after Cromwell’s death. Charles II immediately began repairing the damage done during his father’s reign and in 1662 a new Prayer Book was issued prior to another Uniformity Act. The Church of England was once again law.

While a certain amount of spiritual disharmony remained during the Restoration, in the main it was a very Protestant England, so on Charles’ death his Catholic brother James was not warmly welcomed. Unfortunately, James hardly had time to get used to his royal title when he was ousted – too many people were afraid of a repetition of Mary Tudor’s reign.

When William and Mary jointly took the throne in 1689, a Bill of Rights was passed which not only gave Parliament political supremacy but ensured that England would never again be ruled by a Roman Catholic. Furthermore the Coronation Oath was revamped to safeguard the ‘Protestant Religion Established by Law’.

In 1706, Parliament under Queen Anne decreed that ‘the said true Protestant Religion and the Worship, Discipline and Government of this Church(would) continue without any Alteration to the People of this Land in all succeeding Generations.’

With the Church of England permanently established it was 200 years before any other changes were made. George V in 1910 objected to the wording in the Accession Declaration used since Queen Anne’s reign, which denied the existence of transubstantiation in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. He was also offended by references to invocations to the Virgin Mary and the sacrifice of the Mass as being superstitious and idolatrous. Despite some strong opposition the King succeeded in having all the above deleted and replaced by a more straightforward Declaration: ‘I (name) do solemnly and sincerely in the presence of God profess, testify and declare that I am a faithful Protestant, and that I will, according to the true intent of the enactments which secure the Protestant succession to the Throne of the Realm, uphold and maintain the said enactments to the best of my powers according to the law.’ Each monarch since then, including our current Queen has used that Declaration.

So, Prince Charles should have no problem with that – he’s merely affirming his faith. But what of his duties, as a Protestant, to his country and his subjects? That’s where the Coronation Oath comes in. During the crowning ceremony the monarch, after agreeing to take the oath and promising to govern his or her people at home and abroad is asked: ‘Will you to the utmost of your power maintain the Laws of God and the true profession of the Gospel? Will you to the utmost of your power maintain in the United Kingdom the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law? Will you maintain and preserve inviolably the settlement of the Church of England, and the doctrine, worship, discipline, and government thereof, as by law established in England? And will you preserve unto the Bishops and Clergy in England, and to the Churches there committed to their charge, all such rights and privileges, as by law do or shall appertain to them or any of them?’

If the Prince goes ahead with his plans to change, his title, history – along with the above Oath – will be rewritten.

Entries(RSS)

Entries(RSS)